Feral cats live on every continent except Antarctica – surviving in deserts, forests, farms, and cities. But even though they can live almost anywhere, some habitats are more appealing than others.

New research published in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology found that landscape type might play a role in how far feral cats wander. With wild cat populations on the rise here in Aotearoa New Zealand, understanding how they interact with different habitats will help us figure out how best to tackle the issue.

We caught up with Cathy Nottingham, the PhD student behind the study, and asked her what this research might mean for the future of feral cat management.

What’s feral about feral cats?

A feral cat is not a domestic cat. While a house cat is fed and looked after by humans, a feral cat is independent of people. To survive, feral cats hunt a wide range of animals, adapting their diet to suit their habitat.

“Feral cats are opportunistic hunters and will eat what they find,” says Cathy. “They can be particularly devastating for birdlife.”

She’s quick to add that it’s not just birds that suffer but also lizards, eels, wētā, and bats.

As well as being devastatingly good hunters, wild felines can carry dangerous diseases such as toxoplasmosis. They pass this potentially deadly infection on to farm animals, native birds, and even dolphins through contaminated faeces.

As feral cat numbers climb, the threat to our precious native fauna also increases.

Forests, food and frisky felines

To find out which habitats tend to have larger populations of feral cats, Cathy reviewed research from around the world. She found that a feral cat’s home range depends on various factors such as food availability, land use, competition, sex, and age.

“There is a lot of variation in feral cat home range sizes, and it seems to vary between habitat types,” she says. “In an urban area, you might get home range sizes of about nine hectares, whereas, in an arid habitat like those in Australia, you could get one cat ranging about 3,000 hectares.”

That’s the equivalent of about 3,000 rugby fields.

Whether the cat is male or female also influences how far it might travel.

“I found that males had a bigger home range size than females, in general,” Cathy says. “While male cats might travel far in search of a mate, a female is concentrated on getting enough to eat and finding shelter for raising offspring.”

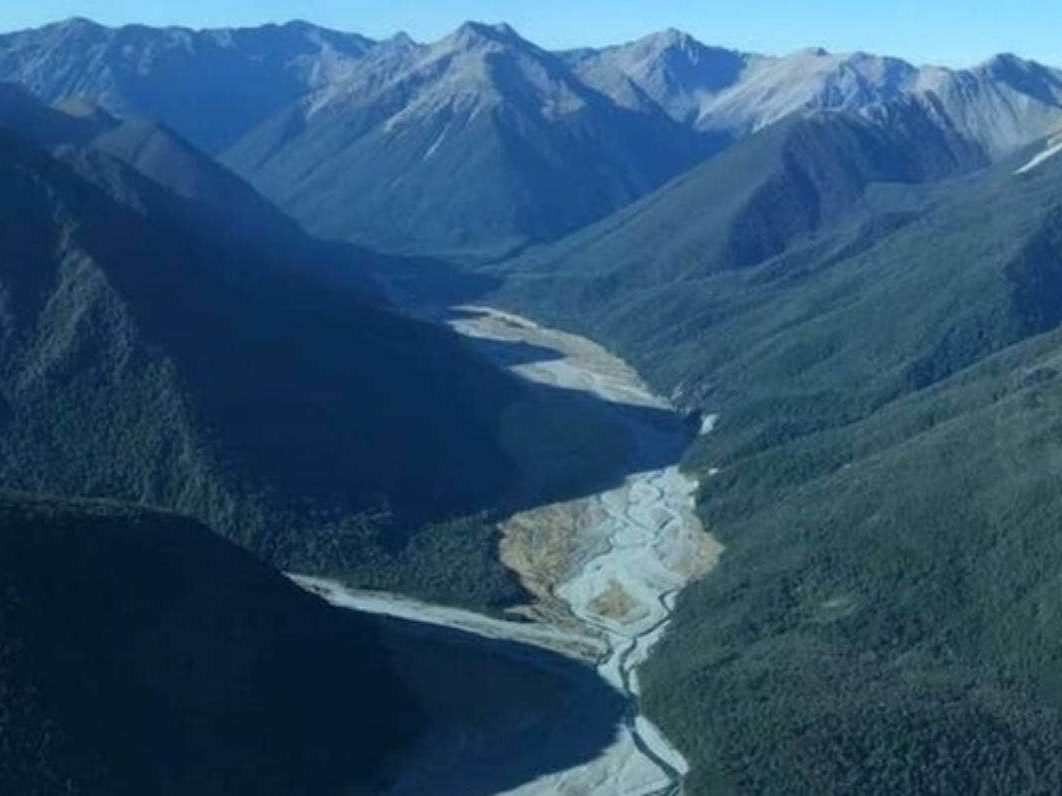

Feral cats can travel seriously long distances. For example, scientists in the South Island high country tracked a feral cat that travelled almost six kilometres in one night. At the same time, another study found that feral cats are now crossing the Southern Alps via high-alpine passes.

Cathy also found that feral cats seemed to prefer forested areas to open pastures. This is because forests offer shelter from the weather, places to hide, and are home to plenty of prey.

Studies like this contribute to a growing picture of where feral cats live and their preferences.

“Having a good idea of the home range will help manage feral cat populations. For example, knowing roughly how large home ranges are in a particular habitat type will help tell us how far apart to place traps,” Cathy says.

Feral cats on farms

For the next part of her PhD, Cathy focussed on one of the most significant land types here in Aotearoa New Zealand – farms. Around 40% of land in New Zealand is farmland, while national parks and conservation areas make up about 30% of the total land.

Because farms cover so much of the country, understanding how feral cats interact with farmland is vital if we want to protect our native wildlife. And Cathy says, “reducing feral cat numbers is beneficial for farmers because of the risk of toxoplasmosis to farm animals.”

Many farms throughout the country also plant lots of native vegetation to manage erosion or create shelter. However, with feral cats preferring tree cover to open pasture, Cathy predicts that increased plantings will also impact cat populations.

For her research, Cathy caught and collared fourteen feral cats living on farms north of Auckland. She kept track of them for up to thirteen weeks to find out how far they were roaming and what kinds of habitats they preferred.

Results from this part of her research haven’t been published yet, but we’re looking forward to hearing more about what she found in the future.

Want to help?

Cat owners have an essential role to play in the predator free movement and in conserving our unique and beautiful wildlife.

Take this quick quiz to find out if your cat is conservation friendly.

You can find handy tips for keeping you, your cat, and your backyard birds safe and happy here.