Come behind the scenes with predator free apprentices Aidan and Jamie at Mammalian Corrections Unit (MCU) as they help establish an intensive trap network in an old-growth forest.

Hikaroroa (Mt Watkin) looks down across one of the last large patches of old-growth broadleaf-podocarp forests north of Dunedin. Monitoring showed mustelids as one of the major ecological threats to native fauna in the forest reserve. MCU started work in the reserve in 2021, but a new, more intensive mustelid trap network would be needed to suppress numbers and guard against reinvasion.

But first, building and scouting

The project needed a lot of traps, so it was time to get building! The workshop days were repetitive but rewarding. The process: unload the planks off the flatbed onto the rollers, saw them all to size, cut grooves for the baffles, nail it together in the jig, screw in the DOC200s and chuck on our stylish logo. Bam! Now repeat!

For the 160 traps we’d prepared, we scouted ridges, gullies and old tracks in the reserve for the best places to run the line. The traps were spaced 100m apart on lines 800m apart – distances that should put a trap in every stoat home range.

The terrain was rough and access limited, so using a helicopter was the most efficient way to scout. While scouting our trap lines, we sought out any clearings or canopy holes where a helicopter could drop bundles of traps.

From here, we switched gears from stomping around the bush to sitting in front of screens. We loaded the GPS points from our scouting missions and scoured satellite images for clearings for the remaining drop sites. We GIS mapped the network and worked on the logistics of the installations.

Get ready for the drop

The morning of the drop, we loaded a flatbed truck with all the traps and departed Dunedin accompanied by a fleet of smaller 4WDs. The convoy reached the maunga by mid-morning and 4WD’ed around the perimeter of the reserve, dropping and installing boxes on the easier-to-access fencelines. We then unloaded the helicopter bundles and spent the night in a kind neighbour’s luxury shearer’s shed.

It was claggy the next morning as sea fog rolled in and covered the valleys. By 10 o’clock, the fog had lifted, and the helicopter was en route. The quiet forest sounds of Hikaroroa were replaced by the whirring as it landed near our staging area. We hooked the bundles beneath the helicopter one by one and took turns hopping in and directing the pilot to the drop locations. The whole team was tense, watching our hard work fly off in the sky, but in the end, all the aerial deliveries went smoothly despite some tricky drops on long lines through the canopy.

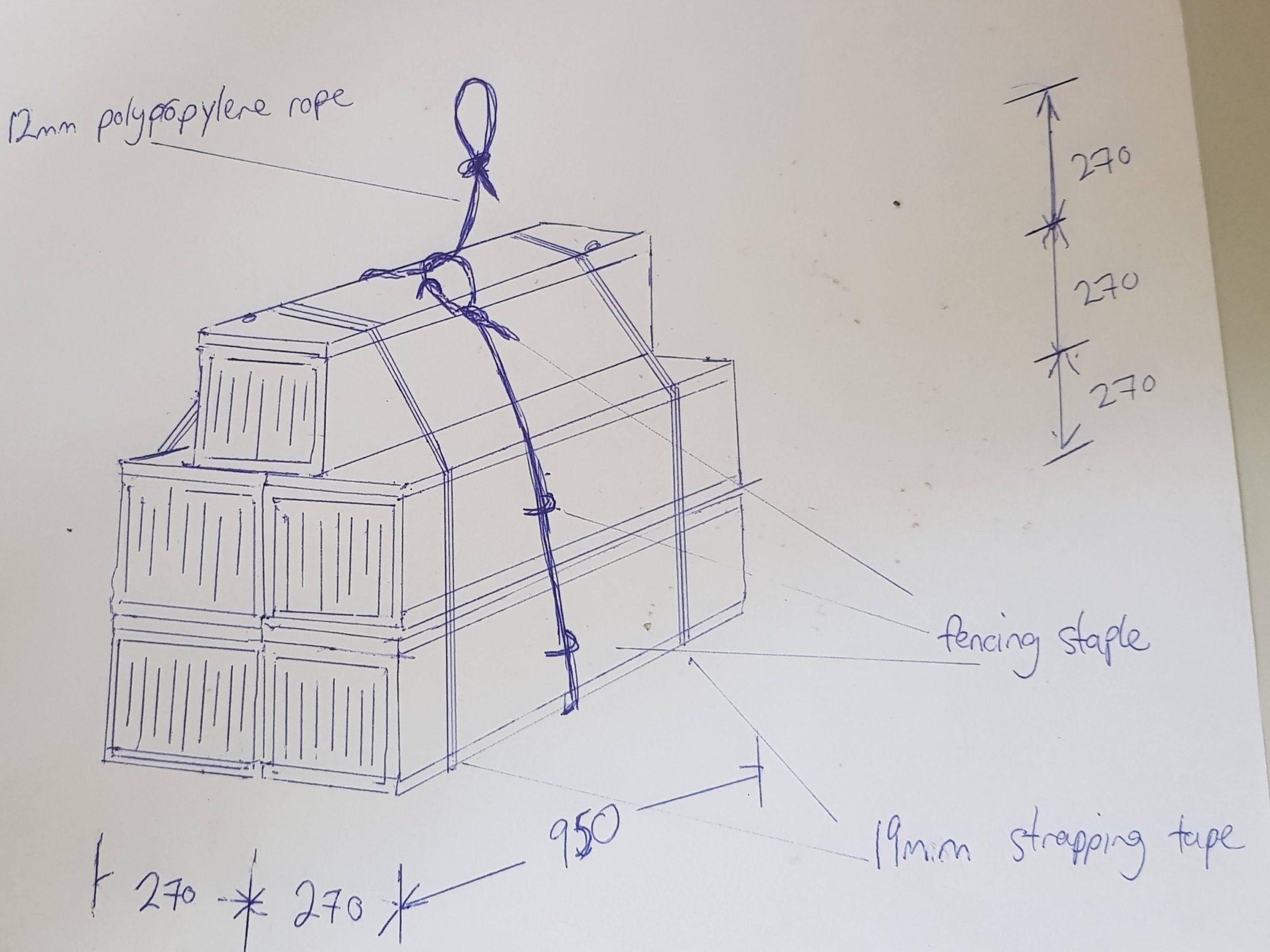

The following days were less exciting than the helicopter deliveries. It was time to just put on some music and lean into the heavy packs. We set off up the Waikouaiti river to open up the drop bundles and spread the traps out along the trap line to their new homes. Then rinse and repeat. The process: find the bundle, strap a trap to the pack frame, walk downstream in 100m intervals, find or make a flat spot, clear the vegetation, hammer rebar, staple traps, record GPS point. Repeat until the bundle is empty. Walk to the next bundle.

Our reward was some good kai back at camp and a heavy sound sleep in our tents at the end of the day.

The aftermath

The mustelid network is now serviced monthly over two days. The network has been upgraded with cat and possum traps, and monitoring data has continued to be collected to show how effective our suppression efforts have been. The next steps for our work in the reserve will be establishing biodiversity monitoring networks to better quantify and understand the recovery process of our native species.

The Predator Free Apprentice Programme aims to grow the number of experienced animal pest control specialists to support the predator free vision. The two year programme, funded by Jobs For Nature, provides a career path for people wanting to work in predator control.