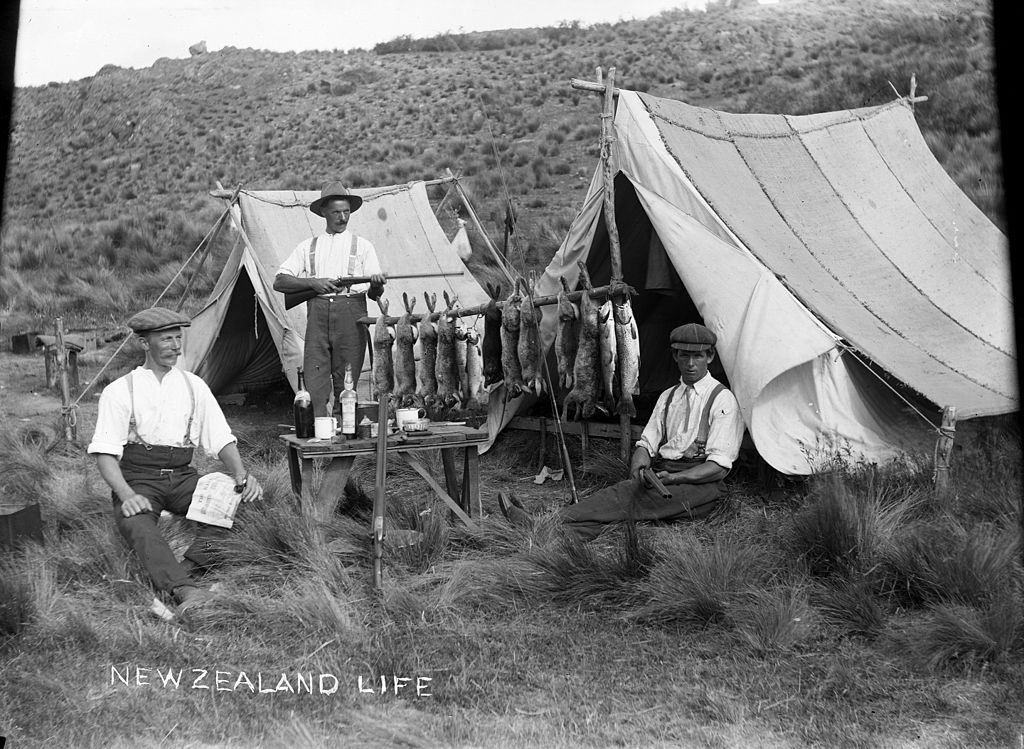

Why did they do it? What possessed New Zealand’s government of the day, its citizens and acclimatisation societies to introduce rabbits and then stoats?

It’s easy to judge in hindsight. But perhaps we should do more than judge. A better understanding of what they were thinking at the time might help stop us making similar 21st Century mistakes today. So why not take a trip back in time…

A large number of early New Zealand newspapers have been digitized and can now be searched and read online through the National Library’s ‘Papers Past’ website. Various archives throughout New Zealand also hold records of government departments and acclimatisation societies, along with the farm diaries and personal letters of individuals involved in the various introductions that were carried out across New Zealand. Professor Carolyn King has researched these sources extensively and recounts her findings in an article just published in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology.

“The flavour of the debates and the assumptions that led to the commissioning of private and government shipments of these animals are best appreciated from the original documents. I describe the sites of the early deliberate releases in Otago, Canterbury, Marlborough, and Wairarapa, and list contemporary observations of the subsequent dispersal of the released animals to named locations in Southland, Westland, Wellington, Hawke’s Bay, Auckland and Northland.”

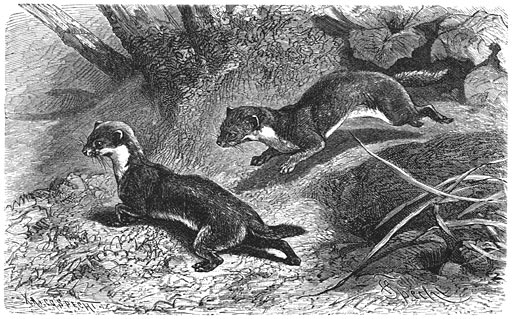

The introduction of stoats and weasels followed on from earlier introductions of rabbits – which had progressed rather too successfully. The problem could be solved, it was thought, by reacquainting the ever-spreading rabbits with their natural predators. Initially weasels were introduced in greater numbers than stoats, but ultimately it is the stoats that have become more widespread.

“Much as we may be, rightly, wary of newspaper journalism, the late nineteenth century newspapers were well developed and highly valued as the only source of public information, both local and international, and their reports were often very detailed and comprehensive. Consequently, historic news items are worth careful scrutiny, because those written by eye-witnesses, especially if citing reputable authorities or government officials, often recorded valuable contemporary observations of the natural world, illustrating how people thought and behaved in the past.”

Settlers were, at the time, more concerned about the effect stoats and weasels would have on their sporting activities – shooting game birds – than on the impact on native birdlife. They also genuinely believed that introducing predators would be sufficient to control rabbits.

“An appropriate introduction to this paper is provided by an extract from a report written in 1898 by Mr Reginald Foster, a former Chief Stock Inspector for Canterbury, and reprinted in the Matura Ensign (1898):

Tame, hutch-bred rabbits were liberated by the early settlers in many parts of the colony, and, owing to the absence of indigenous natural enemies, they soon established themselves, but it was not until the wild rabbit was introduced in Southland in 1852, and the equally wild silver grey at Kaikoura by Capt. Keene about the same year, that their increase became noticeable…the danger was not realised until the rabbit commenced to spread northwards like a tidal wave, causing inevitable ruin in their progress…[so] Government introduced stoats and weasels for liberation on the Crown lands…although I, in common with all sportsmen, regret their introduction, I am satisfied that they are, and will continue to be, the main factor in keeping the rabbit pest under [control] on the higher lands in the colony where it is impossible to deal with them effectively by any of the known means of rabbit destruction.”

Initially ferrets were imported. Being semi-domesticated, ferrets were easy to obtain and breed, but were also vulnerable to canine distemper and cold, wet weather.

“Government and private imports of stoats and weasels – ‘the natural enemy’ from England – were seen to be the only way to curb the rabbit menace in the high country where ferrets were regarded as too ‘delicate’, so as soon as each shipment arrived, stoats and weasels were transported to the worst-affected runs.”

Initially the new arrivals were highly valued – at least by some members of officialdom.

“The Government’s Chief Rabbit Inspector, Benjamin Bayly (appointed in 1881), tightened up the previous rabbit-control legislation and organised the shipments of stoats and weasels. In the hope of conserving every possible weapon against rabbits, the new Act placed all natural enemies of the rabbits under legal protection. Anyone could be fined up to £10 for killing a ferret, stoat, weasel or cat, even in areas where there were no rabbits.”

Not everyone was happy, however – particularly when their poultry started disappearing.

“Accelerating outrage and complaints from the settlers, that this illogical provision prevented them from destroying predators to protect their cherished poultry and introduced game birds, produced only a terse official notice from John McKenzie, Minister for Agriculture (New Zealand Gazette 1894), as reported by the Otago Witness (1894):

‘Attention is drawn to the Provisions of “The Rabbit Nuisance Act 1882” for the protection of the natural enemy of the rabbit, and it is hereby notified that the animals mentioned hereunder have been Protected, as provided for in Section 29 of the abovementioned Act: ferrets, cats, stoats, weasles, mongoose’.

“The only legal remedy then available was to remove the offending predators alive to somewhere they would be more welcome.”

In spite of protests, the liberations continued.

“At least 7838 stoats and weasels were landed in New Zealand over the decade 1883–92, in at least 25 organised shipments. The new arrivals were liberated only on the worst rabbit-infested pastures, but both species spread rapidly, reaching most parts of the North and South Islands within 20–30 years.”

Professor King reproduces accounts from regions throughout New Zealand as mustelids were gradually introduced. In Otago, for example, the mustelids had a rough voyage out, but quickly made themselves at home.

“The first trial shipment of 25 stoats and weasels (plus 8–10 ferrets) was loaded onto the sailing ship Waitangi in December 1882, in the care of an experienced gamekeeper from Lincolnshire, Walter Allbones. All but ten of the animals were lost overboard during a storm (Otago Daily Times 1883); the survivors were released at Bushey or Bushy Park (sources use either name), an estate near Palmerston. Within a few hours one of the ten (unidentified) had travelled several miles distant from where it was set free, where it destroyed seven ducks (Otago Daily Times 1884).”

Other notable Otago runholders of the day were keen to get their share of the new arrivals.

“Hon. Robert Campbell managed to score seven stoats and 25 weasels for his Benmore run via his Dunedin agent, A. C. Begg. The archives of the New Zealand Loan & Mercantile Agency Co, Ltd in Dunedin include an entry ‘3 February 1885 ‘To stoats and weasels £90-05-00: Robert Campbell & Sons, Ltd. A.C. Begg, Dunedin’. Campbell’s manager Thomas Middleton reported to him, on 13 February 1885, that he had turned them out ‘where rabbits bolted under rocks, and they started work at once. We could hear the rabbits singing out. While we were watching them, a young weka rushed out from under a rock with a weasel hanging on, but it fell off with a mouthful of feathers’. Ten days later, in a letter to John Wilson, Campbell’s agent in London, Middleton marvelled that ‘The little things seemed none the worse for their journey, but ran away and disappeared at once among the rocks – going for the rabbits and wekas minutes afterwards’. He added on 21 March that he ‘visited the weasel locality, no rabbits to be seen’.”

The supply of stoats and weasels couldn’t keep up with demand.

“Not everyone got as many animals as they wanted, or even any at all: (Government Chief Rabbit Inspector) Bayly told the disgruntled landowners that ‘there were so many applications that if I had had ten times the number I could have disposed of them’.”

Not surprisingly, the imports did well. There was no shortage of prey – in fact they were spoiled for choice.

“By 1892, Blair Fullerton, the Rabbit Inspector based in Oamaru, found that ‘Weasels are spreading throughout the Clutha…and evidently are increasing rapidly’. He added that it would be some time before they would be numerous enough to keep down the rabbit pest, as they have mice, rats, and birds to eat as well as rabbits.”

Professor King’s account continues with details of the introductions to other regions. It’s a fascinating read. But as the wisdom of hindsight tells us – these tough, cunning, successful predators never did get on top of rabbit numbers. They have, however, made themselves very much at home.

This article is published in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology and is freely available online.