Hester is a senior molecular technician at Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research, specialising in Ecological Genetics with a focus on Wildlife Forensics. When she’s feeling whimsical, she likes to describe her work as ‘CSI: Wildlife’.

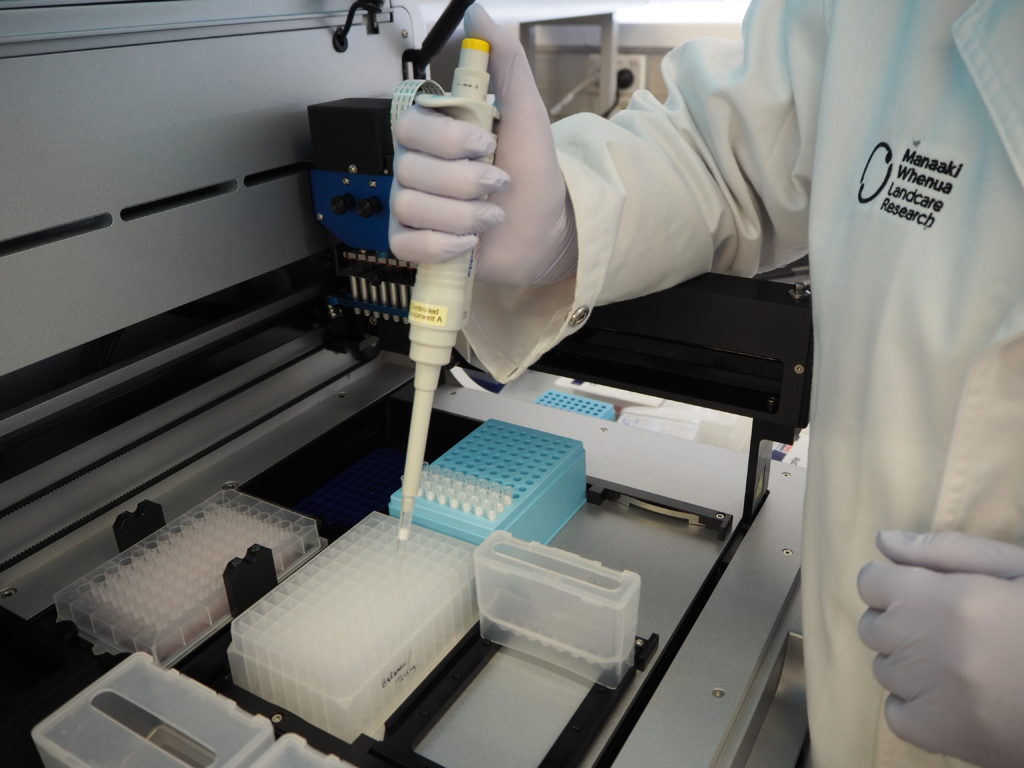

If, for example, protected species are being killed and the predator responsible needs to be identified, then Hester can help. She is part of EcoGene®, a small business unit within Manaaki Whenua that provides DNA diagnostic services. Unlike crime television series, however, the ‘CSI: Wildlife’ team don’t usually investigate the actual crime scene themselves.

“We do a lot of work with the Department of Conservation and protected wildlife,” Hester says, “And also for a number of councils, using DNA to investigate attacks on stock and domestic animals for example.”

“A ranger might find a dead kiwi and wonder if it’s been predated. They would ideally take a photograph of the body in situ, look at the area for entrails or feathers spread around, collect the whole body and refrigerate or freeze it in a sterile plastic bag – then courier it to us overnight. Alternatively, they might send it to Wildbase at Massey University first for necropsy and Wildbase would send on the swabs. If the ranger has been trained in forensics, they might take the DNA swabs in situ – swabbing wounds, damp patches (potential saliva slobber), under claws if the victim has fought back.”

Hester and the team at EcoGene® often work in conjunction with Wildbase on protected wildlife cases. “DOC will then work with both of us to understand what happened”

DNA is like a molecular fingerprint –it is unique to each individual and, just like in human crime forensics, DNA from a single predator can be used to identify that particular animal.

“This testing can also be brought to bear in legal cases. Prosecutions under the Wildlife Act and the Dog Control Act for instance may require DNA evidence, and we provide testing services and expert witness statements.

“The aim is to make an individual ID, but that can be pricey and time-consuming,” Hester explains. Sometimes identifying the individual responsible for a killing isn’t necessary – it’s the species of predator that needs to be identified so that control strategies can be tailored to that particular type of predator. DNA samples for analysis often come from saliva around bite wounds – so generous amounts of slobber is important and helpful – as is a good, fresh corpse.

“Fresh is best,” says Hester. “If someone is interested in getting forensic DNA testing done, they should talk to us first to see if it’s worth doing. For example, we can struggle to recover the predator’s DNA evidence if there is a lot of insect activity.”

“If wildlife are being predated on an offshore island, is it a bird or a mammal that’s responsible? It’s a lot harder to identify a predatory bird from DNA,” Hester admits. “Maybe because they’re a lot less slobbery!”.

Identifying the predator has big implications for pest control and informs adaptive management strategies.

“For instance, there was a case where kiwi were being killed by ferrets. We found evidence that suggested it may have been one specific ferret that killed multiple kiwi, which shows the amount of damage one rogue animal can do. This DNA evidence resulted in targeted ferret control for that region.”

“We also have specific tests developed inhouse for all the mammals present in New Zealand, except bats, which makes mammal DNA much easier to test. We can therefore test for pigs, stoats, ferrets… and build up a possible sequence of events. It’s important to consider whether the animal we’ve detected was the predator, or a scavenger, so necropsy can help to determine primary cause of death.”

While an individual’s nuclear DNA is unique, cells also contain mitochondrial DNA which shows much less variation but can be used to make identifications at species level.

“Mitochondrial DNA is present in cells in much higher copy numbers,” Hester explains. “In the nucleus of mammalian cells there are only two copies of the DNA of every gene – typically one from the mother and one from the father, but within each cell, there can be thousands of mitochondria. Because there’s so much more mitochondrial DNA, it’s easier to find it in degraded samples. Mitochondrial DNA is passed down only through the maternal line, so it is no good for identifying individuals, but it’s perfect for species.”

Wildlife forensics is a useful tool in a wide range of situations. Not all the ‘wildlife crimes’ Hester deals with involve animals found in New Zealand.

“We also do testing on products of unknown provenance that are suspected of being in violation of CITES – The UN Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. If a carving intercepted at the border is suspected of being from elephant ivory, we can get a species ID from a very small sample,” Hester says. “We sample the item in the least destructive way possible and collect DNA,” she adds.

In fact, the only species Hester doesn’t study genetically are humans. She undertakes research across a range of species for a variety of purposes “Part of my research also involves developing genetic tools for ecology that can end up being provided as a service by EcoGene®,” she explains.

“At Manaaki Whenua and the Ecological Genetics Lab we work with fungi, bacteria, plant pathogens… There’s a lot of insect work, for example research on insect adaptation and strategies for climate change. We do a lot of taxonomy identification and evolutionary work too. Manaaki Whenua houses the National Arthropod Collection with 6.5 million specimens, the National Fungal and Plant Disease Collection with 95,000 dried specimens and the International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants with 20,000 live fungi and bacteria, as well as the New Zealand Fungi and Bacteria Database.”

Work in wildlife forensics and ecological genetics is certainly varied and revealing, although possibly not for the squeamish.

“We do receive a lot of poo in the post!” says Hester.