Why are some native species so much harder to save? Kelly Hare et al have called them the ‘intractable species’ and investigate why they continue to flounder even with rigorous conservation efforts in some cases.

The authors look at 7 case studies to try and identify what’s going on and what else we might need to do to help those birds, insects, dolphins and others. Their study is published in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand.

“Here we ask whether commonalities exist among New Zealand taxa that could be termed conservation ‘losers’, either because they have been largely ignored by managers or because they have been resistant to management efforts – collectively, intractable species.”

The authors look at a wide diversity of plants and native organisms and ask the same questions about each.

- Why was the focal species chosen?

- What conservation actions have taken place to date and what was the outcome?

- Are these taxa dependent on ongoing conservation action and what are their prospects for the next 30 years?

“In choosing our case studies, we aimed for a breadth of scenarios, rather than representative species from every taxon and habitat type. Our studies come from marine, aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, covering a variety of conservation issues and complex, and perhaps unsolvable, problems.”

The authors use both the IUCN Red-list and the New Zealand Threat Classification System to assess the current state of each species.

“In an attempt to understand the extent of the biodiversity crisis in New Zealand, DOC developed the NZ Threat Classification System (NZTCS). The NZTCS, in use since 2011 and assessed over a 5 year cycle, complements the IUCN Red-list (IUCN 2017), but provides greater sensitivity to circumstances unique to New Zealand (e.g. historically isolated populations), and has been used to set priorities for funding from the New Zealand Government to conservation agencies.”

The 7 case studies are:

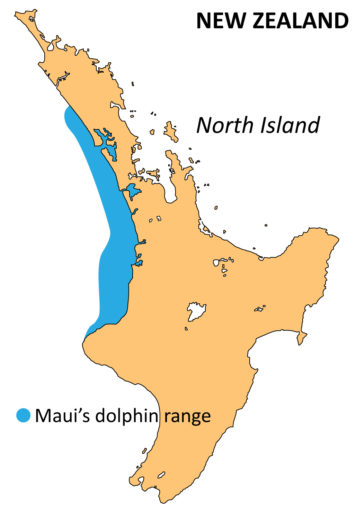

Māui dolphins

“Māui dolphins are endemic and restricted to the west coast of the North Island, where they are the only resident coastal dolphin. Taxonomically, they are a small, remnant population, genetically distinct from Hector’s dolphins of the South Island and managed as a separate conservation unit. As a top predator, they likely once played an important role in the coastal ecosystem. They are the rarest marine dolphin in the world, with only 63 individuals over 1 year of age.”

Māui dolphins are ranked as ‘Critically Endangered’ by the IUCN Red-list and ‘Nationally Critical’ using the NZTCS.

“During the late 1980s and 1990s, declines were attributed to the unsustainable rates of gillnet bycatch, with urgent calls for action to save the Māui subspecies after its genetic identification. However, years of legal action and delays in implementing protection resulted in continued decline during the 1990s and 2000s, with the population estimated to have been reduced to as few as 55 individuals at one point. In 2008, a sanctuary encompassing the core range was established and further extended in 2013. This sanctuary banned gillnets and limited trawl fisheries, but is unable to mitigate threats from toxoplasmosis and natural predation from sharks.”

The future of Māui dolphins is uncertain, the authors concede.

“Innovative survey methods are being developed to enable year-round monitoring, but despite improvements in monitoring, numbers remain critically low, and stakeholders still struggle to coordinate conservation actions.”

Toanui/flesh-footed shearwater

“Toanui are medium-sized (∼700 g), wide-ranging, apex predators that forage mainly on fish and squid in the Indian and Pacific Oceans and migrate to Japanese waters during the Austral winter. Due to declining numbers for over 40% of global populations (total population about 74,000 pairs), toanui are listed as ‘Near Threatened’ by the IUCN Red-list (IUCN 2017) and ‘Nationally Vulnerable’ under NZTCS.”

Toanui face threats from predators on land, as well as habitat loss and harvesting. Threats at sea include fisheries bycatch, pollution and climate change). Despite conservation actions across jurisdictions, they are still declining

“New Zealand populations (16% of the global population) breed at about 15 sites from northern NZ to Cook Strait, but are declining. At least four colonies have disappeared since surveys began in the 1930s. The main drivers of the decline in NZ were initially assumed to be invasive mammalian predators and over-harvesting of chicks from burrows. However, the population on Tītī Island, Cook Strait, continues to decline despite cessation of legal cultural harvest and eradication of Norway rats in the 1970s.”

Many of the threats are human induced, including plastic ingestion.

“Fisheries remain a consistent threat to toanui which are classified as being at ‘high risk’ of being caught by recreational and commercial fishing activities in New Zealand. Furthermore, stable isotope analyses suggest either spatial shifts or reduced availability of prey of toanui. Finally, plastic ingestion is associated with population declines through reduced reproductive fitness and mortality of adults and chicks.”

Plastics have been found in digestive tracts and burrows of toanui on Ohinau Island, Hauraki Gulf and in 90% of chicks on Lord Howe Island.

“Despite the use of fisheries bycatch mitigation methods in Australian fisheries and eradications of invasive predators on breeding islands in NZ, toanui are predicted to continue to decline by as much as 50% (to ∼37,000 pairs) by 2050. Effective conservation action may be achieved by expanding global co-operation on fisheries bycatch mitigation, reducing marine plastic pollution and eradicating invasive terrestrial predators from breeding sites in other parts of the world. In NZ, toanui have historically been relatively low priority for conservation funding and this may need to change.”

Pīngao/golden sand sedge

“Like many endemic NZ plant species, pīngao (pīkao) are declining through habitat loss, weed invasion and habitat degradation. Pīngao grows in coastal ecosystems nation-wide and are a treasured source of fibre for weaving and art.”

Human-induced habitat loss is a big issue for pīngao conservation.

“The ecosystems that pīngao create have been reduced and degraded by past anthropogenic factors, including fire, land clearance and development for human habitation, agriculture and forestry. Throughout the twentieth century, much government money and many person-hours were devoted to stabilisation of coastal areas by planting dunes with invasive plant species, such as marram grass, tree lupin and pine trees, all of which are now significant competitors of pīngao.”

Vehicles and foot traffic along with introduced mammal herbivores also impact the plants. Predicted sea level rises and increased severity of storms are future threats likely to reduce suitable habitat.

“Despite considerable public attention and value as a taonga, pīngao continue to decline. Without major changes in coastal land-use, coupled with restoration and weed control to recreate and rehabilitate sand dune systems, pīngao may not be able to recover.”

Kākahi/freshwater mussels

“New Zealand has three recognised extant species of kākahi which are considered ‘Threatened’ or ‘At Risk’ in the NZTCS and ‘Data Deficient’ or ‘Least Concern’ by the IUCN Red-List. The most widespread species, Echyridella menziesii, is found in lakes and waterways throughout the country and is declining (e.g. Whanganui River). Echyridella onekaka, a poorly known species difficult to distinguish from E. menziesii, is thought to be restricted to the north-west of the South Island, and E. aucklandica is considered under most threat, inhabiting upper North Island with outlier populations in Lake Wairarapa near Wellington and Lake Hauroko in Fiordland.”

All three species are long-lived; with an estimated lifespan of 50 years or more.

“Size structure of E. aucklandica populations is skewed towards old individuals with little evidence of recruitment in northern streams. Like all unionids, E. aucklandica has a larval glochidial stage that parasitises fish (probably native diadromous fish) before transforming into juveniles that detach and sink into the benthos. Barriers to upstream passage contribute to the decline of native diadromous fish in NZ, which then negatively impacts mussel populations which need an annual influx of naïve fish hosts.”

Whole of catchment environmental management – upstream (water quality, sediment) and downstream (host fish passage) requirements – must be considered for conservation of kākahi.

“A recent conservation initiative is the translocation of 200 kākahi from lakes in the Wairarapa to Zealandia ecosanctuary’s upper dam in Wellington.”

Forest ringlet butterfly

“The forest ringlet butterfly was once widespread as far south as Greymouth and Lewis Pass in the South Island, but has become increasingly rare over the past 50 years. It is ranked as ‘At Risk–Relict’ in the NZTCS, but not listed on the IUCN Red-List.”

The cause of the decline in abundance and distribution is unknown.

“Habitat loss, over collection, parasitism, predation by introduced birds and rodents, as well as impacts of feral pigs on host plant abundance have all been suggested as contributing factors. In addition, introduced Vespula wasps may reduce forest ringlet populations. For example, once wasp populations on Te Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island began to decline in abundance, a resident population of butterflies was found for the first time.”

The causes of the decline (and the yet to be explained increase on Te Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island) need to be determined.

“Despite obvious risk of continuing decline in butterfly numbers, only surveys to monitor numbers have been undertaken to date. Possible interventions include captive rearing, further understanding of biology, standardising data collection on its distribution and population densities, and understanding of habitat requirements as ways to actively work to reverse the decline.

Hihi/stitchbird

Hihi are medium-sized (30–40 g) nectar-feeding forest-dwelling passerines. From the 1870s, hihi underwent a rapid decline in range and numbers; by the late 1880s they were restricted to a single remnant population on the 3083 ha isolated offshore island Te Hauturu-o-Toi/Little Barrier Island.”

Hihi build their nests in tree cavities, which makes them vulnerable to forest clearance and introduced mammal predators.

“Their decline in numbers coincided with extensive forest clearance and the arrival of ship rats and quickly turned to extinction on the mainland with the release of mustelids in the 1880s. Hihi are regarded as ‘Nationally Vulnerable’ in the NZTCS because existing populations are at least stable, but conservation dependent and are ranked as ‘Vulnerable’ in the IUCN red-list.”

“Beginning in the 1980s, an ongoing national recovery program aimed to increase the range and numbers of hihi using reintroduction. To date, there have been 21 translocations to eight different locations.”

Although mammalian predators had been eliminated on islands or heavily suppressed in sanctuaries where hihi were introduced, no population has become self-sustaining. All surviving populations outside of Te Hauturu-o-Toi are maintained by supplementary feeding, suggesting there’s not enough nectar available in young growth forests.

“Further, hihi are highly vulnerable to respiratory infections (aspergillosis) from the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus which is common in young growth forest habitats and spread through contaminated soil. Despite considerable effort by multi-agency hihi recovery groups since the mid-1990s, the species has little prospect of increasing in numbers until large tracts of mature forest are cleared of introduced predators on the mainland and suitable regenerating forests mature on offshore islands.”

Grand and Otago skinks

“Grand and Otago skinks, collectively known as GAOS, inhabit middle-altitude fractured schist in shrub and tussock grasslands of Central Otago in the South Island. Their ranges are <10% of historic estimates, and both species now occur within two widely spaced and genetically diverse groups in the east and west; the genetic diversity is such that the eastern and western populations are managed as separate units.”

The NZTCS ranking for both GAOS improved from ‘Nationally Critical’ to ‘Nationally Endangered’ in 2015, with O. otagense ranked as ‘Endangered’, and O. grande as ‘Vulnerable’, in the IUCN Red-list (IUCN 2017).

“Persistence of the western populations is uncertain, and all remaining populations are dependent on ongoing conservation action. GAOS are at risk from a combination of habitat destruction, predation/competition with invasive species and wildlife trafficking.”

Both skink species are large-bodied with late sexual maturity and low reproductive output, but unlike other large lizard species in New Zealand, they don’t have any mammal-free island strongholds.

“To date, most research and conservation knowledge is based on the eastern populations, which are also easier to keep successfully in captivity than individuals from western populations. Sustainable harvest of western juveniles for genetic security was done (2009–2013), and long-term monitoring of remaining natural populations indicated a probable steady decline susceptible to stochastic events.”

In 2014, an emergency salvage of 85 GAOS from all known western populations was carried out.

“Forty-five juveniles (a mix of wild and captive-raised) were immediately released to a community-led 0.3 ha fenced sanctuary, but most vanished. The captured adults were paired for captive breeding, with a 5-year plan to release to a new 14-ha predator-exclusion area (completed 2015); unfortunately, survival and breeding success were low in both the translocated population (juveniles) and captivity (adults). In December 2018, 67 of the surviving captive-held GOAS were released early from captivity into the 14-ha sanctuary.”

“In the next 30 years, wild GAOS in the western and non-protected eastern areas seem on a trajectory for extinction. With ongoing predator control and habitat protection, eastern managed populations could persist at present levels. Coupled with the new predator-free sanctuaries developed by community-led projects and extensive control of predators in other areas, survival of western GAOS may be improved in the future.”

Overall, the 7 case studies reveal a variety of threats that originate from the effects of agriculture and harvesting, irreversible habitat modification and loss, impediments to connectivity, disruption of parasite–host relationships, introduced species and susceptibility to disease, and are further exacerbated by political and legal inertia, low prioritisation and limited conservation funding.

“Removing predatory mammals as the sole management approach will not be enough for intractable species, which are impacted by a suite of complex and interacting threats and stressors. Instead, restoration of entire ecosystems or landscapes may be the only viable solution to these complex problems. Major problems remain to be resolved for numerous species, and these require mobilisation of the scientific community, ongoing engagement with the New Zealand public and strong leadership. A growing commitment from people, including increased funding, can give the people of New Zealand some hope for the future of the intractable species.”

The full article is published in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. Only the abstract is freely available online to non-subscribers.

Intractable: species in New Zealand that continue to decline despite conservation efforts (2019)