ON THIS PAGE

How did they get here?

Along with ferrets and weasels, stoats were introduced in the late 1800s to control the rabbit population. Warnings from New Zealand scientists, including ornithologist Walter Buller, were ignored and the introduced stoats quickly began to wreak havoc on native bird populations. (For more information on the introduction of stoats, including 19th century newspaper coverage, see ‘Liberation of stoats and weasels’.) Until 1936, they were even protected by law, along with ferrets and weasels, because of their rabbit-controlling abilities.

What do stoats look like?

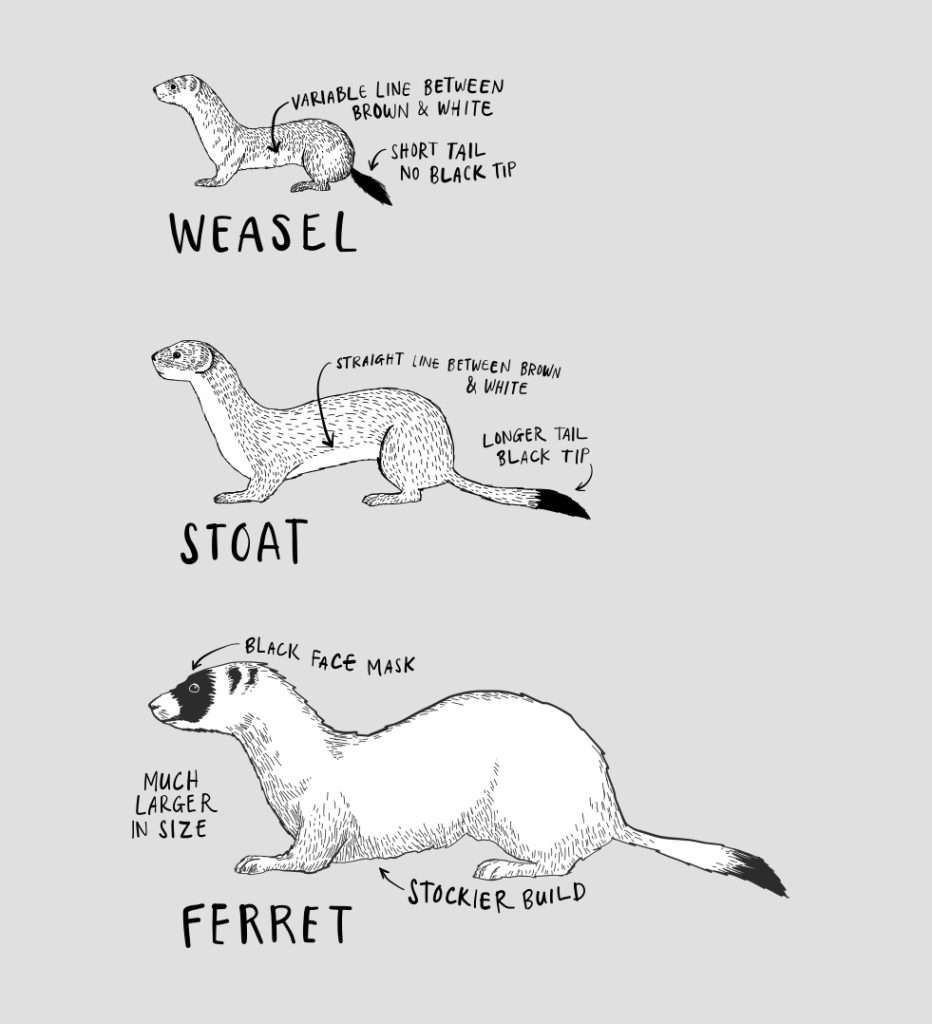

Stoats belong to the same mustelid family as weasels and ferrets. They’re bigger than weasels and smaller than ferrets, and they have a bushy tail with a black tip. They also have a black/brown coat and a pale belly and throat.

Where do they live?

Stoats are spread across Aotearoa and live anywhere they can find prey – in high country, in beach areas, on farms, in bushland and forests. They even live in high altitudes above the tree line.

What do we know about stoat behaviour?

Like other mustelids, stoats have very good eyesight, good hearing and a strong sense of smell. They hunt day and night, can move quickly, and are good at climbing trees to eat baby birds and eggs in the nest. Stoats check every burrow and hollow they see and if they find a ground-nesting bird it has very little chance to escape.

If they get the chance, they’ll kill more than they need for food and hide the rest in their den to eat later. They can kill animals much bigger than themselves and have well-concealed den sites.

Stoats can travel long distances very quickly – one young stoat traveled 70 km in just two weeks. They are also strong swimmers and can swim 1km or more to reach islands. Stoats are clever and careful; they are very suspicious of baits and traps so it is difficult to control them.

What impact do they have?

DOC describes stoats as ‘public enemy number one’ for Aotearoa’s native birds. They are relentless hunters and have a significant effect on species such as wrybills, the New Zealand dotterel, black-fronted terns and young kiwi. Only about 5% of Northland’s brown kiwi chicks reach adulthood, and according to DOC their biggest threats are predation from stoats and feral cats.

Birds that nest in holes in tree trunks such as mohua, kākā and yellow-crowned kākāriki are also vulnerable to stoats.

While their main prey are rats, mice, birds, rabbits, hares, possums and insects (particularly wētā), stoats will also eat lizards, freshwater crayfish, roadkill, hedgehogs and fish.

Another major challenge with stoats is their rapid breeding. A mother stoat can have up to 12 kits at a time, but usually has 4-6 babies. A female stoat can get pregnant when she is still a blind, deaf, toothless and naked baby – at only 2-3 weeks old. Even though she is pregnant, her kits won’t grow inside her until she is an adult. They will be born the following spring.

How you can help control stoats

The most effective way to manage stoats is by regular and ongoing trapping.

- Buy an animal welfare approved stoat trap from our shop, such as the DOC 200, the DOC 250 from one of our key suppliers or the Smart Trap from Goodnature. Place traps along fencelines, hedges, stream banks, fallen logs or tree roots. Keep entrances clear of weeds or fallen leaves.

- Use eggs or fresh meat as lures. (Salted meat is better during summer months.) If you have cats, use eggs as bait and avoid meat.

- Check the trap at least once a month and change the bait.

- Make sure you always wear gloves when handling your trap or catches.

View our trapping and baiting toolkit to ensure you get the best results and download our quick trapping guide for stoats (PDF, 136KB).