Aotearoa New Zealand has made huge strides towards the Predator Free 2050 (PF2050) goal, but many believe we need new technologies to get to the finish line. It might sound futuristic, but Artificial Intelligence (AI) is already hard at work in the predator free movement, and there are lots of exciting developments on the horizon. We caught up with three kiwi organisations looking to work smarter, not harder.

ZIP puts AI to the test

Phil Bell says his dad (legendary conservationist Brian Bell) “was very good at blurring the work-life balance”. Phil grew up hand-feeding kākāpō and chasing takahē around remote parts of the country, and he simply never stopped. Now he works as Innovation Director at Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP), developing cutting-edge predator detection technologies (amongst other things).

AI is becoming key to the success of the Predator Free South Westland project, with more than 350 thermal imaging cameras installed throughout the Whataroa-Butler Valley and South Ōkārito forest. The cameras are designed to sit in the remote and rugged landscape alongside ZIP’s automatic mayonnaise dispenser (MotoLure) for up to a year before they need servicing.

The cameras wait and watch for predators to come past. When a warm animal comes into the camera’s footprint, it sets off the sensor, waking the camera up to record a 20-second video. Once a day, it runs all the recordings through an on-board algorithm that can identify stoats, rats and possums. It then sends the neatly summarised data through to ZIP so the field team can take action if needed.

It used to take a lot longer to do this mahi. Before AI cameras and MotoLures, someone had to tramp in every month or so, change batteries and SD cards, re-lure the cameras and rebait traps before traipsing back out. They then spent hours going through the images to identify each animal. It was time- and cost-intensive.

“We need to prove that predator elimination is a viable thing, and this technology is the key piece to that puzzle. Pulling off Predator Free South Westland demonstrates to Aotearoa New Zealand what predator free looks like,” Phil says.

Phil understands that replacing people with machines is often thought of as a bad thing, but he believes AI is vital to achieving PF2050. “AI makes it possible for us to do so much more with the people and resources we have – these cameras will watch the site so we can move on to the next one. I must admit, I quite like the idea of putting myself out of a job because then we know we’ve won,” he says.

Making noise with The Cacophony Project

The Cacophony Project is a not-for-profit enterprise dedicated to creating smart tech to bring back the birds. Started by Grant Ryan, the company creates open-source technologies, free for anyone to use and collaborate on. He’s certainly ambitious. Grant believes they can make trapping 80,000 times more effective with AI.

Grant’s brother Shaun Ryan, who has a PhD in AI, runs the sister company, 2040, which manufactures, sells, and supports the Cacophony technology. He’s passionate about machine learning, describing himself as a “relentless inventor”. Shaun and his team are developing a suite of technologies to lure, observe, identify, and eliminate introduced predators.

One of their first projects was an automated Bird Monitor, which records bird calls and uploads them to the cloud. The monitor shows changes in bird populations over time and measures the success of predator control operations.

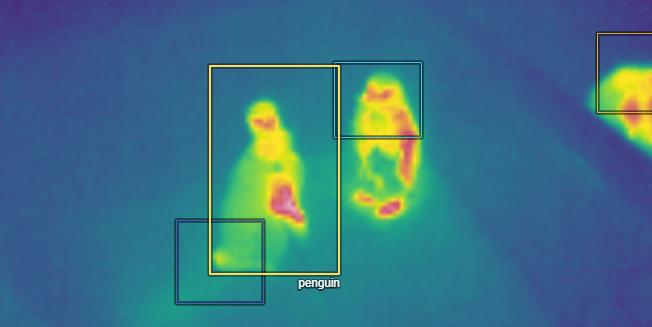

With funding from Predator Free 2050 and others, Cacophony developed a rugged thermal camera that can withstand harsh New Zealand weather. Like a human brain, the camera’s algorithm learns by example – the more possums it sees, the better it gets at identifying them.

An intelligent camera is only the first step.

“For every 100 predators that go past a trap, only one will go into it,” Shaun says. Realising that traditional baits will not get us to eradication, they’re designing speakers and scents to lure introduced predators with sounds and smells.

AI is full of potential. “The technology is really accessible, and there’s a lot of things you can do with it,” Shaun says.

Cacophony is working with the Rakiura Land Trust to develop a smart gate using AI. The gate will recognise penguins and open to let them through for nesting. They’ve also teamed up with regional councils in Otago and Canterbury to tackle the growing wallaby issue. To train their cameras to recognise wallabies, they placed them in the wallaby enclosure at Willowbank Wildlife Reserve.

Shaun acknowledges the next step “is getting the products cheap enough that you can get broad adoptions of them.”

For Cacophony, collaboration is the key to success. The company works with ZIP and Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research, sharing ideas and tech, and there’s no sense of competition.

“Because our mission is to save the birds, if someone came in and used the tech we invent, that’s fantastic,” Shaun says.

Levelling up at Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research

Al Glen is a senior researcher and wildlife ecologist at Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research. He’s always been interested in the impact of introduced predators on Aotearoa New Zealand’s unique wildlife.

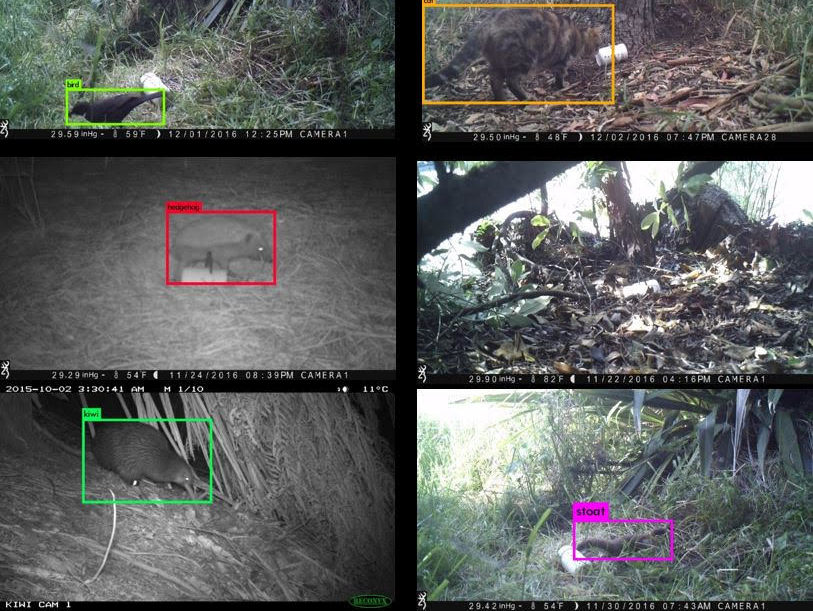

Motion-triggered cameras (known as ‘camera traps’) are great for detecting elusive animals, but processing the thousands of images they produce can be time-consuming and expensive. Al has worked with a range of people to create image recognition software that can process images without the need for human eyeballs. The software is trained to identify stoats, ferrets, weasels, rats, possums, mice, feral pigs, cats, rabbits, and hares, and they’re working on wallabies too.

Al says, “the software will make our monitoring a lot more time and cost-efficient,” and thinks it should be publicly available via the Trap.NZ website in the coming months.

Al acknowledges that thermal cameras can pick up more animals but says the conventional ones are cheaper. “For nationwide eradication, we need technologies we can buy by the thousands,” he says. “They both have their place.”

Traps are the next step. “We’re not going to achieve nationwide eradication until we can roll out more effective traps,” he says.

Al hopes they’ll have a trap that can recognise different predator species and respond accordingly in two or three years. “For example, if it sees a stoat approaching, it might squirt out a spray of a stoat pheromone to lure it in,” he says.

They’re trialling sounds, scents and different visual lures to see what works best for each animal. Like ZIP and Cacophony, they’re big on collaborating – working with conservation groups and regional councils to test and trial the tech.

Al believes PF2050 is possible with advances in AI. “In a couple of years, we’ve got machine learning models that can identify a whole range of species. I’m astounded by how far we’ve come already,” he says.

Is AI the key to Predator Free 2050?

Phil, Shaun and Al all say yes – advances in technology are vital to achieving the predator free vision.

“Predator Free 2050 is achievable – I wouldn’t be doing this work if I didn’t believe that,” says Phil. “But we’ll need new tech to get us there.”

“I think it’s a fantastic aspiration, and the proposed time frame is pretty good. If you look at the tools and knowledge we have now, we won’t get to eradication, but that doesn’t mean that we won’t be able to in 20 years from now,” Al says.

Shaun agrees – “If you think about what the technology was like 20 years ago and how far we’ve come in that time, this kind of technology will be way further along in 20 years.”

Keen to get involved?

There are lots of things you can do to help:

- If you’re a clever engineer or computer specialist, get involved with Cacophony’s open-source projects.

- Use Landcare’s monitoring tech free of charge when it’s available.