It hasn’t got the huge international fanbase of the kākāpō, the show-stopper song of a tūī, bellbird or kōkako or the national icon status of kiwi. Ngutuparore – the wrybill – is a modest little river plover that no-one takes much notice of. But the wrybill’s got something that’s not found in any other bird in the world.

All wrybills have a lateral bend in their beak. Their beaks bend sideways to the right, probably allowing them to look for insect larvae, water invertebrates and sometimes small fish, under the riverbed stones. The purpose of the bend in their beak has never been proven however.

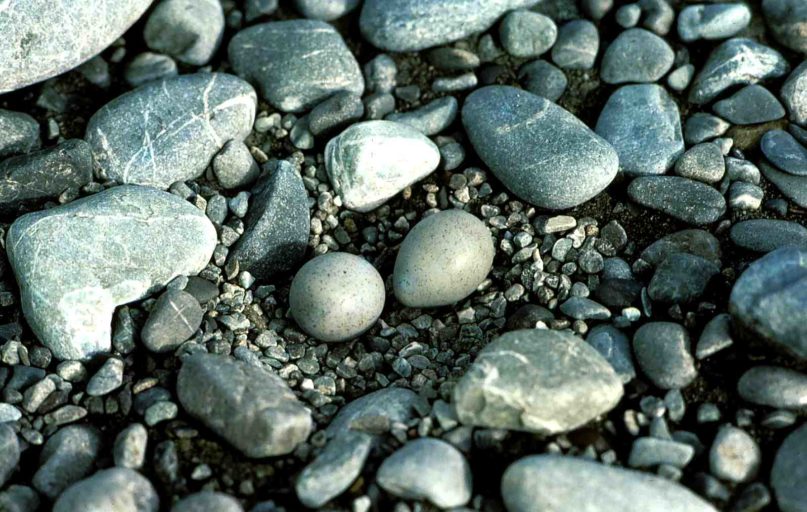

Spotting the bird with a kinky beak can be a bit of a challenge. Their colouring is adapted for camouflage from aerial predators like hawks, gulls and owls and they blend in well with the riverbed stones. There chicks and eggs blend brilliantly too. Chicks freeze to escape detection (especially when small), and swim well from a few days old.

Camouflage isn’t so successful with mammalian predators armed with a super sense of smell, but wrybills do have other survival techniques. Get too close to a wrybill nest and you’re likely to spot an ‘injured’ adult bird, luring you away with a talented theatrical performance of wounded vulnerability.

The adult bird will run around with the wing near the intruder trailing on the ground, the other lifted in the air; the feathers of the rump are raised; the tail spread fanwise, and depressed so that the tip is almost on the ground; and the bird all the time makes a continuous purring noise.

Wrybills are also surprisingly staunch.

They form a monogamous bond with their mate and will return to the same territory each year to breed again. If their mate does not return, the bird will move territories. Nesting territories are between 1 and 11 hectares in size (average 5 hectares) and fiercely defended. Territories may overlap with those of other species (e.g. banded dotterel, black-fronted tern, pied stilt), but are vigorously defended against other wrybills.

Wrybills show a strong tendency to return to the same nesting territory each breeding season and young birds also show a strong tendency to breed close to where they were hatched. Each summer on the braided rivers of Otago and Canterbury, favouring open shingle areas without weeds. The main breeding rivers include the Waimakariri, Rakaia, Rangitata, Waitaki and Ashley.

Nesting sites are pretty basic, however – just a shallow scrape, lined with many small stones, in an area of large stones or sand. The eggs look a lot like stones themselves. Two eggs are laid and are incubated by both parents (but more so by the female) for 30 to 36 days. The chicks have downy feathers on hatching, grey-to off white above and white underneath. Both parents care for the chicks, which fledge after around 35 days and are independent from then on. Young birds start breeding when they are two years old.

In contrast to their stroppy territorial behaviour during the breeding season, wrybills like to roost in large flocks during winter. After breeding, around late December till early February, they leave their breeding sites and migrate to shallow estuaries and sheltered coastal areas in the North Island. These areas include Firth of Thames, Manukau Harbour, Kaipara Harbour and Tauranga Harbour.

On their wintering grounds, they feed on inter-tidal mudflats in harbours and estuaries. High-water roosts are usually near foraging areas, usually on shellbanks and beaches and occasionally on paddocks. In the upper Manukau Harbour, birds regularly roost on roofs of large buildings – sometimes even on the tarmac at Auckland Airport.

Sometimes these flocks will perform large aerial displays, usually shortly before the spring/summer migration south again. The highly-coordinated aerial manoeuvres of these flocks have been described as resembling a flung scarf. On migration, flocks generally follow coastlines. A high proportion of the population passes through Lake Ellesmere on both migrations.

Wrybills are at their most vulnerable during the breeding season. Threats include predation, flooding during nesting time, habitat degradation and disturbance from vehicles along the riverbeds. Introduced mammalian predators such as ferrets, stoats, weasels and hedgehogs pose a significant threat. As wrybills prefer an open clear area of shingle on the river bed to nest, introduced plant species such as gorse, willow, broom and lupin, all threaten the wrybills habitat as they spread over the landscape easily and quickly.

Being a bit different can make you more vulnerable too. Like the huia which was also famed for its unusual beak, wrybills were once sought after by collectors. The population declined during the 1800s as they were collected as museum specimens. In 1940 they were protected and the population has increased from around 2000 birds to 5000 birds today.

If they can avoid predators and other hazards both natural and unnatural, wrybills can live for 22 years or more – and each year they will migrate between the North and South Islands, travelling 700-1000 km each way – that’s about 44,000 km of long-distance flying during their lifetime.