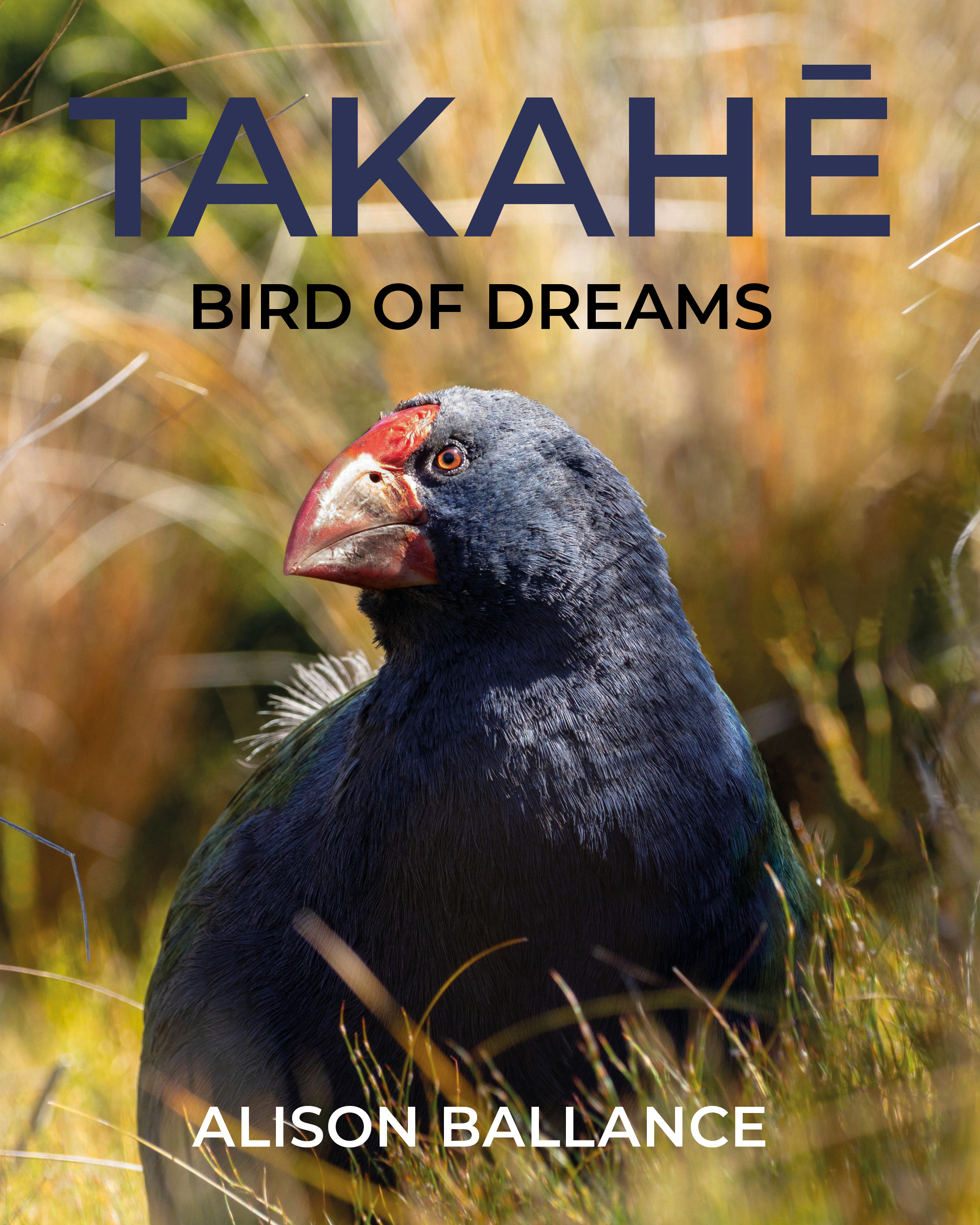

Conservation success stories don’t get much more dramatic than the tale of the takahē. Takahē: Bird of Dreams takes readers on the rollercoaster of takahē conservation over the last 75 years.

Written by award-winning broadcaster, writer and zoologist Alison Ballance, this beautiful book is filled with photographs of the birds and the people who’ve cared for them. Alison is no stranger to takahē, and the book includes diary entries from her own trips into Fiordland in search of the birds. Takahē: Bird of Dreams is a must-have for any conservation or nature nerd.

Alison is a master storyteller, and the book starts with a chapter written from the point of view of Hāpara – a wild female takahē born and raised in the Murchison Mountains in Fiordland. Readers follow Hāpara (Māori for ‘dawn’) from her conception, incubation and hatching through teenagerhood, courtship and motherhood. Through Hāpara, we learn that takahē are stoic and steady; they’re loyal(ish) partners and loving parents.

We also learn that, despite their considerable bulk, takahē are vulnerable to one of our most rapacious and deadly introduced predators – stoats. Hāpara’s life is marred by tragedy – many of her chicks are lost to the voracious mustelids, and, eventually, Hāpara herself is attacked. It’s an effective opening for the book – and it sets the scene for one of the biggest challenges the Takahē Recovery Programme faces – what to do about the ongoing threats to the birds.

There’s no such thing as too many takahē

The last few chapters of the book leave readers with a strong sense of just how important Predator Free 2050 is to the future of this taonga species.

Takahē now face a wonderful problem – there are more birds than places to put them. Island sanctuaries are not always suitable for the birds, and most are already fully stocked. The team are reluctant to release birds into areas where stoats are still present, and so they need more land on the mainland to push towards predator free.

It’s a great problem to have – there’s no such thing as too many takahē!

Bird’s eye view

It’s hard not to fall in love with these “big, blue chickens.” Takahē are a little bit dinosaur – they seem to offer a window into an older Aotearoa when giant eagles and huge flightless birds roamed the lowlands, forests and mountains.

They are a quintessentially New Zealand sort of bird – flightless, food-obsessed and quirky. They have gorgeous blue and green feathers, chonky red beaks and sturdy legs. Although they share a common ancestor with pūkeko, they’re much larger – takahē are about the size of a turkey.

For the first half of the twentieth century, the charismatic birds were considered extinct. So when doctor and keen bushman Geoffrey Orbell and his three companions discovered takahē toughing it out in a remote Fiordland valley in 1948, the bird became an overnight sensation. Soon everyone wanted to glimpse these enigmatic blue birds that were back from the dead.

Almost as soon as they were rediscovered, scientists and conservationists turned their attention to trying to help the birds recover. Takahē conservation is Aotearoa New Zealand’s longest-running endangered species programme. Thanks to years of hard graft and the dedication of countless staff and volunteers, the birds are now tracking well. At the lowest point, there were just over 100 takahē left – now, there are almost 500 birds. But getting to this point hasn’t been easy.

Dancing on the brink

The book charts the peaks and troughs of takahē conservation since their rediscovery. While the Takahē Recovery Programme is one of the earliest species management programmes in the world, the early decades were tough. Bird numbers remained stubbornly low despite the best efforts of scientists and conservationists.

It took decades to figure out how to get takahē to breed in captivity, and efforts to help them in the wild were hampered by misunderstandings of the threats wild birds were facing.

Despite all the setbacks, the Takahē Recovery Programme ploughed on. Eventually, researchers connected the dots between the dropping numbers of takahē and mast years. The year after a mast is a dangerous time to be a big ground-nesting bird like a takahē or a kea, as hungry stoats have lost their ready supply of rodents and are looking elsewhere for a meal.

As well as breakthroughs in understanding takahē threats, Alison follows the maturing of captive breeding and island management. There are puppets, poo studies and a delightful series of text boxes covering everything from dubious genetic bottlenecks to profiles of individual birds.

It’s a wild ride.

Takahē: Bird of Dreams is published by Potton & Burton with the support of the Department of Conservation’s Takahē Recovery Programme.