Could moa have once lived on Rakiura/Stewart Island? Moa bones have been found on Rakiura in the past, but nearly all of them have shown signs of butchering and been found in ancient Māori middens. They’ve mostly been major leg bones (the meatier part of moa) and could easily have been transported across Foveaux Strait for a feast – Aotearoa’s earliest ‘chicken takeouts’ if you like.

Science has had little to say about moa actually living on Rakiura up until now. But researchers Alexander Verry, Matthew Schmidt and Nicolas Rawlence from the University of Otago Palaeogenetics Laboratory and Department of Conservation’s Dunedin office put the case for moa living locally in a paper just published in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology. They base their evidence on a recently discovered skeleton, found on a remote part of Rakiura, of a large moa which almost certainly died of natural causes. It showed no signs of butchering or any other human associations.

“In March 2020 AJFV and MS travelled to West Ruggedy Beach to excavate a moa skeleton with the aid of Phred Dobbins (Department of Conservation). The skeleton was found c. 500 metres inland from the coast at the northern end of West Ruggedy Beach, resting within an eroded depression in a large granite boulder. The moa remains had been protected through lying in this granite ‘bowl’ and covered in pure quartz sand. Recent storm events had stripped the old dune system down to its underlying granite base exposing the moa remains.”

Crucially there was no evidence of the skeleton being associated with any cultural event or activity such as charcoal or stone tools.

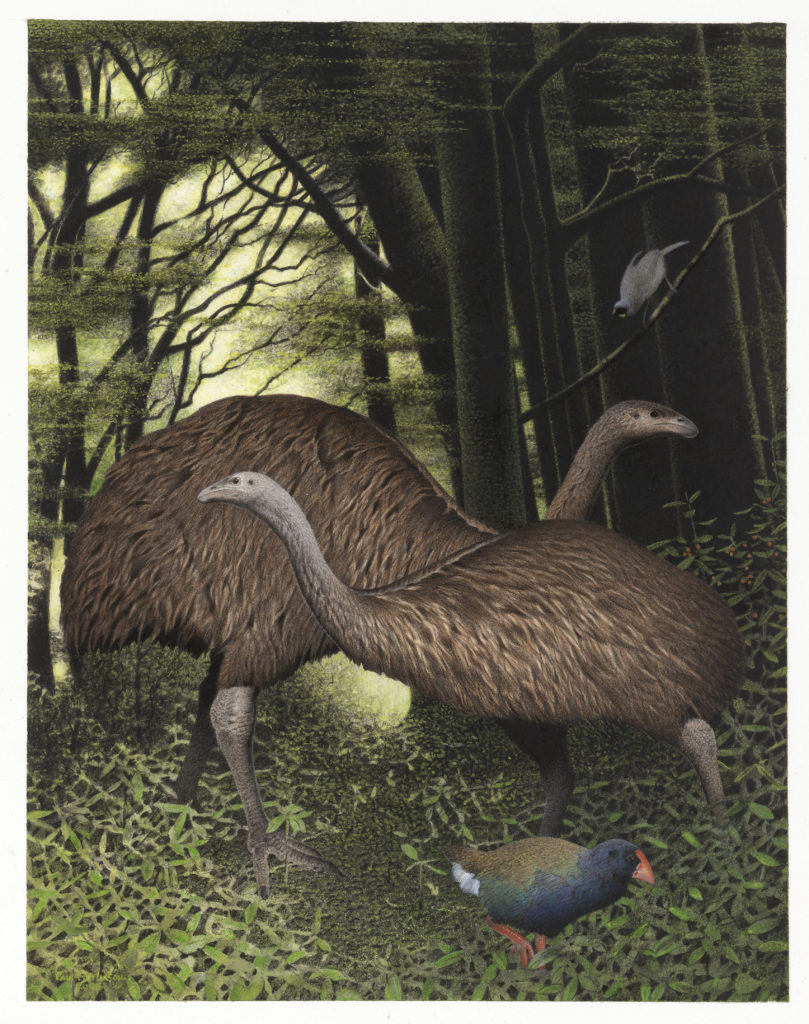

“Prior to human arrival (c. 1280 AD), moa were found throughout the North and South Islands, with six species represented in the Late Quaternary avifauna of the southern South Island: South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus), upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus), heavy-footed moa (Pachyornis elephantopus), stout-legged moa (Euryapteryx curtus), eastern moa (Emeus crassus) and little bush moa (Anomalopteryx didiformis). Anthropogenic pressures such as hunting and habitat destruction drove the moa to extinction within 200 years of human settlement and many moa bones can be found in early Māori (c. 1280–1450 CE) middens, where almost all of the moa material known from Rakiura is recorded.”

Could some of the moa species living in the South Island, have also been present on Stewart Island? Moa couldn’t fly across Foveaux Strait and it’s difficult to imagine them being strong swimmers either. But then, sea levels weren’t always the same as they are now.

“During Pleistocene glacial periods, Rakiura would have been connected to the South Island as sea levels were 120 m lower than present. As a result, the pre-human Rakiura avifauna was likely similar to that of the southern South Island. However, knowledge of Rakiura’s prehuman avifauna may be biased towards certain taxa due to the limited types of local bone deposits (e.g. sand dunes) compared to extensive cave systems and non-acidic swamps which often preserve Late Quaternary subfossils. Of particular note is the lack of moa remains in the majority of subfossil sites on the island.”

Moa were definitely eaten on Rakiura however.

“Isolated moa bones morphologically identified as eastern moa, stout-legged moa, and South Island giant moa, are common within the Rakiura midden sites at The Neck. It has been proposed that these remains may have been transported from the South Island, as major leg bones (femora, tibiotarsi and tarsometatarsi) make up the vast majority of moa remains found within this site.”

“Archaeological excavations and surveys of moa hunting sites have found that such assemblages (e.g. Shag River Mouth, Pleasant River Mouth and Waitaki River Mouth) are dominated by moa leg bones; leg bones contain most of the meat and were therefore more often brought back to settlements after a kill. As a result, transportation of moa legs from kill sites around Rakiura to sites such as those found at The Neck, cannot be ruled out.”

So what made the latest moa find so interesting? Well for a start there was a lot more than just leg bones present.

“We excavated the skeleton and collected at least eight different elements, including partial left and right tibiotarsus (left shaft fragments and right shaft), right femoral shaft, heavily fragmented pelvis (including sacrum, illium and ischium, left and right acetabulum i.e. femoral sockets), a single thoracic vertebra, partial rib bones, and several unidentifiable bone fragments. A single, isolated left femur (the same size and dimensions as the right femoral shaft) was found on the dune surface, approximately 20 metres from the skeleton, likely belonging to the same individual. It is probable that the crania, vertebrae, tarsometarsi, and phalanges were blown or eroded away.”

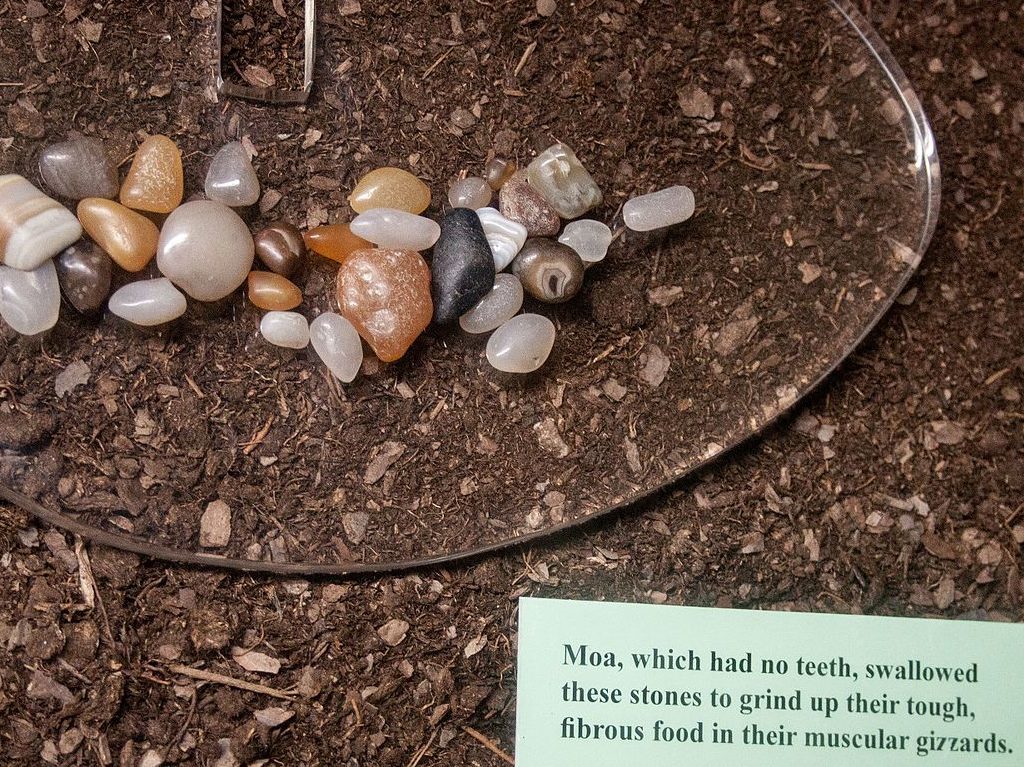

“Associated gizzard stones were discovered underneath the pelvis in a small tight group, and a dark brown organic-rich layer of sand was found immediately surrounding and underneath the remains. While there is exposed granite in the area, the majority is covered in pure quartz sand, making it improbable that the gizzard stones could represent eroded pebbles that concentrated underneath the pelvis. At West Ruggedy Beach there are patchily distributed organic-rich layers that no doubt represent decomposed plant material as a result of dune movement. However, the depositional setting of this moa skeleton (within a granite bowl surrounded by pure quartz sand) suggests this concentrated organic-rich layer originated from the decomposing moa and gizzard contents.”

All of which means there was good evidence that an entire individual moa had died and decomposed at the site.

“Analysis of the bones did not reveal any butchering marks which may have indicated the moa was killed and processed by humans. Furthermore, the presence of a partial skeleton, associated gizzard stones and organic-rich layer lends support to the hypothesis that the death of this moa was due to natural causes but does not completely rule out the hypothesis this individual was killed by humans and/or transported to the site.”

The researchers then used radiocarbon dating and ancient DNA analyses to determine the age and taxonomic identity of the specimen.

“A 1 cubic centimetre cortical bone sample was taken from the partial right tibiotarsus using a Dremel cutting tool. A sub-sample of 0.5 cubic centimetre was sent to the Waikato Radiocarbon Dating Laboratory (University of Waikato) for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating, while the remainder was transferred to the Otago Palaeogenetics Laboratory (University of Otago) for ancient DNA analysis. The Otago Palaeogenetics Laboratory is dedicated to the manipulation of ancient DNA, physically isolated from other molecular laboratories, and undergoes regular decontamination with bleach (sodium hypochlorite) and UV irradiation.”

Results from this ancient DNA analysis showed that the moa skeleton found at West Ruggedy Beach was that of a South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus).

“The closest genetic match to the consensus sequence (GenBank accession number: OK077991) obtained from this specimen is that of a South Island giant moa from Glendhu Bay, Wanaka with 99.7% sequence similarity (1 base pair difference along the 378 bp of comparable sequence). The absence of a femoral neck on the isolated left femur is consistent with this identification.”

Time period-wise, the moa skeleton overlaps with the time when humans first occupied Stewart Island.

“The West Ruggedy Beach moa skeleton was dated to 672 ± 20 yrs BP (before present), corresponding to 1297–1395 CE, within the time period of the early human occupation of Rakiura. The discovery of a partial South Island giant moa skeleton on Rakiura dating to shortly after human colonisation of the area represents an important contribution to our knowledge of the avifauna of the islands soon after human arrival.”

“The presence of a dark organic-rich layer immediately surrounding and underneath the remains, alongside associated gizzard stones found underneath the pelvis, indicate that the moa likely died near to where it was discovered and was not transported to the site. The depositional setting and nature of the skeleton is similar to the natural pre-human South Island giant moa discovered at Native Island and unlike the isolated legs bones of Dinornis, Emeus and Euryapteryx individuals from The Neck midden.”

So what might Rakiura have been like, in the time period when moa lived there? Which of the six South Island moa species might have been present?

“Of the six moa species known to inhabit the southern South Island, only the generalist South Island giant and open shrubland/grassland specialist heavy-footed moa may have occurred naturally on Rakiura. The island was connected to the southern South Island during the last glacial period but became isolated due to sea level rise c. 10 000 years ago.”

Studies of ancient pollen have also shown that Stewart Island’s plantscape was markedly different in ancient times, compared to the forest species now thriving there.

“Pollen data from coastal Southland suggests that the glacial (> 11 700 years ago) habitats on Rakiura were dominated by grasslands, which could have supported heavy-footed, stout-legged, eastern and South Island giant moa populations – the former three species dominate glacial subfossil deposits in Southland, and at least heavy-footed and eastern moa had refugial populations in the area. It is entirely conceivable that little bush and upland moa, whose preferred habitats were closed canopy forest and subalpine areas, respectively, were not present on Rakiura by the time Foveaux Strait was flooded by rising sea levels, despite the presence of upland moa at low altitudes in Southland during the last glacial period.”

“The oldest pollen records on Rakiura, dating back to the Pleistocene-Holocene transition c. 11 600 years ago, show that the area was covered in scrub, ground ferns, tree ferns and rātā, with forest only becoming a feature of the landscape 9000 years ago. Initially dominated by kāmahi and southern rātā, this was followed by a change to predominantly rimu and miro forest around 5000 years ago.”

Not all moa species would have welcomed the changing habitat.

“The common South Island giant moa would have been able to live within this forested landscape. In contrast, stout-legged, eastern, and heavy-footed moa, who prefer more open habitat would have been pushed into dune habitats; these four species dominate late Holocene dune fossil assemblages in coastal Southland. In contrast to these mainland dune deposits, where moa remains are common, they are rare (with the exception of The Neck) in Rakiura dune deposits (which are dominated by seabirds with the near absence of forest birds), suggesting moa occurred at low population densities on the island.”

So Rakiura had moa – but probably not many of them.

“Our research supports the hypothesis that the South Island giant moa skeleton recovered from West Ruggedy Beach likely originates from a natural deposit. At least this species, and potentially heavy-footed moa, may have occurred naturally on Rakiura at the time of Polynesian arrival. Other moa species may also have occurred there, albeit at low population densities, based on available habitat. Future subfossil discoveries (including extensive and systematic excavations of sand dune, rockshelter and cave deposits), and genetic and geochemical analyses of moa bones and gizzard stones (e.g. oxygen and strontium isotopes) to determine local versus transported origins, may shed further light on the pre-human avifauna of Rakiura.”

FULL ARTICLE: A partial skeleton provides evidence for the former occurrence of moa populations on Rakiura Stewart Island (2022). NZ Journal of Ecology