Gerald Dickinson has a busy year ahead. He’s just won a WWF Innovation Award for his Grid-i pest-detection development project and is aiming to have commercial units available by December 2018. It is – he freely admits – an ambitious timeline.

“The Innovation Award is a huge boost,” Gerald says. “The various hardware components are available, but I need to write the software that will glue it all together.”

So what is Grid-i?

“It uses modern technology to detect and identify invasive mammals,” Gerald explains. “A low-resolution sensor reads the thermal heat signature of the animal. The heat signature is slightly different between different species. The software will detect whether it is a possum, stoat or rat. It’s a bit like recognising a face. There are big features and also little features that define that face. So we are determining what big features are required.”

At the moment Gerald is working with Bruce Warburton’s team at Landcare Research, Lincoln to determine what level of data is needed to reliably identify the key predator species. They have built a data recording tool to record thermal and video data in low-resolution onto an SD -card.

“After forming the new business called iDetect-IT, the aim is to get enough data for identification, but not too much data,” Gerald says. “I approached Landcare Research about using recording devices in their animal pens. We’ve set up the test tools in the animal pens and we’re in the middle of collecting thermal and video data. So far we’ve done possums and stoats and rats are next. There are 3 pens with 3 recording devices set up – the low resolution (video) recorder, a thermal device recording the heat signature and a standard high resolution infra-red device that can see in pitch black. The 3 devices are gathering data which we will then compare and correlate between.”

The aim is to:

• Determine if different target species have different heat profiles;

• Determine if target species can be identified remotely using thermal imaging;

• Determine if thermal data resolution from thermal sensor is enough to distinguish species.

And that’s just the beginning of Gerald’s work-plan for 2018. The next stages are:

• Analyses heat-signature data from the 3 targets (requires building PC based tools to analyse the data);

• Develop heat signature template library of the 3 species;

• Incorporate template library into working software operating on embedded processor;

• Develop AI (artificial intelligence) software utilising template library to extract key features from raw thermal data and detect target presence;

• Build prototypes (unit with battery) to test in home urban environment around a compost heap for rat activity;

• Expand prototype trial into wider area (with help from Ngaio Predator Free trapping group);

• Commercial units December 2018.

Phew! That’s a lot to pack into the next 11 months.

“Analysing the data will be the interesting part,” says Gerald. “There are no software tools to analyse so I’ll be building up software test tools in ‘Python’. It’s a software language that allows you to do big number crunching on a home PC with good memory. Then I’ll be able to load in data files and process the data for information, by filtering out the unwanted and enhancing the wanted, you get more useful information.”

Gerald likens the process to using something like ‘Photoshop’ by using sharpening filters to fix a blurred image.

“This is the key to the design, having an efficient algorithm extracting useful information. The benefit is the software can operate in a lean and mean state with no unwanted features. This reduces the need to have a powerful processor or operate the processor at a slower speed. A faster operating processor uses more power. By improving the software efficiency, it improves the battery life.”

With a background of 20-25 years in electronic software design in private industry, Gerald is clear about his key requirements for the final product.

“Grid-i needs to have a long battery life (many weeks), be robust for the outside environment and be reliable with a high degree of accuracy,” he says.

Those priorities were developed when Gerald was developing embedded software devices for the military such as bomb disposal work in Afghanistan.

“I was building devices with a transmitter and a receiver. The receiver was put next to a detonator. The transmitter at a safe distance sent a “blow up now” message to the receiver. The devices had to be robust (with bombs detonating nearby!) and very safe. So I learnt to build rugged, long-lasting devices with a long battery life. They needed to go when you wanted them to ALL of the time.”

Gerald is also aiming to make the devices affordable so that it is feasible to have multiple units forming a ‘grid’ information picture of predators – for example with each house in an urban environment having one unit.

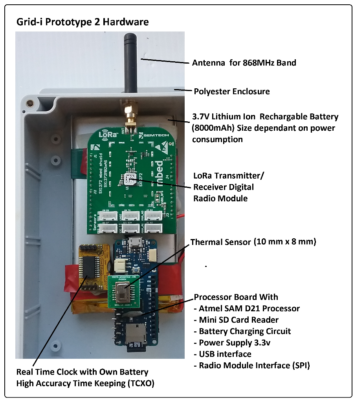

“They should be commercially available for $200-$250 per unit,” he says. “The product will look like a ‘fat cellphone’. It will be a ‘surveillance box’ with a battery, electronics and software aboard and it will be a sensor. It won’t have a display. Devices will record and detect anything in their field of vision (eg ‘rat’ at 0300 hrs located at address ) and will be able to ‘talk’ to each other. A central data repository will collect the data (what is where) from the individual devices.”

Gerald will also be building applications that will pull out the data to a website-based display. The grid of devices will show what is happening, where it is happening and how it changes over time (eg seasonal differences or trapping programme effectiveness).

“What makes it so interesting, is knowing that it can be done, but not knowing how,” says Gerald, who clearly likes a challenge. “It’s about solving problems so that things can be done efficiently.”

He’s looking forward to testing prototypes in his compost heap later this year.

“In the real world things happen that you’re not expecting,” he says. “Grid-i has many potential applications. This technology will help backyard trappers in the war on urban pests, so we can see the return of our native species into our cities. These intelligent devices (with machine learning, AI algorithms) would be beneficial for conservation operations by helping target specific species more accurately and moving away from current indiscriminate pest removal methods (eg 1080). Grid-i also has great potential for eradication operations to locate and remove the last 1% of difficult pests from an area in the move towards a Predator Free New Zealand.”