In the struggle to achieve its predator free status, Kaipupu Sanctuary faced unexpected challenges, including inadvertently training a population of rats to avoid traps.

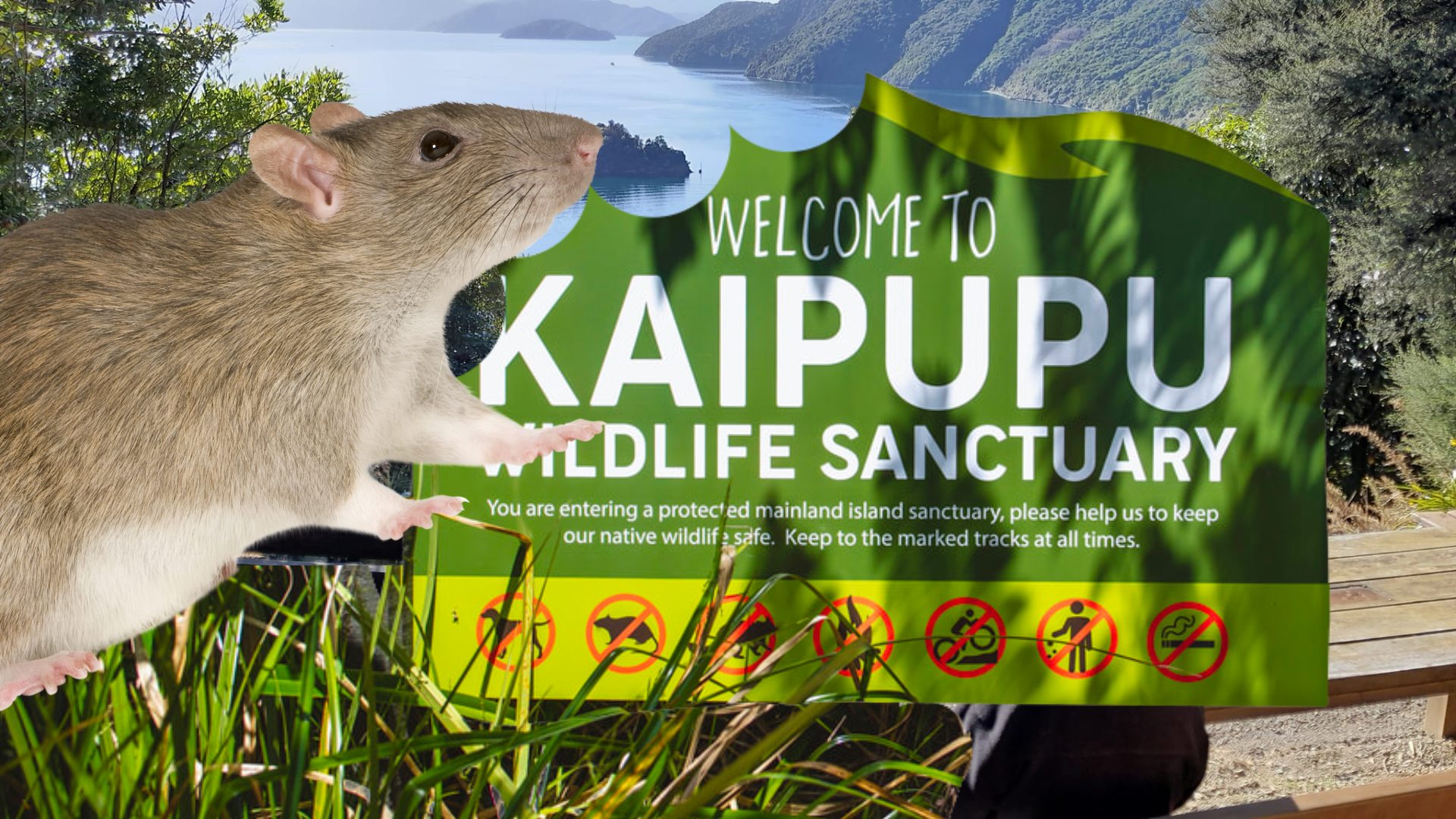

Stepping onto the floating jetty at Kaipupu Sanctuary in Waitohi (Picton), you’re greeted by a wall of native bush and a chorus of birdsong.

The peninsula, a short jaunt from the town centre, is surrounded by the waters of Picton Harbour and Shakespeare Bay and protected by a 600-metre predator-proof fence at its southern end.

Unlike the calm waters which surround it, achieving its recent predator free status wasn’t all smooth sailing.

“It’s almost like they had been to rat school”

Over the first decade of its existence, the sanctuary faced several setbacks, including inadvertently training a population of rats to be wary of traps.

In the early years, the sanctuary tried putting mouse traps inside donated bait stations to bolster its trapping efforts.

“In our naivety, we said, ‘oh, bait stations will be good to house mouse traps’,” long-time volunteer and founder of local conservation group Picton Dawn Chorus, James Wilson recalls.

After a while, the team was perplexed about why they weren’t catching as many rats as before.

Then came the epiphany.

“[It was] these damned mouse traps in the bait stations, which rats could easily get to. They were going in there, getting their nose smacked, but not being killed. They got away and became trap shy.

“[It turns out it] was the craziest thing we could’ve done. But no one told us we were doing it wrong.”

The mouse traps were all baited with peanut butter. Instead of being alluring to the rats, it had become “a danger sign”.

Rats that survived their warning snap went on to breed and appeared to pass on that knowledge to subsequent generations.

“It’s almost like they’d been to rat school,” James says. “They learned from their parents that they don’t touch peanut butter or traps.”

An independent review in 2019 recommended a toxin operation to target the population of trap-shy rats. The exercise was completed the following year with great effect. Since then, Kaipupu Sanctuary’s monitoring tunnels have been rat-free.

James suggests that because rats seem to pass information about their close encounters between generations, using various trapping methods and techniques is most effective to keep the population low.

No rats and abundant bird life

The 40-hectare mainland island is jointly owned by the Ports of Marlborough and the Department of Conservation. The relatively small piece of peace, nestled between two busy shipping lanes, was loaned to the community in 2005 to create a haven for native species.

A pest-proof fence was installed in 2008, and just under 15 years later, that vision has been realised.

Late last year, the sanctuary declared itself predator free after making it two years with no rats detected in their monitoring tunnels.

“It was a stunned silence, really,” James recalls the milestone.

“In 2012, there wasn’t a lot of bird life. There were a lot of weeds and a lot of open space. There was a block of original forest, another in reasonable replenishment, and another that was the holding paddock for the former freezing works there.”

It was also home to an abundance of ship rats and some possums.

“If you go there now, there are no rats, there’s abundant bird life, and the bush is just thriving. It’s a fabulous place to go,” James says.

The intensive trapping operation and dedication of its volunteers have already paid dividends with a recent sighting of a ngirungiru (South Island tomtit) for the first time since at least 2005.

A population bottleneck

New research confirms the sanctuary’s intensive trapping operation brought rat numbers down so much it created a population bottleneck.

Published in the peer-reviewed journal Biological Invasions, the paper suggests rats at Kaipupu Sanctuary became genetically distinct from neighbouring populations outside the fence.

The authors say the results from DNA taken from rat tails show natural and man-made barriers effectively limit outside rats from introducing new genes into the Kaipupu population.

Despite being able to swim 500 metres to the sanctuary, rats are more likely to move between connected forest patches around Picton.

In the cases where rats do make it to shore, Kaipupu has been able to catch them before they have a chance to establish a population.

James says the experience of Kaipupu Sanctuary provides “excellent lessons” for other trapping groups and is being applied to the neighbouring forest in Picton.

“It’s almost inevitable the birds fly out of the sanctuary and are subject to the same risks they would’ve been in the sanctuary before the trapping started,” he admits.

That’s why Picton Dawn Chorus focuses on creating a halo of bird protection by trapping on the mainland outside the sanctuary. It appears to be working.

“I do think Picton Dawn Chorus is playing its role because now we’re bringing down the rat numbers to more acceptable levels,” James says.