ON THIS PAGE

Why should Aotearoa New Zealand be predator free by 2050?

Aotearoa New Zealand is home to many unique and ancient species of birds, frogs, lizards and plants. Our animal and plant life is distinct because we have been geologically isolated for 85 million years since we split from the supercontinent of Gondwana.

Many of our species are found nowhere else on Earth and this isolation makes them vulnerable to introduced predators such as rats, stoats and possums.

Making NZ predator free by 2050 will allow our native wildlife to flourish once more.

The Predator Free 2050 mission is focused on the complete removal of five predators: rats, stoats, ferrets, weasels and possums. Other introduced predators such as hedgehogs and feral cats also have an impact on our native flora and fauna.

Predator Free 2050 has already been a catalyst for action. Individuals, hapū, families and communities have been quick to embrace the goal.

Our national map shows the predator control work being undertaken throughout the country by local community groups, hapū, iwi and private landowners as well as DOC, OSPRI and regional councils.

Why is Predator Free 2050 so important?

Firstly, we’ll protect our precious native species, improve our biodiversity, create greater ecological resilience and restore our unique ecosystems.

We’ll provide a legacy for future generations and our natural spaces provide us with a unique and unrivalled way of life. It’s becoming more difficult to show our children and grandchildren the environment we grew up in and the range of wildlife our ancestors experienced 100 years ago no longer exists.

We’ll attract visitors to New Zealand seeking to experience our unique wildlife and pristine landscapes.

There are immediate benefits too. Being part of community conservation and outside in natural surroundings can improve health and volunteering as part of a group strengthens communities.

Importantly, both rural and urban communities have a vested interest in the goal.

We believe a predator free New Zealand can provide common ground for all New Zealanders.

Who are the key players?

- The Predator Free NZ Trust (that’s us!) — we are an independent charitable organisation established to encourage, support and connect New Zealanders in getting involved in the predator free movement.

- The Department of Conservation — DOC provides leadership to the Predator Free 2050 programme. Their Predator Free Rangers provide regional support to predator free projects and their Tiakina Ngā Manu programme is aimed at protecting our most at-risk native animals on public land.

- Predator Free 2050 Ltd is a company set up by the government to invest in large landscape scale projects and breakthrough research.

- There is strong support from farmers and primary industries. Amongst others, OSPRI, Federated Farmers, and the Ministry for Primary Industries are all involved in predator free work.

- ‘Breakthrough research’ is being undertaken through multiple agencies, including New Zealand’s Biological Heritage National Science Challenge, Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research, The Cacophony Project, Zero Invasive Predators and many universities.

- Iwi and hapu are involved at every level of the Predator Free movement, from advising on strategic direction to implementing their own projects. Poutiri Ao ō Tāne and Taranaki Mounga are examples of two landscape scale projects that iwi are heavily involved in.

- Local and regional councils are increasingly taking on the predator free goal, e.g. Auckland Council as part of the Pest Free Hauraki Gulf.

- NGOs like Forest & Bird and WWF, charities like Save the Kiwi and the Sanctuaries of New Zealand are focusing effort and resources on a predator free future. The Next Foundation is a leading investor in predator free initiatives, including Project Janzoon in Abel Tasman National Park, and the Taranaki Mounga Project.

Why are New Zealand’s native species so precious?

New Zealand is an internationally recognised ‘hotspot’ for biodiversity. Our long isolation from other land masses, as well as our diverse ecosystems, have allowed very special flora and fauna to develop. Today, a large number of New Zealand’s native species are classified as threatened, meaning they’re at risk of becoming extinct in the near future. For millions of years, species like kiwi and kākāpo evolved with no threat from mammalian predators such as rats, mustelids (stoats, ferrets and weasels) and possums. When these predators were introduced, our native species were particularly vulnerable to them.

For 85 million years, New Zealand was isolated from the rest of the world. This separation allowed our flora and fauna to take a unique evolutionary path. The result was 80,000 endemic plants, animals and fungi including incredible species like carnivorous snails, giant flightless birds, and lizards (skinks and geckos) that – most unusually – give birth to live young rather than producing eggs.

Before humans arrived, New Zealand was almost entirely covered in forests teeming with species that were found nowhere else in the world. But, as people cut down forests and introduced predators from overseas, New Zealand experienced a huge biodiversity loss.

Today, New Zealand has one of the worst extinction records of any country. To combat this, in 2015 the Government announced the Predator Free 2050 goal – to rid all of New Zealand of mustelids, rats and possums by 2050.

Why do some species become extinct?

Species have been going extinct since the world began, either because of naturally-occurring environmental conditions or as a result of human actions.

Extinction can happen very suddenly or occur gradually over thousands of years.

The main human actions that cause extinction are over-harvesting, pollution, habitat destruction, and introducing pests and weeds.

Which species are endangered?

Compared to other countries, New Zealand has a high number of native flora and fauna that are classified as endangered or threatened. This means they’re at risk of becoming extinct in the near future.

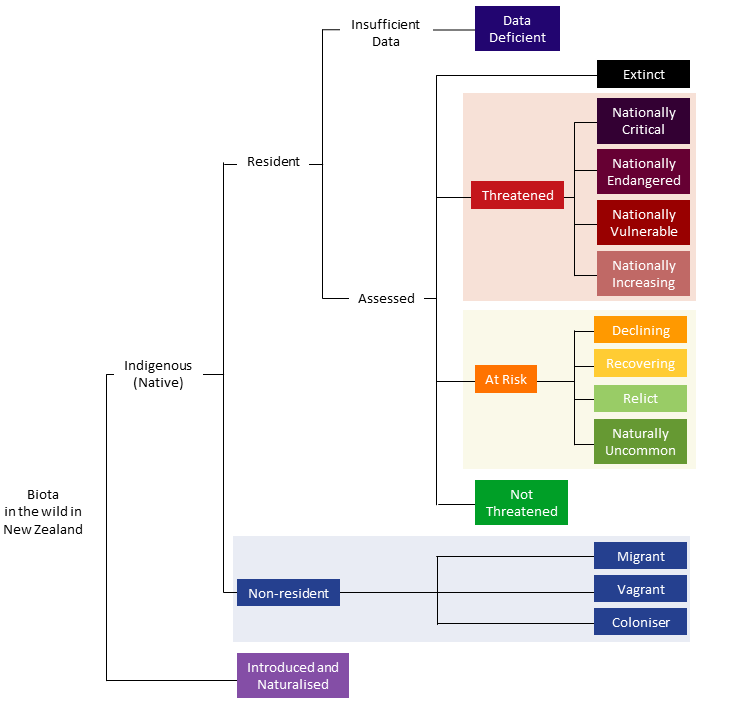

The risk of extinction is confirmed based on several benchmarks, including population size, the rate of growth or decline, and how long the species has been in New Zealand. Over a period of time the numbers are reviewed to see whether anything has changed.

Despite the efforts of conservationists, 4,000 of our native species remain under threat of extinction. Among our plants, 289 species are threatened and 749 are at risk, meaning that without intervention they will be extinct within the next century. This is nearly 40 percent of the total number of New Zealand’s indigenous plant species. Of the 417 bird species still present in New Zealand (56 are already extinct), over 40 percent are now threatened or at risk. Our indigenous lizards are also extremely vulnerable, with approximately 85 percent threatened or at risk.

Our frogs/pepeketu

Originally, New Zealand had seven species of native frog.

Sadly, since the arrival of humans and introduced predators, three species have gone extinct.

The four remaining species are:

- Archey’s frog (critically endangered)

- Hamilton’s frog (endangered)

- Hochstetter’s frog (vulnerable)

- Maud Island frog (vulnerable)

New Zealand’s native frogs belong to the ancient genus Leiopelma, a group of frogs that have changed very little in the last 70 million years. Our native frogs exhibit a number of primitive traits that separate them from most other frogs.

- They don’t flick their tongues to catch prey

- They don’t croak loudly at night

- They have round eyes (not slit)

- They don’t lay eggs that hatch tadpoles

- They don’t have webbed feet

All four of New Zealand’s frog species have severely reduced distribution and population sizes. Hamilton’s frog is one of the rarest frogs in the world, with only about 300 frogs contained in one rocky area of predator-free Stephen’s Island in Marlborough. Our native frogs are particularly vulnerable to predation from ship rats, and pests such as pigs and goats disturb their habitats as well.

Our bats/pekapeka

Due to New Zealand’s unique evolutionary path, our only native land mammals are thumb-sized bats. Once found all around New Zealand, they are now a very rare sight and restricted to small patches of forest.

The short-tailed bat (nationally vulnerable, declining) and the long-tailed bat (nationally critical) are the only two species of native bat left. New Zealand’s largest bat species, the now extinct greater short-tailed bat, died out soon after Pacific rats arrived with Māori settlers.

Without further intervention, our two remaining native bat species will most likely be extinct on the mainland within 50 years.

Our birds/manu

New Zealand is known as the ‘land of birds’ for a reason.

In the absence of mammalian predators, New Zealand’s unique natural environment meant our native birds could evolve in ways not seen anywhere else in the world.

Some of them became flightless, while some developed increased life spans but slow breeding rates, as well as producing small clutch sizes and large eggs.

Several native species are nocturnal, and others have a large body size.

Our most severely threatened birds are ‘nationally critical’ and this means they are facing an immediate high risk of extinction. Here are a few of our rarest, nationally critical birds:

- Kākāpō (nationally critical). The kākāpō is one of New Zealand’s most well-known threatened birds, with a current population of just over 200. They are big, flightless birds that create their nests on the ground, making them extremely susceptible to predators such as cats, rats and stoats.

- Kākāriki karaka (nationally critical). Kākāriki karaka (orange-fronted parakeets) have been declared extinct twice, once in 1919 and again in 1965. Each time, the birds were concealed deep in the beech-forested valleys of Nelson and Canterbury. Kākāriki karaka are the rarest parakeet and forest bird in New Zealand.

- Tara iti (nationally critical). The tara it (New Zealand fairy tern) is probably our most endangered indigenous breeding bird with a population of around 45 individuals that includes approximately 12 breeding pairs. They are highly susceptible to predation, human activities and environmental events.

Our flora and insects

New Zealand has 2,363 species of indigenous plants and 80% of them are not found naturally anywhere else in the world. Of these, over 30% are threatened or uncommon. Our endangered plants are often impacted by:

- Habitat loss due to destruction and/or degradation.

- Grazing by introduced predators.

- Encroachment of invasive weeds.

Kākābeak (nationally critical) are known for their brightly-coloured flowers resembling a parrot’s beak. Wild populations of kākābeak are disappearing extremely rapidly with the Northern kākābeak now only surviving in cultivation.

Deer, goats, rabbits, possums, hares, cattle, sheep, snails, slugs, caterpillars, bugs and aphids all love to eat kākābeak, some travelling long distances to get a mouthful. Conservationists are working hard to protect wild kākābeak populations by controlling predator populations.

The situation with endangered plants becomes more complex because there is a high degree of specificity between plants and their insect fauna.

Endangered plant species are very likely to have one or more rare and endangered insects associated with it.

Why undertake predator control?

New Zealand’s native flora and fauna are particularly vulnerable to introduced predators. The threat of introduced predators was first identified at the beginning of the 20th century and through the efforts of scientists and experts from Wildlife Service, the Department of Conservation (DOC), TBFree (OSPRI), regional councils and others, it has become increasingly better understood.

Throughout the 20th century, government agencies invested many hundreds of millions of dollars in controlling mammalian predator populations. Their expertise is now internationally recognised.

In 2016, the New Zealand government announced an ambitious vision – Predator Free 2050. The goal is the complete removal of rats, stoats, and possums – the three most damaging introduced mammalian predators to our natural taonga. Reaching this goal will allow our native species to thrive again as they once did.

Many thousands of New Zealanders, generally as volunteers, individually or in groups, have dedicated millions of hours to controlling rats, stoats and possum populations all over the country.

You can get involved by learning more about introduced predators, trapping in your backyard and joining a local community group.