Ian Turnbull’s father was a member of the Central Otago Lakes Branch of Forest and Bird back in 1998 when the group first began trapping in the beech forest of the Makarora Valley near Wanaka. Now Ian himself is retired and part of the dedicated trapping team.

“There were a small number of mohua left in the valley and local Forest and Bird members thought something needed to be done to try and save them,” Ian explains. “With help from the Department of Conservation they set up a couple of traplines, and it’s gone from there.”

Twenty years later, mohua are still hanging on in the valley. They’re nesting at the moment and the volunteers are making an all-out effort to try and protect them.

“The beech mast has just finished and we’ve got a rat plague at the moment,” team members report. “Each team is going out every fortnight – but we’re still losing. In the last month we’ve caught 177 rats. In the previous month we caught 130 rats compared to the normal number of about 20 rats per month. Mouse numbers aren’t particularly high and we haven’t caught a stoat for months – but we’re expecting that to change for the worse as the season goes on.”

Mohua are vulnerable to climbing ship rats and stoats as they nest in holes in old or rotten trees. Since the arrival of these introduced predators, mohua numbers have plummeted, from being the second most abundant bird in forests across the whole South Island, to just a few thousand in isolated populations.

The trapping team is up against a major problem.

“Trapping is only slowing the mohua’s decline. At the moment we’re sustainably harvesting rats along the traplines, but 200 metres up the hill rats are everywhere. The trapping is only covering a tiny part of the Makarora valley.

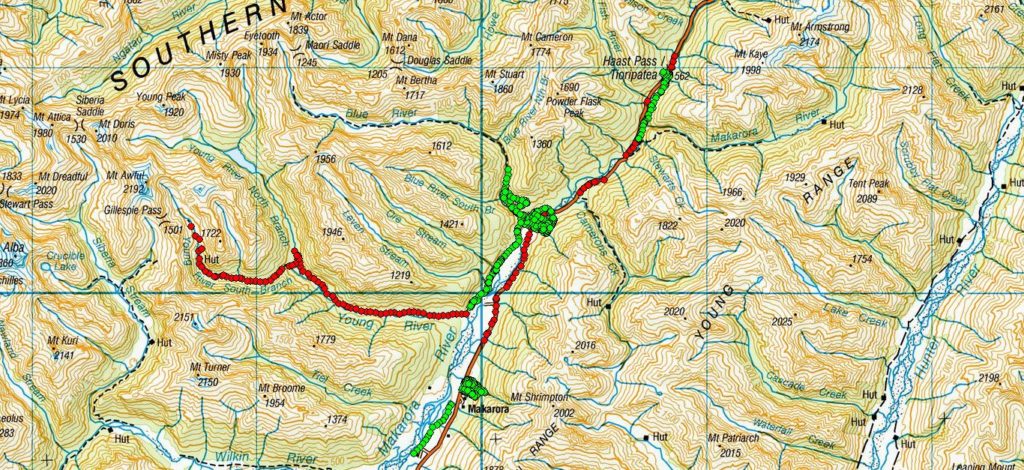

Forest and Bird’s Makarora Valley project consists of 485 rat, stoat and possum traps on 10 traplines and two close-spaced grids in the Makarora and Blue valleys. They also clear a very long (73 trap) line in the Young Valley for the Department of Conservation during the spring nesting season. No bait stations are used by the group, but, as this article is being written, DoC is undertaking another 1080 drop for the area. This can’t come too soon! Ian explains why.

“Every year since about 2009, the Mohua Trust and DOC, have put money towards an annual mohua survey. Mohua numbers were steadily declining until 2017, when 1080 was dropped at Makarora. Since then, mohua numbers have been increasing – but they’re still only back to the level they were in 2011,” he says. “DOC does a huge amount of rodent monitoring with tracking tunnels. Once numbers exceed a certain threshold, they can only handle them with 1080: our traps cannot cope and the mohua could well vanish from Makarora.”

It’s not only mohua which are vulnerable to predators in the Makarora. Kaka, kea and whio are also declining. Trapping for possums also helps protect endangered plants such as red mistletoe/pikirangi.

“We tend to get very focussed about killing things,” Ian says. “But dead rats and stoats are a means to an end. It’s actually about saving things – saving birds, and vegetation too. Without Tiakina ngā Manu (Battle for our Birds) we are struggling. We need new technologies and the group keeps in touch with new techniques and opportunities.”

Goodnature A24 and A12 self-resetting traps are now part of the trapline arsenal used at Makarora, and the Makarora trappers are meeting with Goodnature technical people to talk about how the traps are going for them.

“The traps are very well made,” Ian says, “but they also need good lures.”

In the dark, damp corners of southern beech forest valleys, even long-life lures go mouldy fairly quickly and need to be refreshed more often than the recommended ‘once every 6 months’.

Another challenge is that the practicalities of needing to regularly check DOC series and other conventional traps can limit the areas which are covered by traplines.

“The traplines have been placed primarily to suit trappers,” the team explains. “In an ideal world they’d be where concentrations of mohua are, but that’s not easily achieved. There are pockets of mohua in the Makarora that are completely unprotected and we’d like to extend the traplines over a larger area. Close-spaced grids of traps are very effective at controlling predators, but are complex to set up.”.

A recent volunteer drive has seen the Makarora Valley volunteer numbers increase from 25 to 40 people, which could also make more traplines possible.

“In non-mast years, the trapping can keep on top of predators, although more traps would help,” the trapping team says. “We’re got a really good volunteer group to work with and it’s also quite social, with teams of 2-4 people clearing a line or trap grid, then having a coffee together. We use checking the traplines to have a good time and have an outing too.”

The trap roster organiser matches the distribution of volunteers over traplines so as to suit varying experience and abilities.

“We also rotate people around the different traplines for interest,” Ian explains. “That also means that if someone can’t do their line, others can do it. And we all meet up annually for a get-together.”

For those less active but also keen to help, there are also many other support tasks to be done.

“There’s a lot to organise,” says Ian. “I call it democratic chaos! Not all the traps function as well as we’d like, for example, so we have spent a lot of time fixing older broken and rusted traps. Every month there are 28 dozen eggs and different baits and repaired traps to sort out for the trapping teams. Fundraising is needed to set up and maintain traplines and if we decide to extend our traplines into new areas, the lines have to be surveyed and cut.”

For the future, the Makarora trapping team would also like to see more coordination of trapping in the Upper Clutha area, as occurs in some other areas of Central Otago.

“Over the hill at Queenstown they have a huge number of trapping programmes. It would be good to coordinate all the little trapping groups in Upper Clutha, as happens in Queenstown, where the Wakatipu Wildlife Trust has a paid manager.”

Another aspect Ian is keen to develop is to see whether better use can be made of trapping data.

“Something which may be of interest to other trapping groups, is that we are trying to make better use of the catch records we have, going back (on some lines) as far as 2006. All our catch data goes into the DOC predator control database – another job that eats time behind the scenes. Other outfits use Trap.nz, which is similar. The obvious thing is to look at which traps catch more or fewer animals.”

“On the map, the red dots and numbers show trap locations which have caught rats over the last 7 years. We can use this to work out where to put out extra traps if we feel we aren’t keeping the numbers down,” he explains. “We plan to analyse other local factors such as vegetation, or potential denning sites, to see what is controlling predator distribution on the ground. We will then use all this information to guide optimum trap placement on new lines, or to modify existing trap networks.”

“That’s what happens when you give a retired scientist data to play with!” Ian says. “It would be very interesting to know of other groups who are doing or have done this sort of analysis.”

Like to find out more and perhaps get involved? Contact: [email protected]