If you’re reading this because you clicked on a social media link, this story is for you.

Before you got here, you were probably scrolling aimlessly through your feed, and somewhere between the ad for pet food, the latest celebrity scandal and a viral TikTok recipe, you saw this post, which made you stop. Maybe you liked the photo; perhaps it was the thoughtful headline, or maybe you needed something to look at during your lunch break.

In any case, it’s good you’re here. That’s because the aim of this story is to think about your social media use. Now, before you close this tab because you didn’t sign up to confront your social media habits, this isn’t going to be a guilt trip about how long you spend on your phone. In fact, it’s about whether you can do it better and how it could help our native species.

As of January this year, there were about 4.35 million active social media accounts across all platforms in Aotearoa. That sounds like a lot, but that includes people with multiple accounts, accounts for pets, businesses, charities and other groups.

Regardless, that’s still a lot of eyeballs in search of a quick laugh, meme or the latest outrage. But for conservationists and science communicators, it also represents a significant potential audience to share important stories, research, photos, videos and, in some cases, solve mysteries.

Come for the videos; stay for the science

For Dr Andrew Digby (@takapodigs), the Department of Conservation’s scientific advisor for kākāpo and takahē, Twitter is a crucial channel to expose people to the critically endangered and charismatic kākāpo.

Want to know more about the world’s weirdest birds? You’ve come to the right place. I show #conservation of #kakapo and #takahe in #NewZealand. Come for the videos; stay for the science! https://x.com/takapodigs/status/1123123443396894720

— Dr Andrew Digby (@takapodigs) April 30, 2019

“Every child in the world knows what an elephant or a lion is, but we also want them to know what a kākāpo is. Social media is an excellent way to do that,” Andrew says.

He often posts cute photos or videos of these strange and rare birds just going about their lives. Each can easily garner dozens of retweets and hundreds of likes and even generate local and international media interest. But he believes it’s essential not to just paint a rosy picture.

“Sometimes I think conservation is quite guilty of trying to tell good news stories all the time. I’m really keen that we tell the hard stuff too and show the challenges we face.”

One of those was a mysterious outbreak of aspergillosis, an infection caused by a type of fungus, among a population of kākāpo in 2019. It would eventually infect 21 birds, killing two adults and seven chicks.

“I tweeted about it and got all these messages from people around the world who research this fungus in people. As a result, we now have an international collaboration researching aspergillosis in kākāpo.

“That’s a great example of the power of social media for reaching people. There’s no way we would’ve reached them otherwise.”

Point, shoot, share

For wildlife photographer and self-confessed nature enthusiast Holly Neill (@HollyNeill), Instagram and Twitter can directly bring rare and remote species to the masses. For her, sharing photos is a chance to educate, appreciate and celebrate our native birds.

It’s also a way she feels she can give back to the birds she enjoys so much.

“I feel like I owe it to them too because I want to be able to keep taking photos of them. I don’t want them to disappear. The benefit of sharing images of our native species is emphasising the value of what we have.

“Some of my favourite moments have been when I’ve shared a photo of a species very few people seem to know about and hearing their feedback like ‘Oh my gosh, I had no idea this existed, I’m going to try find it on the weekend’.

“The shared joy that moment generates is so cool,” Holly says.

She says while some simply want to share a nice bird photo, for others, it can help spread their enthusiasm for different species and be a platform for shared discovery, learning and a free resource for information.

Spreading nature fizz

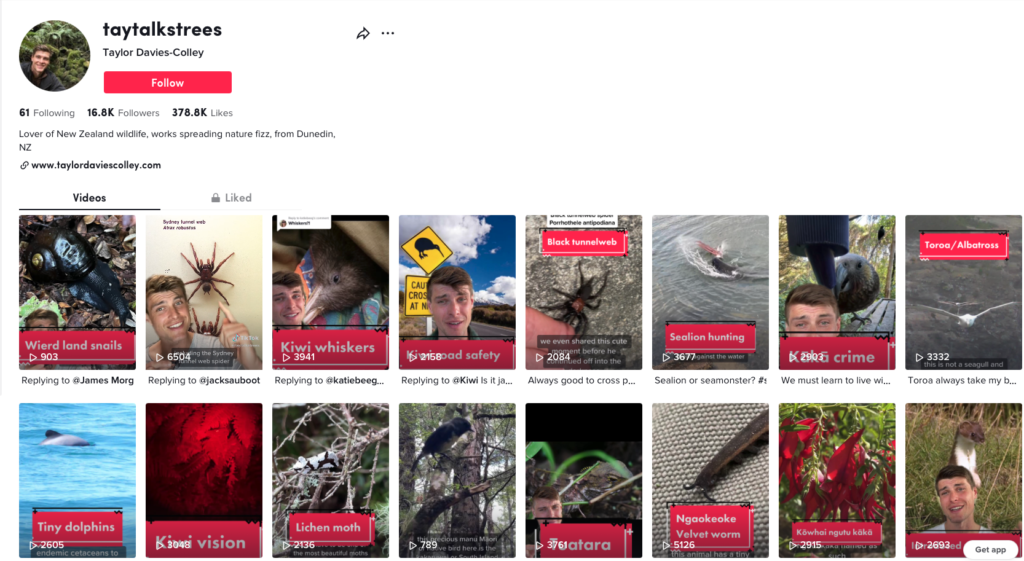

Science communicator Taylor Davies-Colley (@TayTalksTrees) also sees social media as an equaliser for getting people involved in conservation. He believes posts and videos, which show genuine excitement and enthusiasm, can make science feel more accessible.

Taylor views social media as a gateway for anyone to contribute to the conservation effort, regardless of their situation.

With his TikTok channel, he bucks the trend of pranks, stunts and dancing by uploading videos about unique native species. Fun and informative, he covers everything from ‘kiwi poos clues’ to ‘hūpiro – a plant that smells like feet’ to ‘kātipo – most venomous native spider’.

He says liking, sharing and talking to friends about posts is a free and easy way to spread conservation messages. Others may be able to donate, buy merchandise to help fund conservation work or even volunteer with organisations.

Taylor believes it’s important to highlight the different ways people can make a difference for native species.

“It’s about making those options clear and making it so people know that whatever they’re doing, it’s helping.”

Predator Free New Zealand Trust has a lot of ways to get involved in conservation. One easy way is to follow our social media accounts, but the ‘Get Involved’ page on our website has plenty of other ideas.