Traditional pest-trapping methods weren’t working. Predator Free Franklin spearheaded the creation of Tāwhiti Smart Cage – a cutting-edge solution to the district’s challenging environment.

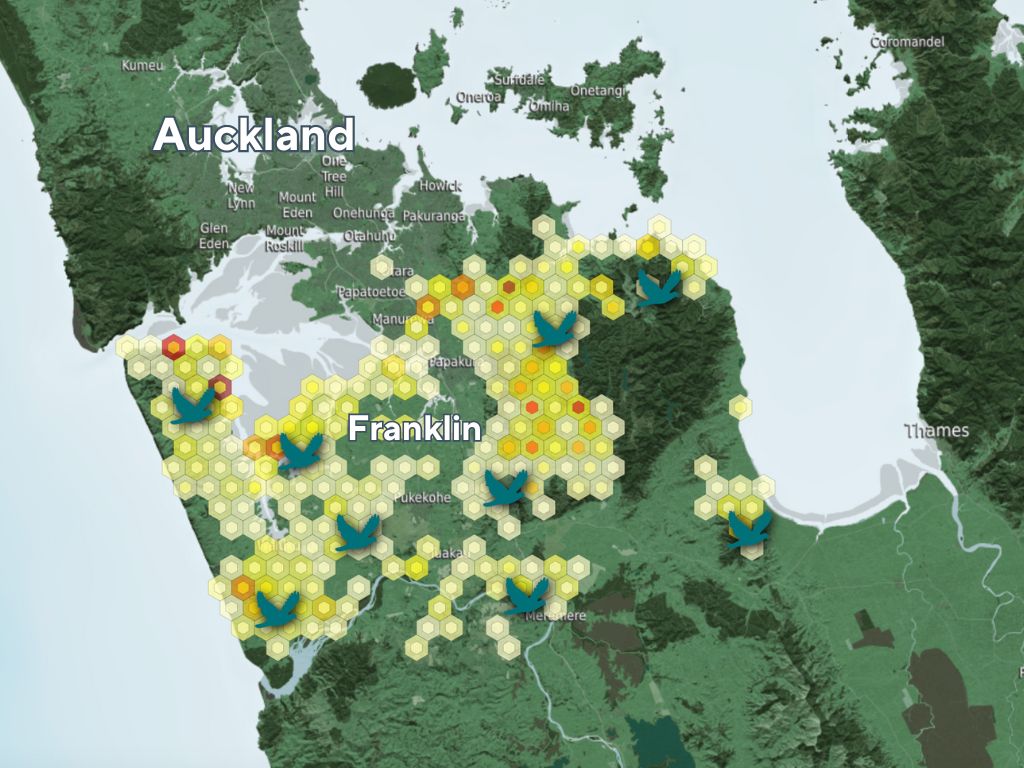

Wild yet beautiful, the sea, rivers, tidal flats, beaches, forests and rural farmland that make up Franklin, near the Auckland Waikato border, also pose a challenge for traditional pest-trapping methods. It’s a lesson Predator Free Franklin learned the hard way.

“When we first started trapping at scale in northwest Waikato, we dabbled with the conventional species-specific methods,” Andy, a keen local trapper, recalls.

“We quickly found our rat traps were being set off by possums, our possum traps were being set off by rats, and locals were spending hours trying to service a tiny area.

“Everyone else thought we were bonkers, yet we were supposedly following best practice.”

Andy says in hindsight, these time-tested methods, which had been effective in other environments, simply weren’t designed for the unique challenges of the Franklin district’s rural landscape. They also required significant people power and effort to maintain and service.

A need for something different

The experience sparked a desire for something more fit-for-purpose. The mission was to develop a trap that could address the specific environmental challenges and streamline the pest control process.

The Tāwhiti Smart Cage was born. It’s a departure from traditional trapping methods, using remote monitoring technology to save time and effort while significantly improving catch rates. Tāwhiti live-captures all types of pest species humanely while reducing the burden on local communities.

The double-ended trap has a sensor that sends a notification via the Trap.NZ app when something has been caught. Rather than relying on toxins, it uses an automatic lure dispenser that tempts predators with an enticing bait – mayonnaise. And it’s cheap too. Over a year, the cost of mayonnaise for baiting the traps is around $2.

Andy says the trap was developed with the time-poor rural community in mind and can help keep them engaged in what has typically been a labour-intensive process.

“Pest control is fairly low on the priority list, but ask this community what pests they would like to be rid of, and most will say ‘the whole lot, as long as it doesn’t hurt the business’.”

Dispatched to dispatch

Of course, capturing a pest species alive is only part of the job. What happens once the trap is triggered?

There are clear obligations in legislation and guidelines, including from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research about dispatching an animal humanely.

The trap owner is ultimately responsible for what’s caught, and notifications help ensure the trap is checked within 24 hours. Catch data from the Tāwhiti shows most are cleared by 1 pm the following day.

Andy says setting traps in places like farms, lifestyle blocks, and even some urban areas is also in the interest of the animal’s welfare because they can be cleared quicker.

Bringing the community together

And while some may be put off by the idea of having to dispatch an animal themselves, Andy says that’s where the benefit of community comes into its own.

“We have a number of trappers who’ve purchased Tāwhiti with the intention of the neighbour doing the servicing – that’s a great collaborative model,” he says.

He believes it is helping create a strong community in Franklin, which is invested in a common cause.

“It’s not unusual to hear discussions in the supermarket aisles starting with ‘I see that trap went off, what was it?’ This is the awareness desperately needed for communities to own and share the problem.”

While it quickly gained favour with the locals, it’s also been officially recognised as an award winner, scooping the top prize in the Innovation category in the 2022 Auckland Mayoral Conservation Awards.

The future of Tāwhiti

Trap.nz data shows the Tāwhiti has been more successful at trapping ferrets, hedgehogs, and feral cats than the current conventional best practice methods, and around the same for other pest species.

Anecdotal feedback from users also suggests the same thing.

“Eighteen predators taken out with the two cages since installing six weeks ago. One ferret in the DOC200,” one says.

“I’m stoked with the one I have at home. Seven ferrets in 14 days, and two about a month later, plus numerous hedgehogs, rats and possums”, reports another.

While it was made initially as a community tool for Franklin, it’s now in use across the country, though not without some initial reservations.

“There was some nervousness around sending traps to the West Coast due to weka,” Andy recalls.

But early reports are of weka being happily released and feral cats dispatched.

A third generation of the trap is currently under development, based on feedback and results from trappers and the community.