Graeme Elliott has been studying our native birds for 45 years and using his knowledge we’ve put together an overview of how we can best protect our native birds in a mast year.

The right tool for the job

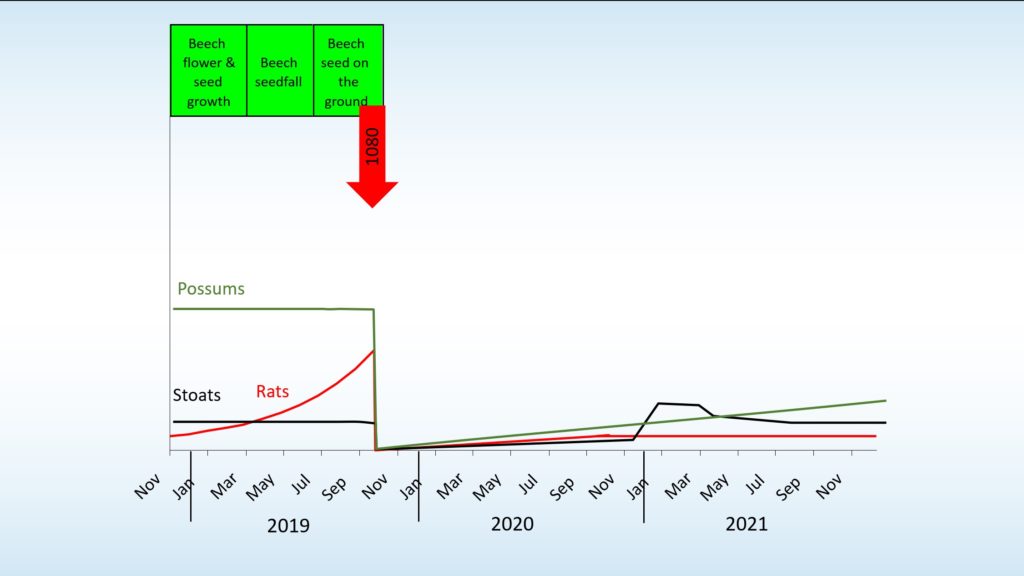

For him the message is clear, the main tool that can be used to reduce the impact of a mast year on our native species is 1080. Strategic operations at the right time, in the right place can and do make a huge difference.

If a 1080 operation is done at the right time (ie as the rat and mouse population is beginning to skyrocket) then rat and stoat populations can be prevented from booming. This can have a huge effect on the nesting success of our native species. It also has a long term effect on the predator populations giving our native species a reprieve from predation.

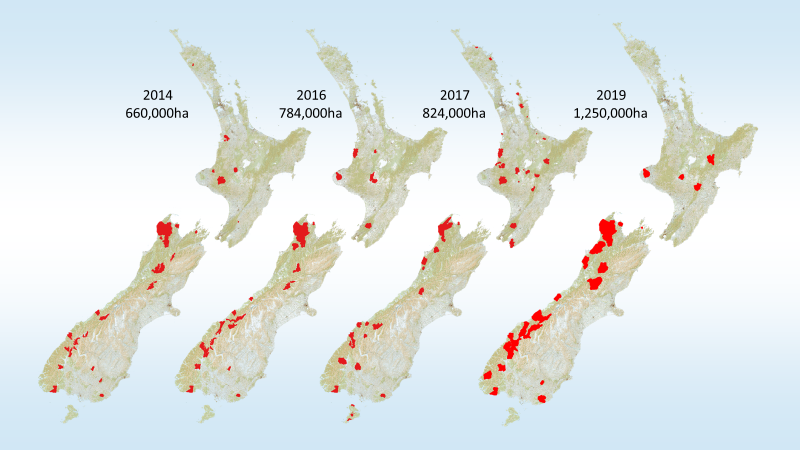

Below are the sites where DOC has undertaken 1080 control in the past three years. Planned control for 2019 is also shown.

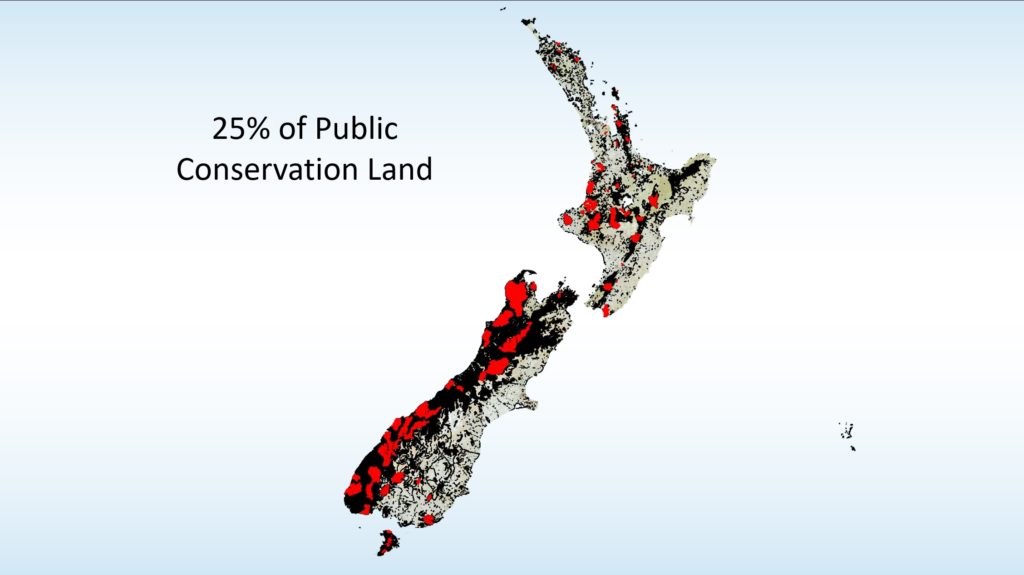

It’s only a small portion of the country. Combined with trap-lines it is only 25% of the conservation estate, or 33% of the forest on Public Conservation Land. We need to do more to cover a wider range of landscapes and enable more of our native species to thrive.

What is the impact?

Rat tracking is done before and after an operation to monitor success. In 2014, the last significant mast event, 21 out of 25 operations got rats down to below 10% rat tracking. 84% of operations were very successful. Even operations that were less successful removed 80% of the rats. Essentially, a disaster was averted with our native species.

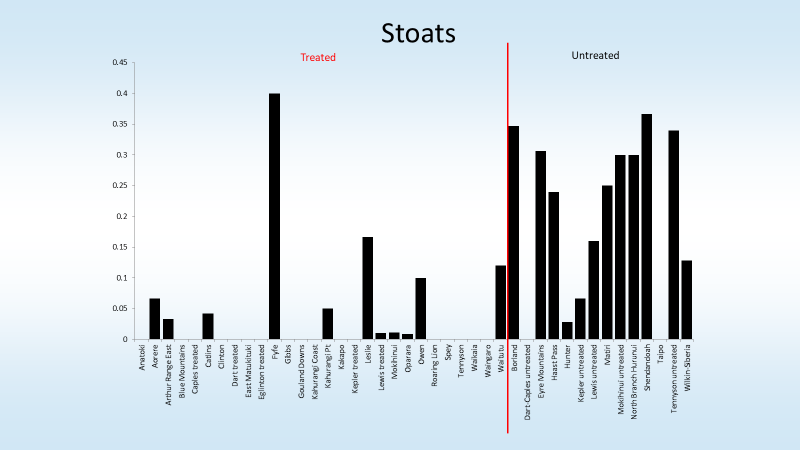

Stoats are usually only monitored once a year so there aren’t results before and after a drop. However, sites can be compared with and without 1080 treatment to see the difference.

The average tracking rate for stoats at untreated sites is 20%. Sites treated with 1080 have a tracking rate of 3%. Most of the sites where the stoat numbers were not significantly impacted also had high rat tracking rates i.e hadn’t managed to significantly reduce rat numbers.

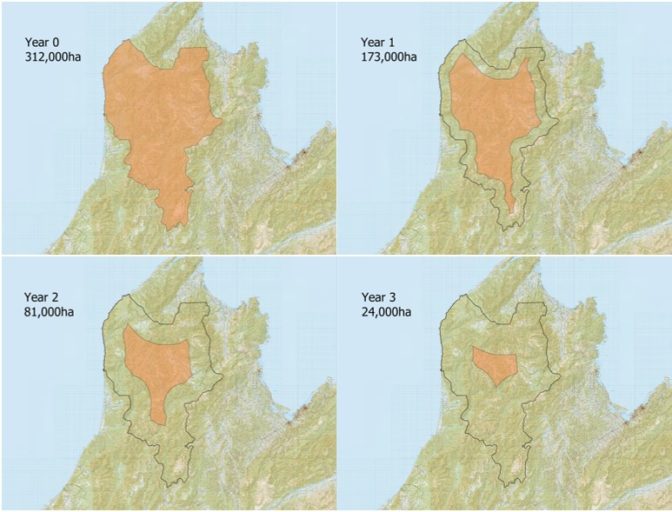

The good news is that once stoats are removed from a large area they take a long time to repopulate that area. They gradually repopulate from the edges of the controlled area. This means the species in the middle of the treatment area can have several breeding seasons without impact from stoat predation.

So if larger treatment areas can be controlled then the habitat in the middle can be protected from stoats for a reasonably long period.

So why can’t we use traps?

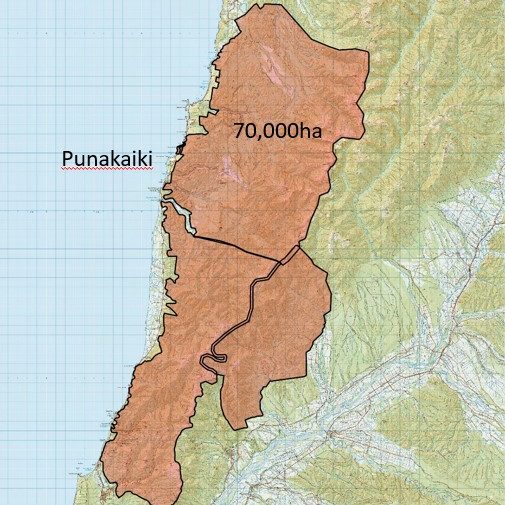

It comes down to maths! An area of 70,000 hectares can be treated in three days with helicopters accurately applying 1080.

To trap the same area for stoats (using DOC best practice of 1 trap per 10 ha) would require 7,000 traps, 2,000 km of tracks and 200 person days per check (of which best practice stipulates you do each month).

But to trap for rats a much denser trap network is required, a trap at each of the dots outlined below. This would require 70,000 traps, 7,000 km of tracks and 700 person days per trap check.

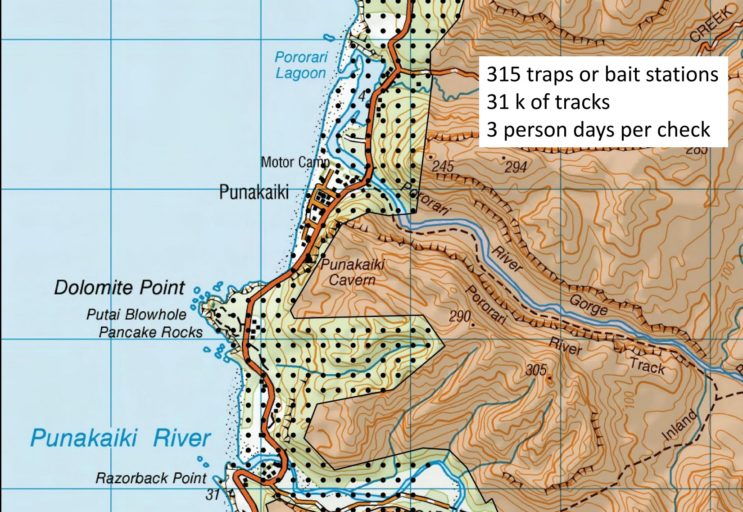

One of the best things community groups and individuals can do to protect our native species is to use traps to support the landscape scale control and trap around the edges of the treatment area.

Trapping the edge of this treatment area requires 315 traps, 31 km of tracks and only takes 3 days per trap check. This provides a line of defense and slows the re-invasion of predators back into the treatment area and ensures the benefits last longer.

So how does 1080 affect our native species?

It is common knowledge that our native species are vulnerable to predation by rats and stoats. 1080 significantly reduces rat and stoat populations and enables native species to breed. However, what about the native species that may eat 1080 bait? Over the years the Department of Conservation and others have undertaken a lot of research on the impact of 1080 on various native species. 1080 does kill some birds – weka and kea are particularly vulnerable. However studies show that the overall population still benefits from the predator control.

With thanks to Graeme Elliott from the Department of Conservation (DOC) for sharing his knowledge and images. Find out more about DOC’s predator control programme at Tiakina Ngā Manu.