Imagine lush landscapes alive with Aotearoa New Zealand’s quirky and unique plants and wildlife. This is the Predator Free 2050 vision but to get there we need new tools. While 1080 operations and trapping networks remove most introduced predators from an area, getting the remaining animals is a challenge. The last stoats can be particularly elusive as they avoid traps and toxins.

But what if the bait was disguised as a rat? Researchers at Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) believed that toxin-laced dead rodents might be an effective tool to target remaining stoats and stop them reinvading a predator free area.

Toxic rodents keep it real for stoats

Maggie Nichols has worked for ZIP since 2017. She spends her days researching the best ways to protect native species by eliminating introduced predators. Keen to find an innovative solution to the stoat problem, Maggie and her colleagues Jennifer Dent and Alexandra Edwards (also from ZIP) believed toxin-laced dead rodents could be the solution.

They’ve published their research in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology. We caught up with Maggie to hear about the project and this exciting new tool.

“If you’re just looking to knock numbers down, bait stations and trapping are great – you’ll probably get 50-80% of the population. But if you’re looking for those last stoats that will just simply never interact with a man-made structure, you’re going to need to go for something as simple and natural as possible,” Maggie says.

They knew from previous 1080 operations that while stoats don’t often eat baits themselves, they do hunt and eat rats and mice that have. Rodents are one of the preferred prey of stoats anyway, so it made sense to use them as baits. As Maggie says, “It’s something they will actually find in their environment.”

The toxic rodents are designed to be used alongside other techniques. “It’s a mop up tool in an area where you’ve already eliminated predators and you’re getting some ongoing incursion,” she says.

To trial their research, the ZIP team needed an area on the mainland that was almost predator-free but vulnerable to reinvasion.

Protecting the Perth

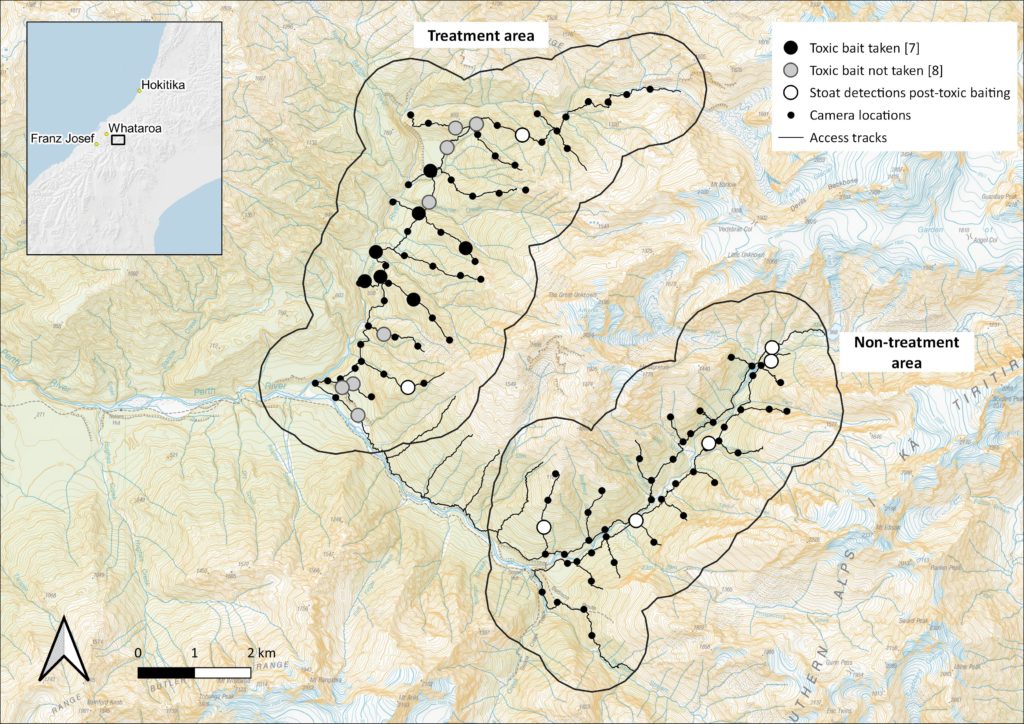

The Perth River Valley in South Westland was the perfect site for this research. Covering 12,000 hectares, the rugged peaks and lush native bush of the valley are home to numerous native species, such as kea, whio and tuke (rock wren) as well as flowering trees like southern rata. The site sits within the wider footprint of the Predator Free South Westland project, which seeks to eliminate possums, rats and stoats from 100,000 hectares by 2026.

What’s more, it was almost totally free of introduced predators. In 2019, ZIP and local partners had wiped out almost all possums, rats and stoats from the remote and rugged valley. The Perth Valley Project was the first attempt at total elimination on the mainland and a huge win for conservation.

Once most of the introduced predators were gone, the land could largely protect itself from reinvasion – the steep, jagged mountains and swift, cold rivers are powerful natural barriers. But while rivers and mountains can prevent rats and possums, stoats are strong swimmers.

In November of 2019, as they bred and began looking for new homes, the stoats started creeping back in.

“It was disappointing but it was also what we expected. We had never expected to permanently eliminate stoats with that one phase,” says Maggie.

Instead of letting it discourage them, the ZIP team saw this as the perfect chance to trial the use of toxin-laced dead rodents to remove those stoats.

Stoat selfies and rodent-filled backpacks

As part of the Perth Valley Project, ZIP had installed around 143 cameras up and down the valley. The cameras lured introduced predators with egg mayonnaise dispensed from ZIP MotoLures and snapped thousands of photos.

Thanks to the stoat selfies, they had a clear picture of where the stoat hotspots were. To make sure the stoats would come back to the cameras when they laid the toxic rodents, the sites were continuously pre-fed with the mayonnaise.

Then, after transporting frozen toxin-laced rodents to South Westland, ZIP field rangers loaded up their backpacks with carefully sealed bags of frozen rodents and headed into the valley.

“We simply place them next to the MotoLure that has the mayonnaise they’ve been eating and the camera records the stoats coming. It also records if any other species shows up and helps us gather a lot of data on the efficacy and risks of this method,” Maggie says.

Maggie joins in on a lot of this fieldwork, heading over to the Coast as often as she can. The local rangers have even given her the joke title of “spare field ranger” because she’s there so often, helping out wherever she’s needed.

Zero, zip, zilch!

The research was hugely successful. They found 94% of the stoats in the areas they targeted were eliminated by consuming a toxic rodent within a week of deployment. It’s a fantastic result and a promising new tool for the predator free vision.

It’s innovation and research like this that will get us past suppression and into elimination.

“Innovation doesn’t happen because you know the outcome and you know how to do it. The point of innovating is to find new technologies to help us become more efficient and more effective.

“With tools like this we are protecting the Perth Valley and, eventually, all of that southwest footprint in perpetuity,” Maggie says.