Four months on from the first boat leaving for Auckland Island, all the field teams are home safely for the winter. A whirlwind summer has seen great gains in knowledge about the island and has given valuable insights into how the ambitious plan to remove pigs, cats and mice might work.

Field trials to inform the feasibility assessment for the three proposed eradication programmes were carried out at two main sites on the island. Falla Peninsula was used to test the proposed pig and mice methods and Deas Head in the north of the island was home to a large-scale cat detection trial.

Pigs

Following the establishment of a temporary electric fence across the isthmus, Falla Peninsula became a small scale model of Auckland Island to trial the removal of all pigs. Pigs need to be removed before a mouse eradication is attempted as they create ‘holes’ by scoffing up bait, reducing the likely of each mouse being able to access bait. Trail cameras were set up on the fence line, so although it was not 100% pig proof, the team could monitor any pigs entering or exiting the trial area.

The pig phase of the project involved two teams; one in the sky and one on the ground. The aerial team arrived first and tested the use of high definition thermal imaging camera to guide aerial hunting to great effect. The technique could reliably detect pigs in the tussock and one occasion the team identified a small kitten in the scrub. The coastal rata forest proved more challenging but pigs and sealions could still be identified on a close approach.

The ground hunting team then arrived in early January to carry out the mop-up phase of the pig removal. After a lumpy voyage ten dogs and five hunters swept across the 930ha peninsula twice in tight formation to remove any animals missed by the helicopter and the one pig that made it through the fence.

The steep terrain and bluffs on the peninsula meant the hunters with dogs had to adopt a sidling pattern of movement rather than the traditional top-to-bottom movement proven to be 100% effective elsewhere. The band of tight coastal scrub also forced them to spend a large amount of time crawling on their hands and knees – the stories of scrub so tight you can walk on it proving to be true, with movement slowed to 100m an hour in some areas.

Mice

After two full sweeps of the peninsula by the hunters all pigs had been removed from the area, proving that this combination of aerial and ground hunting can be used with great effectiveness on Auckland Island, despite the challenges posed by the steep terrain, the tight vegetation and the ever changing weather!

After the departure of the pig team and their dogs from Falla Peninsula, the mouse team arrived to test out two proposed variations to standard mouse eradication best practice: a low bait sowing rate and carrying out the operation in summer. If successful, these methods would make carrying out an eradication on such a large scale in such a challenging environment logistically feasible.

Five tonnes of non-toxic bait containing a biotracer was spread on Falla Peninsula, now clear of pigs, at a rate of 4kg per hectare – half that usually used in an eradication. After allowing the mice a few nights to scoff this unexpected gift from the sky, a grid of snap traps and live-capture traps was set up to work out if every mouse had consumed bait. The biotracer contained in the bait glows under UV light and so the mice would light up under a UV torch if they had eaten this tasty treat. All of the mice caught bar two juveniles glowed purple on inspection, giving the team great confidence that, with two bait applications, a low sow rate in summer conditions can work for a mouse eradication.

Cats

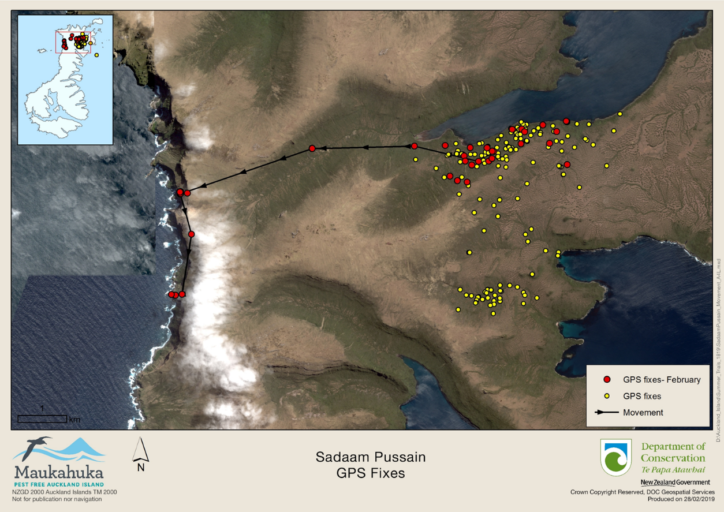

Over the summer leg-hold trapping was carried out at five locations across the island to catch cats and fit them with GPS collars. With no current information on how cats are using the island or the population size, long term location data is key to understanding what the cats are up to and what is needed to carry out a successful eradication.

Image credit: Dept. of Conservation

Seventeen cats were fitted with GPS collars. Larger cats can carry collars with satellite upload capability, allowing the data to be viewed from the office. Smaller cats are wearing collars that can be downloaded via radio telemetry by a team on the ground.

The data from the cat collars show remarkable differences between the cats: some are real homebodies with a tightly defined range and others travel widely. One cat was seen to make a bee-line for the western cliffs after two months on the east coast, possibly driven by the knowledge that the hatching of white-chinned petrels would provide an abundance of food over there.

Another tool investigated was trail cameras. The team wanted to test how well a grid of trail cameras would pick up known cats wearing collars. This would help answer a raft of questions from whether trail cameras would work as a validation method in an eradication to what percentage of cats had been caught by the traps in the area to just how many cats are on Auckland Island.

The trail cameras picked up a range of animals living on the island, and in combination with the satellite collar data, has given us some fascinating insights into the behaviour of the cats. Sixteen cats in total were captured, including all five of the cats wearing collars living in the camera grid.

Cats are using even the evilest patches of scrub but were never detected by a camera in the tussock, although from the collar data, scats and trapping data we know that cats do frequent the tussock tops. They (along with the humans of the island) appear to prefer the coastal rata forest. A few cats were snapped out and about in the daytime, and a few ranged incredibly widely across the study area.

A final piece to the cat puzzle will be given by the collection of cat scats brought back from Auckland Island. DNA analysis of the scats will hopefully tell us how many individual cats there are in the area, allowing us to see if the trail camera network captured all of them. It will also shed light on what, and where, the cats are eating. The collection of scats was greatly helped by the magnificent nose of one of the two cat dogs who spent two weeks on the island.

What next?

So what next for Maukahuka Pest Free Auckland Island? Data analysis, reporting, further trials investigating the use of cat specific toxins on the island, working out how to operate in the Subantarctic environment during the winter and most importantly working with partners and Treasury to source funds and build support for the project to become operational.

This is an enormously ambitious project in a wild and ruggedly beautiful place. There’s a lot of work still to do, but hopefully in ten years’ time we can leave Auckland Island to the seabirds and megaherbs that should be calling it home.