Out in the field traversing rugged rocky slopes or in the research lab analysing data, no day is the same for Maggie Nichols, a predator ecologist with a mission to rid Aotearoa of stoats.

Hooked from the start

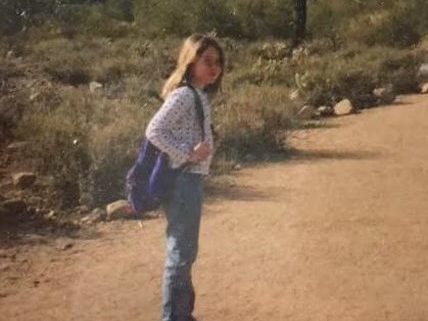

Forget Nintendo 64 or rollerblades, Maggie Nichols asked for a camera trap for her tenth birthday. Studying the foxes and coyotes on her family farm in the US set the foundations for her career as a predator ecologist.

Her fascination with carnivores led to a PhD on feral cat monitoring using trail cameras, and in 2017 she joined Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) as a predator ecologist. Now, she’s sinking her teeth into the problem of eliminating stoats from her adopted home of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Maggie works in areas where ZIP aims to eliminate all invasive predators and defend from re-incursion, primarily South Westland.

Once aerial 1080 drops have suppressed predator numbers, Maggie and her colleagues head in, trying to find the best way to target and eliminate the survivors.

This involves researching animal behaviour, testing different kinds of tools – like traps, cameras and toxins – and finding out what works and what needs improvement.

A not-so-typical day

When she’s not working from ZIP’s research laboratory at Lincoln University near Christchurch, Maggie can be found in the field, traversing the wild and rocky slopes of the Perth Valley in South Westland, with a radio in hand.

“You’ve gotta get out in the field – you can’t be useful to people on the ground unless you’re working with them and understand the challenges they’re facing.

“We’re constantly cross-pollinating, seeing how a device or method works and trying to develop it.”

When visiting South Westland, Maggie works out of ZIP’s field base – a motel on the outskirts of Franz Joseph, near the Perth Valley.

“It’s pretty busy and fun at the field base, there’s a lot of people and a lot of movement.”

“We all pile into the van and drive to the road end where we get to our project field sites, and take a helicopter flight into the backcountry.”

Sometimes it might be a multi-day trip – there are huts and bivvies to stay in, and researchers will work out of these spots, getting collected by helicopter when it’s time to head back to base.

“You’re working in this absolutely pristine place and hearing radio chatter about what people are finding out in the field,” Maggie says.

Mapping software is linked to data capturing software on her phone so that at the end of a trip, back at basecamp, Maggie can see where she’s been and what she’s found.

Many researchers will have been out collecting trail camera footage, and the SD cards they’ve collected from the cameras get reviewed by smart tech software, which can help them flick through images quickly to classify them.

The footage is synced to a database and flashes up on a map, “we can instantly see where animals are being detected and make a bit of a plan for what to do next,” Maggie says.

“We’re also looking for native species too – everyone gets really excited if we see native species or something unusual.”

Getting the word out

Back at her desk, Maggie analyses the data, researches animal behaviour and writes up her studies to help others in the field.

She recently published a paper, together with her colleagues Jennifer Dent and Alexandra Edwards, about how the team successfully used toxin-laced dead rodents to bait the elusive last-remaining stoat population.

Looking to the future

Since the success of the Perth Valley project and ongoing management work from ZIP, kea and other native bird populations are flourishing.

“One of the coolest changes has been species like kākāriki – which you’d only hear occasionally when we started our work – and now you see them foraging on the forest floor; it’s a sign they’re comfortable and feel safe.”

As Aotearoa New Zealand inches closer to predator free by 2050, Maggie says there are reasons for hope.

“I have no doubt there will be a lot of twists and turns along the way, but I think the really fun thing about it is that we’re on track, and we’re showing that it’s possible,” she says.

“Ecosystems can heal themselves really fast, but to see big change, we’ve got to remove those predators.”