Melissa Boardman is an illustrator passionate about native birds, conservation and the environment. She frequently visits predator free sanctuaries across Aotearoa where she spends her time observing and photographing birds in their natural habitats.

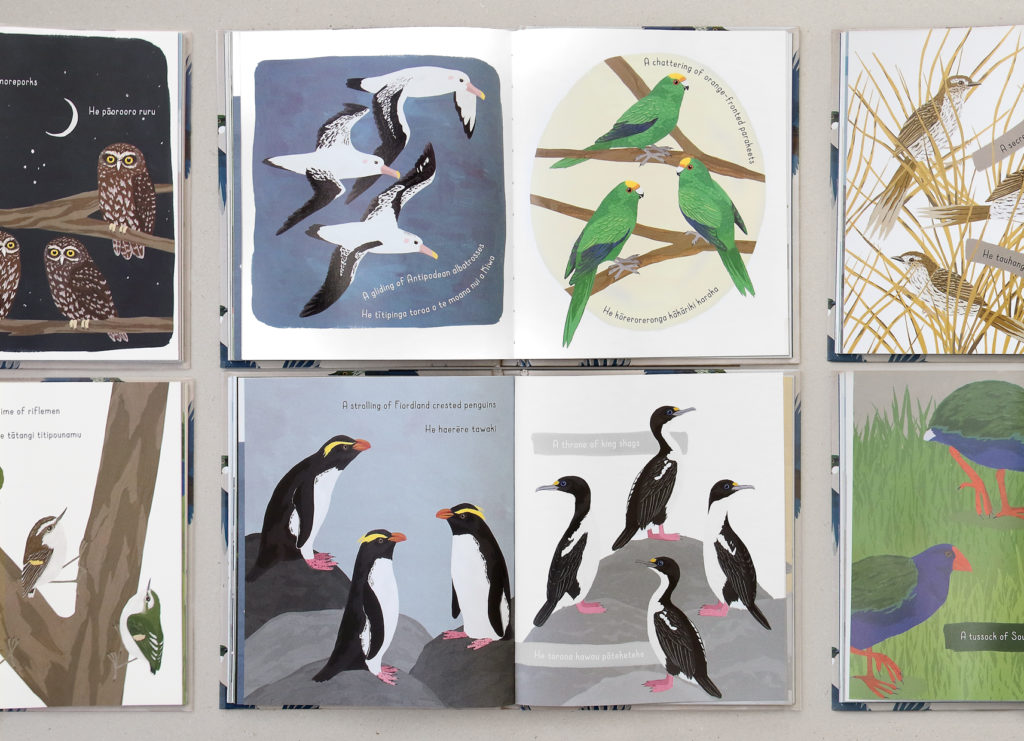

Recently, Melissa published her first book, Birds of New Zealand: Collective Nouns, a beautifully illustrated hardback featuring over 90 native bird species, accompanied by a unique collective noun.

The collective nouns used are a mixture of those already existing, those adapted from similar overseas birds, and those Melissa invented herself.

Predator Free NZ Trust was lucky enough to get to know Melissa a bit more through an exclusive interview.

Kia ora Melissa, Thank you for taking the time to answer our questions today. Firstly, congratulations on your new book. Birds of New Zealand: Collective Nouns is the first book you’ve ever published. We know you love native birds but what is the inspiration behind the use of collective nouns?

Thank you! Illustrating a book has always been a dream of mine, so it’s quite surreal that it has come true!

Collective nouns have always fascinated me, I always wondered who comes up with them and who decides they become the accepted term, so when Harper Collins contacted me asking if I wanted to write and illustrate a book about the collective nouns of native birds I jumped at the chance.

While researching for the book I discovered that many overseas birds have really great collective nouns like ‘a charm of finches’ and ‘a murder of crows’, but very few New Zealand birds had been given their own unique collective nouns. With an increasing interest in native birds within NZ, I think collective nouns are a great way to get people thinking about how birds act when they’re in groups, their relationships to one another, and whether they’re social or solitary creatures. Collective nouns are also just really fun things to talk about.

Often the collective nouns used in your book reflect something unique about the bird species. What is your favourite collective noun that you’ve used in the book and what does it say about the bird?

I’m so glad you picked up on that, the nouns were each very considered and reflect the bird in some way, whether it’s their call, their colouring or their personality.

I have many collective nouns that I’m fond of, but in particular ‘a loot of weka’ was a lightbulb moment for me. Weka are such cheeky birds and will steal your lunch if you’re not looking, so a loot of weka sums up their mischievous nature quite nicely.

‘A siren of saddlebacks’ is also a favourite, they make very loud alarm-like calls, and when a group of them are calling in unison it sounds like a siren. I’m also quite fond of ‘a chime of riflemen’, in the forest, a pair of riflemen will constantly chat to one another, their tiny gentle ‘peep’ calls seem to chime back and forth.

What sparked your passion for our native birds? Was there a particular moment or place you can recall?

It was my first visit to Zealandia Ecosanctuary back in 2009 that really sparked my interest in native birds. I remember coming face to face with a toutouwai (robin) for the first time, I felt instantly connected to the little bird and was charmed by its friendly nature. Prior to that Zealandia visit I was familiar with the common garden birds like pīwakawaka (fantails) and tauhou (silvereyes) but seeing birds like toutouwai, tīeke (saddlebacks) and hihi (stitchbirds) opened my eyes to how many amazing bird species we have in New Zealand that I didn’t know about.

After that first visit, I started researching all the birds I saw and read about how rare many of them are. It became clear that many species are struggling to survive in a country full of introduced predators and mass amounts of deforestation. It’s a sad reality for many of our native bird species but thankfully sanctuaries and predator eradication efforts are creating more safe spaces for our vulnerable native species to repopulate and flourish.

In your art you often seem to focus on our lesser-known or rarer native birds, why is that?

I feel that sharing my photographs or illustrations of our rarer birds alongside facts about them can help raise their awareness, and maybe even introduce someone to a bird they never knew about. Birds are a popular subject matter in art, but the appreciation of our native birds seems to stop at the edge of the forest. It’s a bit sad because NZ is home to a huge variety of bird species that live in other habitats, and they are just as fascinating and beautiful as our forest birds.

I feel like generally our wetland, sea and shorebirds are overlooked and aren’t respected as much as our forest birds are. As well as dealing with introduced predators like the forest birds do, they have to share their habitat and nesting sites with beachgoers, boats, vehicles and are often victims of deliberate mass killings, which is just shocking. Seabirds also have to deal with unsustainable fishery practices depleting the oceans of food, and they run the risk of getting caught in nets while out foraging, they really don’t have it easy.

Of course, I love sharing photos and illustrations of our cute forest birds, but I feel it’s important to use my platform to also talk about the overlooked birds too. I hope that by sharing my passion for our more vulnerable bird species I can inspire others to become invested in their conservation stories too.

For the Bird of the Year 2020, you campaigned hard for your first pick, the titipounamu (rifleman). What birds were your second and third picks for your vote?

Since I have such a soft spot for rare birds, my second pick was tara iti, fairy tern, our rarest native bird. There are fewer than 40 tara iti remaining so every year I reserve a vote for them. My third-place vote was a strategic vote for toroa (albatross)! Of course, I love kākāpō but I really wanted a seabird to win the 2020 election. It would have been great to raise awareness about seabirds in general and albatross are seriously incredible birds, but fair play to the moss chickens for taking out the title for the second time.

Melissa, you volunteer at Wellington’s eco-sanctuary Zealandia where you monitor the tītipounamu (rifleman) population. Have there been any stand-out moments while observing the birds?

I love every moment that I get to spend monitoring the titipounamu at Zealandia, they are such tiny birds but so full of character. I have seen a family with 4 fledglings try to intimidate a ruru (morepork), I’ve watched parent birds ambitiously try to feed their chicks food that is so big they can’t fit in their mouths, but my most favourite stand out moment was following an entire family down a track where they all bathed in a stream together.

This year has been particularly special as last year’s fledglings matured over the year and paired up to start families of their own. Some of them I have known since the first day they fledged, so to see them all grown up with their own families is pretty heartwarming. I’m looking forward to following this season’s fledglings and watching them grow up too!

Other than your time at Zealandia, where else do you like to visit to observe and photograph birds?

We’re pretty lucky in Wellington to have so many great birdwatching spots that are easy to get to. Since I live near Otari-Wilton’s Bush I visit there often and I also enjoy day trips to Waikanae Estuary as well as Mana and Kāpiti Islands.

One of my favourite spots is a few hours out of Wellington, Bushy Park Tarapuruhi. It’s an absolutely stunning sanctuary with mature forest and is great for seeing a variety of birds, especially tīeke and toutouwai. The Wairarapa Pūkaha National Wildlife Centre is great for forest birds too, especially titipounamu (rifleman). I recently spent a day at Rotokare Scenic Reserve, the amount of mātātā (fernbirds) and miromiro (tomtits) I saw blew me away, I’ll definitely be visiting again.

Are there any sanctuaries or predator-free areas around Aotearoa that are still on your bucket list to visit?

Having recently ticked Orokonui Ecosanctuary off my to-visit list, next is the Brook Waimārama Sanctuary in Nelson.

The South Island is amazing and I’d really love to spend some more time there. There are still some Islands that I’d love to visit up north too, like Little Barrier and Motutapu – to see the tūturuatu (Shore Plovers).

Although it’s not technically a predator-free area I’d love to visit the beaches where tara iti (fairy terns) reside, it would be super special to get to see our rarest birds in the wild.

I also haven’t been to Tiritiri Matangi Island for a few years so I’m really keen to go back and see the kōkako!

Aotearoa is known as the land of birds, but our country is also home to some amazing native reptiles, insects, amphibians and more. Are there any species, besides our birds, that you would like to capture in your art?

I think birds will always be my main focus, but I’m really fascinated by our native bats, I’d love to do an overnight trip somewhere to see them. Recently I’ve been learning more about skinks and geckos, and how to identify them, they are fascinating critters, but so elusive and hard to find in the wild. In comparison, birds are a much more obliging subject!

Do you have any tips for curious New Zealanders that want to see more birds in their backyard?

Planting a variety of native plants and trapping for pests are the most direct ways to benefit native birds and help create a safe space for them to visit.

A birdbath is amazing for attracting birds if you have a safe spot to put one and can commit to regularly cleaning it. I have an elevated birdbath in my garden and every day tūī and kererū use it, I’ve even had kōtare (kingfishers), kākā, tauhou, and pīwakawaka stop by. They sometimes drink from it and sometimes bathe in it, so I have to keep it very clean. The birds use it year-round, but I think they appreciate having a reliable source of clean water during the dry summer months especially. If you decide to get a birdbath just make sure to keep it clean and once the birds discover it they’ll keep coming back time and time again.

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today Melissa.

Melissa’s book can be purchased at all good bookstores or online. Her illustrations are for sale on her website.