Take a drive along Coromandel’s spectacular scenic 309 Road and there’s a spot, somewhere around halfway between Coromandel town and Whitianga where a tarseal street branches off from the famous winding gravel 309. A steel security gate stops the curious from venturing any further without an invitation – so what actually lies beyond?

Believe it or not, hugging the 10-kilometre private road, there’s a lush native forest subdivision. But when it was created in the late 1990s, this was a subdivision like no other in Aotearoa and 25 years later it remains a very special place. Other than the designated house sites where the 24 landowners are entitled to live, 580 hectares of steep forest habitat is protected in perpetuity by QEII covenant.

While other conservation volunteers usually have to travel to their work, Sara Smerdon – Community Advocate for Mahakirau Forest Estate Society – lives right in the environment she protects.

“It’s an extraordinary forest, rich with rarities and I can observe the seasons change and monitor the wildlife productively and easily because I live on the spot and can take advantage of the most effective times to survey, often impromptu.”

Sara and her husband bought into Mahakirau in 2009.

“We were living overseas when we bought, but have been here fulltime since 2013,” she explains. “The Mahakirau Forest Estate Society was set up in 2001 to help the 24 freehold owners pool resources and govern responsibly. Most properties are around 20 hectares and about half the landowners are now permanent residents.”

Both Hochstetter’s and Archey’s frogs live at Mahakirau, two of the three endemic New Zealand frogs, along with several gecko species including the enigmatic and Coromandel specific Northern Striped gecko and the increasingly rare Forest Ringlet butterfly.

“We live at higher altitude (semi-cloud forest) and the frogs are underfoot at our door,” Sara says. “And we can enjoy watching the Forest Ringlets out our windows. They used to be widely dispersed around New Zealand, but their habitat is under continued threat and their status is declining rapidly. A UK scientist came out in 2017 and spent 3 months searching both the North and South Islands for the Forest Ringlets. He only saw 5 –all here at Mahakirau.”

Sara and Allan, a fellow resident naturalist, took Steve out one afternoon to a spot where the butterflies could often be seen – and in fact, Sara often hosts scientific visitors and leads many of the species surveys. Sara has since monitored the Ringlet in all it’s phases – egg through to adult.

“The butterfly’s home range is small – the same as with Archey’s frogs and the Striped gecko. They are habitual and easy to read patterns from.”

Archey’s frogs are very long-lived and may spend most of their lives within the same few metres of habitat. That ought to make them easy to find, but Sara says it can take visitors quite a while to ‘get their eye in’.

“I get to know individuals’ favourite hang-outs, being fortunate enough to observe them night on night, year after year.”

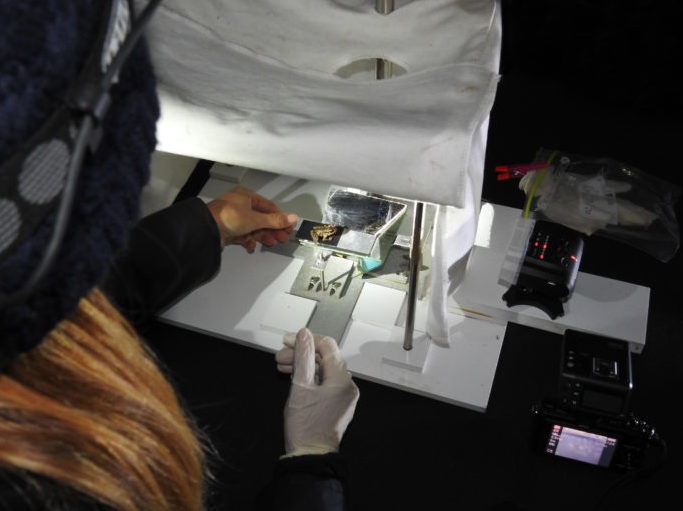

Sara works alongside Auckland Zoo developing a database at Mahakirau of individual geckos and frogs, a long-term ecological study using photographic identification, and studying aspects of their ecology and behaviour.

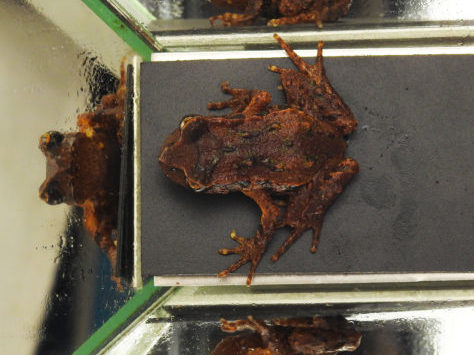

“Archey’s frogs are surveyed within a 10x10m plot annually – we are in our 5th year – and the Coromandel striped geckos are monitored each quarter over 3 or 4 nights. The frogs each have very distinguished markings, as with the geckos, the markings on the top of their head are like a unique fingerprint.”

New individuals are processed (weighed, measurements taken), climate and habitat are noted and each is photographed and catalogued.

“We photograph the frogs on a stage with mirrors to capture in one shot all features from multiple angles, front, back, sides and top down. They can all be identified by their markings, but techniques are improving, for example small microchips becoming available.”

Each frog and gecko is given a unique identifying number – but Sara also names them, creating a personal bond.

“Names are easier to remember than numbers. I try to name them according to the experience we’ve just had or a stand out feature that they posses. ‘Amnesty’ is one of our strongest breeders. We think she pairs with a gecko called ‘Wishbone’. Another male is called ‘Diamond’ whose wife is named ‘Heart’. They were two of the earliest geckos discovered and have become part of the family.”

‘Diamond’ and ‘Heart’ have been living in the same small territory dubbed ‘Geckoville’ for at least 4 years and have been seen together with offspring, usually twins, who like most New Zealand reptiles are live born.

The monitoring will help scientists and the Mahakirau community build statistics and a long-term understanding, but its early days yet to be identifying population trends. While the Mahakirau frog monitoring project has only been going for 5 years, one scientist – Professor Ben Bell – has been studying Archey’s frogs at another location on the Coromandel peninsula for 40 years.

“We know Archey’s frogs live for at least 40 years, because at least one of the frogs Prof. Bell continues to pick up in his monitoring was present the first year that research plot was surveyed. That’s extremely long lived for a frog.”

Mahakirau is a hotspot for rare wildlife. Officially named just this year, the Toropuku inexpectatus – the Northern Striped Gecko – was totally unknown to science until its discovery in 1997, when it was spotted at a Coromandel home. Today it is still considered one of the rarest New Zealand gecko species and one of the most restricted in terms of location. In an area typically well explored it was an ‘unexpected’ new discovery.

“I discovered the first on the estate in January 2015, alerted by a rustle in the leaf litter at home. In 6 years we’ve gone on to catalogue 115 individuals,” Sara says. “That’s 75% of the known population of this species, found here at Mahakirau.”

To protect such rare treasures, Sara and the Mahakirau Forest Estate Society are committed to good predator control.

“Our target focus is rats because of the particular endangered species we are protecting. Rats being the most prolific breeders, if we have them under control we know we are also on target to cater to the full suite of predators. Mahakirau has one of the most intensive control programmes on Coromandel peninsula, and we use the full toolbox available. We love data and trialling new techniques. Our goal is to keep rats under 5% throughout the year,” Sara explains. “Our latest rodent monitoring returned extraordinary results – 0.6% rats and 0% mice!”

“Our intensive pest species monitoring (rodents, mustelid and possum) is conducted 3 times per year. We currently monitor 160 tunnels and to get 0.6% detected only 1 rat. A project of this scale would normally monitor say 60 tunnels, but we want to be sure we have all information at hand to act swiftly and agile to adapt our programmes where need be.”

While rats are the focus, Mahakirau has a broad suite of predators and pests.

“Pigs are constantly reinvading,” Sara says, “particularly when there is a mast of miro berries. Luckily there’s not a deer problem on the Coromandel and despite the restraints of Covid this year our DOC funding enabled us to contract the removal of 100 goats. We are extremely cunning at catching stoats, and ferrets – having innovated trap tunnels to attract their curiosity. Roaming dogs and feral cats are also a huge threat for our kiwi.”

Wasps have also been targeted for control for the last 3 years, using Vespex.

“Wasps are a major predator of the Forest Ringlet butterfly and they’re also a Health & Safety hazard for volunteers,” Sara explains. “If you’re track-cutting and walk over a nest, one sting is enough to put their pheromone on you. You then need to run half a kilometre (in steep terrain) before they give up the chase, all the time trying to keep your heart rate down so the venom doesn’t spread!”

Mice are also a potential problem for the tiny Archey’s frogs.

“All the predators are interlinked,” says Sara. “You can’t take out just one element of the predator chain because of how they all inter-relate, but with toxin pulses alongside the trapping we’ve managed to keep the mice population down as well. No mice prints turned up on our Spring Rodent monitor, which is extraordinary!”

In the longer term, Sara and the Society would like to see now lost species returned to the protected environs of Mahakirau.

“We had for a long time just one lone male kiwi calling within our project, who went quiet in 2016,” Sara says. “However, this season we’ve monitored 7 male kiwi calling plus a female – so miraculously they’ve returned by themselves. It would be nice in the near future to replenish females for the males seeking a mate.”

“One of our driving dreams, however, is to translocate kōkako back to our forest. But we’d need expanded predator control with all our neighbours onboard. We’d need to have 2000 hectares tracking under 5% rats, as kokako are very susceptible to predation. Some even nest on the ground.”

Mahakirau currently covers only 620 hectares, so there’s work to do.

“About 75% of our boundary is Department of Conservation land,” says Sara. “While it is 10,000+ hectares the current control is aerial 1080 every 3-4 years.”

That’s not enough to control rats to under 5%. But there are good things happening on the Coromandel and project linkages are on the radar.

Other projects underway for the Mahakirau Forest Estate Society include building a Community Hub / Field Base so that visiting ecologists, students, contractors and creators would have a place to come and work, rather than needing to camp or borrow a house as they do currently.

“We’re very interested in science and building science partnerships, such as with post-graduate students,” says Sara. “The Hub will provide an education centre and we’re developing a ‘forest experience’ for local children. We can host conservation conversations and best practice workshops. We’ve raised $130,000 worth of funds and contributions, as well as huge value from in-kind labour to build this facility! It’s captured the imagination of people and engaged so much support. Heart-warming!”

It’s all a long way from the days before Mahakirau became a very unique sort of eco subdivision.

“Historically, Mahakirau was both farmed and logged, so its had a shady past,” says Sara. “Criminal even, the isolation used to grow marijuana plots. Then an application was made to set up a recreation lodge and helicopter in high paying game hunting lodge.

To their credit, the Council and Environment Court said ‘no’ to the hunting lodge concept and suggested subdivision with QEII covenant instead, the idea that multiple landowners become caretakers. While the subdivision has resulted in 24 very individual personalities, the entire estate (other than designated house sites) is under a single covenant – helping to build a special sort of neighbourhood spirit of togetherness bonded by a common purpose.

“Everyone who has bought into the estate has a deep love for nature and this is the force that connects and drives us. We all feel fortunate to live here and therefore share a deep responsibility to protect and preserve it. The forest contributes greatly to our wellbeing, and we give back. For many of us it is a forever project. A legacy we feel proud of.”

This guardianship model seems to be working rather well at Mahakirau, the first eco sanctuary of it’s kind in New Zealand.