With their black eye mask, ferrets might remind you of the Hamburglar. But instead of targeting hamburgers, they are adept hunters with a wide range of native birds and lizards on their menu. They are the least researched introduced predator, so what do we actually know about them?

1. Pets gone rogue

Ferrets are not wild animals by nature — they are a domesticated species descended from wild European polecats and have been kept as pets for over 2,500 years.

In the 1880s, New Zealand farmers unleashed ferrets (crossbred with European polecats to better survive in the wild) to curb the rising rabbit problem. That plan backfired. The ferrets didn’t have much of an impact on rabbit numbers, and instead, New Zealand now has what’s considered the largest feral ferret population on the planet.

Ferrets used to be kept as pets in New Zealand, but a 2002 law banned their sale, distribution, and breeding.

2. Short-sighted but deadly

Ferrets can only see a few feet ahead. But what they lack in vision, they make up for in smell and hearing.

This is bad news for native New Zealand animals, many relying on camouflage or freezing in place to escape danger. These tactics work against visual hunters but are useless against a ferret’s fine-tuned nose.

Take the kiwi, a nocturnal bird with shaggy plumage that blends in with the forest undergrowth. Ferrets are one of the few introduced predators that can and will kill an adult kiwi. Losing an adult kiwi is a heavy blow, as fewer than 5% of kiwi chicks survive to adulthood. Since a kiwi can live up to 50 years and lay around 100 eggs in their lifetime, every adult loss is a significant dent in their population’s future.

3. They have insatiable appetites

Given the chance, ferrets will ‘surplus kill’, meaning they will take down more prey than they can consume at once.

Three ferrets slipped through an extensive trap network and killed at least 21 tītī chicks and two adults on the Otago Peninsula in 2024.

Chicks were found uneaten with telltale wounds to their heads.

All three ferrets were eventually trapped, leaving 17 tītī chicks to survive. In 2019, a ferret killed all the monitored chicks, leaving no survivors.

4. Ferrets don’t control rabbits – it’s the other way around.

Wouldn’t that just get the goat of all those farmers who wanted ferrets released into New Zealand to deal with the rampant rabbit population?

Rabbits are ferret’s main prey, so it seems logical that rabbit numbers would increase without those predators. However, research shows that weather, disease and food abundance are the main factors influencing rabbit populations — not predators.

This “bottom-up” system means the number of rabbits decides how many ferrets survive. So, getting rid of ferrets won’t necessarily make your rabbit problem worse. But if you reduce the number of rabbits, you might see fewer ferrets. Just be aware that if the rabbits disappear, ferrets could start targeting more native animals instead.

5. Reluctant swimmers

Feral ferrets can swim but have never established populations on our offshore islands.

They swim using alternate strokes of the forelimbs (rare among semi-aquatic mammals), an energy-efficient technique that allows them to swim for a considerable length of time.

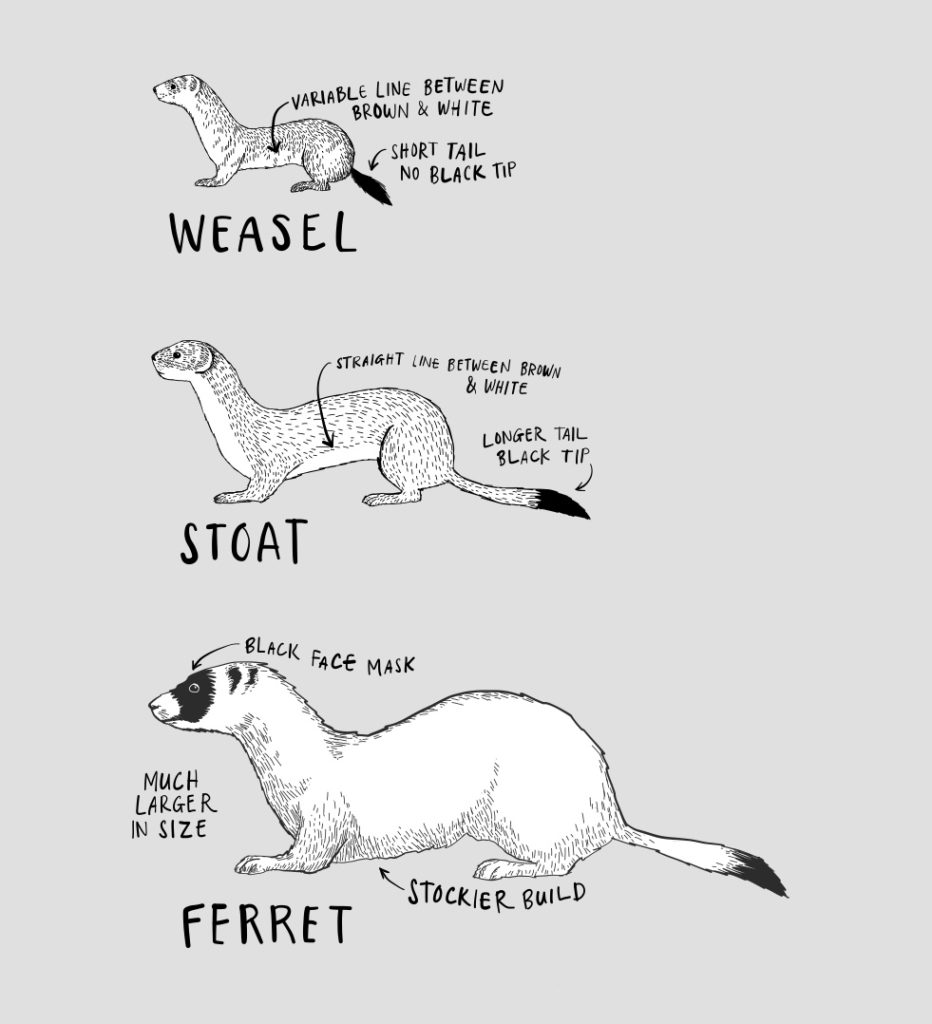

Yet, unlike stoats — known to swim up to 3km to offshore islands — researchers found (PDF, 317 KB) ferrets seem to have a behavioural aversion to swimming, which has kept them mainland-bound

If you’re targeting ferrets, check out our toolkit for advice on trapping and baiting.