Approximately one-third of New Zealand’s islands are now free of all invasive mammals. Could Auckland Island be next?

Predator control and eradication operations are often carried out in winter – when predators are hungry and uptake of bait likely to be greater. But when it comes to eradications of sub-Antarctic islands, like Auckland Island, the winter weather can get pretty severe, meaning there may only be a short ‘window of opportunity’ when conditions allow aerial bait drops to occur.

The larger the island, the longer it takes to complete a bait drop over the whole area – meaning there’s more chance that the weather will close in before the operation is complete. Add to that, a tiny target animal with a very small home range and its easy to see why a future mammal eradication on Auckland Island that includes mice, as well as pigs and cats, is described as ‘logistically challenging’.

So could a summer eradication succeed?

Earlier this year, James Russell, Richard Griffiths, William Bannister, Mark Le Lievre, Finlay Cox and Stephen Horn carried out trials on Falla Peninsula on the Auckland Islands to test summer eradication feasibility.

“The aim of this study was to examine the feasibility of using a low sowing rate on Auckland Island and applying this during the summer, when there are longer daylight hours and more settled weather, and thus an increased opportunity for helicopter operations to be completed in one season. Auckland Island is the last of the New Zealand subantarctic islands to have introduced mammals, including pigs, cats and mice, and its large size makes mouse eradication logistically challenging. Therefore, it has been suggested that a lower bait sowing rate than is typically used for island rodent eradications should be applied and that eradication should be undertaken during summer, despite this being the rodent breeding season and alternative food being more readily available.”

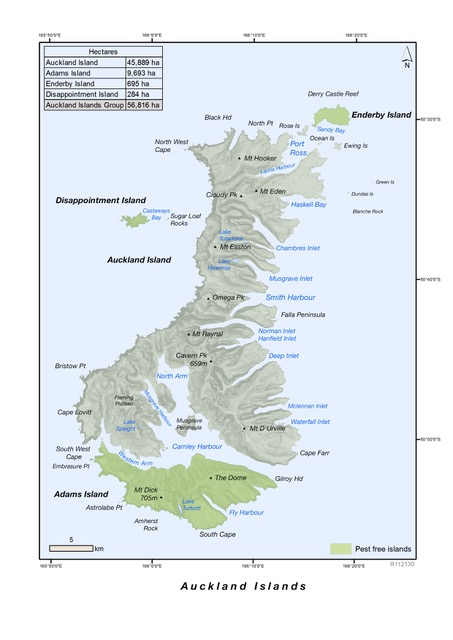

New Zealand’s sub-Antarctic islands are a UNESCO World Heritage Site with Auckland Island having a total area of 46 000 hectares. Pigs, cats and mice have been present on the main island since 1806, when it was discovered by Europeans and they’ve had a devastating impact on island plants and wildlife.

Falla Peninsula was chosen as the study site as it was relatively easy to isolate the test area and remove any pigs and cats present, which might have interfered with the mouse evaluation.

“This study was carried out on Falla Peninsula on the east coast of Auckland Island. The 951-hectare peninsula has an elevation of 284 metres and narrows to a 258-metre-wide bottleneck from coast to coast, making it a suitable setting for minimising the risk of mouse immigration, which was important as previous bait uptake studies have been unable to rule this out as a potential factor explaining the lack of bait uptake by some individuals. It was also necessary to remove all pigs from the peninsula, as a single pig could have consumed enough bait to prevent one or more mice from being exposed. Therefore, this was achieved by erecting a temporary electric fence across the narrowest point of the peninsula to discourage and indicate reinvasion and then undertaking aerial hunting aided by a thermal imaging camera and a team of six ground hunters with dogs in January 2019.”

In February 2019 non-toxic bait containing a fluorescent dye (pyranine, visible with a UV torch) was applied across the Falla Peninsula at a rate of 4 kg per hectare. The researchers also trapped mice for 7 days using 13 live and kill trapping grids to determine their population status, density, home range size and bait uptake. Bait availability was concurrently monitored along 30 transects.

“On the main islands of New Zealand, animal control operations with 1080 have moved towards using the lowest possible sowing rate to achieve biodiversity or disease management outcomes. However, managers generally opt to use higher sowing rates for eradications with brodifacoum on islands to minimise the risk of eradication failure.”

“DOC’s current agreed best practice for the eradication of mice on islands is two applications of cereal bait containing brodifacoum at a rate of 8 kg/ha, which would pose significant logistical challenges for the proposed eradication of mice from Auckland Island due to the large amount of bait that would need to be transported and applied by aerial delivery within the available weather windows to ensure its exposure to every single mouse. However, rodent eradications on islands near to Auckland Island have previously been achieved using lower sowing rates. Furthermore, previous studies on Auckland Island have revealed that the population density of mice is generally low with associated low capture rates. Therefore, it is possible that mice could be eradicated from Auckland Island using a low bait sowing rate.”

Mice were initially neophobic towards the trapping devices and thereafter were captured at low rates across both trap types.

“Tracking cards in tunnels recorded 0% tracking when they were run on the same day as installation in December but > 85% when tracking was repeated using the same tunnels in January and February.”

This eradication treatment was simulated using a single application of nontoxic Pestoff™ 20R cereal pellets containing pyranine dye (0.2%).

“The pellets were aerially applied in fine weather along flight lines that were 45 m apart to achieve a 50% overlap of 90-m baiting swaths across the whole of Falla Peninsula. Bait application was completed on 6 February 2019 over a period of 8 hours, which included calibration of the low sowing rate.”

“The kill trapping grids were opened 2 days following bait delivery and trapping was undertaken for the following 7 nights (i.e. on nights 3–9 following bait delivery) across all kill trapping grids, as well as on the second tussock live trapping grid on Falla Peninsula. All mice that were captured on these grids were considered to have been exposed to the bait application.”

During the trapping period, a total of 274 individual mice were captured – 42 in the live trapping grids (24 of which were necropsied but excluded from further analysis) and 232 in the kill trapping grids (all of which were necropsied).

“Trapping rates in the kill traps increased across the 7 days of trapping from 24 mice on the first 2 nights to 42 on the last night (with 441 trap nights per night). Of the 244 mice that were trapped in the bait treatment area (kill trapping grids + second tussock live trapping grid), only two individuals (< 0.1%) had an absence of pyranine indicating that they had not consumed bait. Both of these mice were very small juveniles (< 10 g) and were captured in the tussock habitat on nights 4 and 9 following bait application.”

Because these two mice were juveniles, the researchers believe they would have been vulnerable to a second application of bait approximately 4 weeks later, once they were mature.

“Although we did not undertake a second bait application in the present trial because it is generally precluded in bait uptake studied where lethal sampling is necessary, we suspect that a second round of bait application at a sufficient interval after the first (e.g. 4 weeks) would allow any very young mice that were not exposed to bait during the first application to mature such that they would consume bait following the second application. Furthermore, this 4-week period should still be soon enough after the first application to avoid the complications of increased food resources that can occur when there are eradication survivors and to prevent those juveniles that survived from breeding themselves.”

“At the time of this trial, the mice on Auckland Island were in the middle of their summer breeding period. Although the densities of mice varied greatly across our trapping grids, they could be considered high for Auckland Island, especially when compared with trapping efforts that were carried out in autumn 2015. This is likely due to the present trial corresponding with a tussock masting event, which only occurs every 4–5 years on average and was one of the strongest in decades.”

The mice on Auckland Island appeared to be highly wary of new devices.

“Tracking tunnels that were installed and run on the same day in December, which is contrary to best practice, did not detect any mice but subsequently tracked much higher rates later in the season. Therefore, this may partially explain why the kill trapping grids that were installed prior to being set had relatively and consistently higher trapping rates than the live trapping grids, which were also opened on the same day as installation.”

So could a summer eradication at low sowing rates succeed? Overall, the researchers conclude that more evaluation is needed.

“Our findings also suggest that we require a greater understanding of the population biology of rodents if we intend to eradicate them when they are reproductively active. This has not previously been an issue for mouse eradications, which are typically carried out in winter, but is increasingly being recognised as a research issue for eradications in the tropics, where rodents breed all year round.”

The full research report has been published by the Department of Conservation as part of its Research and Development Series and is freely available online.

Mouse bait uptake and availability trials on Falla Peninsula, Auckland Island (2019)