Between 2010 and 2016, the community group Friends of Flora Inc., in partnership with the Department of Conservation, translocated 44 roroa (great spotted kiwi, Apteryx haastii) to the Flora Stream area in Kahurangi National Park. But that was just the beginning of the project. Each kiwi was fitted with a VHF transmitter and, for the next 2-8 years, volunteers monitored their locations by radio-telemetry.

Robin and Sandy Toy, from Friends of Flora, report on the project and what they learnt from the long-term post-translocation monitoring in an article recently published in Notornis, the journal of the Ornithological Society of New Zealand.

“Effective post-release monitoring is necessary to determine both short- and long-term success of translocations and reasons for failure. Roroa pose particular challenges for intensive monitoring; they are nocturnal, sensitive to disturbance, and live at low density in mainly remote, mountainous terrain.”

Good predator control was a key requirement for the project. Kiwi of all ages are vulnerable to predation by ferrets and dogs and young kiwi and kiwi eggs are vulnerable to predation by other mustelids. Mustelids and dogs were thought to be responsible for the previous disappearance of roroa from the area.

“There are anecdotal reports of kiwi from the project area dating back to the 1970s and 1980s. Roroa are found in the adjacent Cobb Valley albeit with low call rates. However, in a 2011 survey of the area between the Flora and the Cobb, no kiwi were detected in 1,579 hours of acoustic recording. It was assumed that predation by dogs and stoats caused the loss of roroa from the project area and that habitat conditions are otherwise suitable for roroa.”

In partnership with DOC, Friends of Flora hoped to achieve a sustainable population of roroa.

“The project area was chosen because it has more intensive predator control than much of the roroa range, it was recently occupied by roroa, and it has comparatively easy access, enabling monitoring and public engagement. Between 2010 and 2016, four wild-to-wild translocations of adult and subadult kiwi were performed. Forty-four kiwi were translocated, meeting the recommendation of more than 40 founders when establishing a new kiwi population.”

Post-translocation fieldwork was performed by Friends of Flora volunteers working with two part-time, contracted ecologists accredited to handle kiwi. Monitoring the kiwi involved covering a large area of sometimes rugged terrain.

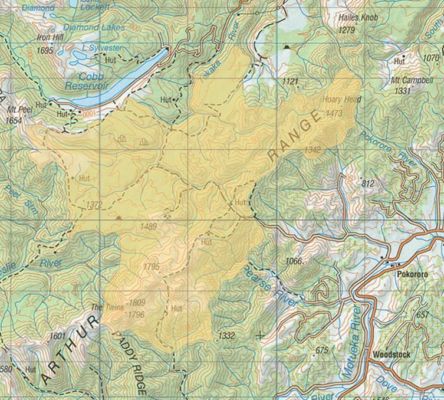

“The Flora Stream lies to the north of Tu Ao Wharepapa (Mt Arthur) in the Upper Takaka River catchment. The project area covers approximately 10,000 ha ranging from 700 to 1,500 m altitude. Rainfall for the Mt Arthur Ecological District is between 1,500 and 4,000 mm/annum, wetter towards the west. Silver beech is the predominant canopy species with red beech at lower altitudes and mountain beech at higher altitudes.

The area was made part of Kahurangi National Park in 1996. Stoat trapping was started in 2001 and, by 2020, the network of traps had been expanded to cover about 9,000 hectares.

“Traplines are spaced approximately 1 km apart with double set DOC 150 traps at 100 m intervals along the lines. Traps are serviced approximately monthly. The area adjoins the Cobb Valley in which the community group Friends of Cobb have trapped stoats since 2006. The project area is on the edge of a much larger block that has received four aerial applications of sodium fluoroacetate (1080) for control of rats or brushtail possum. Secondary poisoning of mustelids occurs from such applications. The threat from dogs has declined since a permit is required to bring a dog into a National Park.”

With predator control well underway, translocation of kiwi could now be considered.

“Forty-one adult and three sub-adult kiwi were translocated into the Flora from four separate source sites in NW Nelson. Multiple translocations were performed for logistical reasons, to reduce the impact on source site kiwi populations, and to maximise genetic diversity of the new population. We attempted to translocate established pairs of roroa.”

Each translocated kiwi was fitted with a unique alpha-numeric metal band and a leg-mounted VHF transmitter.

“In each translocation all kiwi were released in the same general area. In the first two translocations, known partners were released into burrows within a few metres of each other. On four occasions in subsequent translocations, partners of known pairs were released in the same burrow. Four kiwi that dispersed outside the trapped area were retrieved and released a second time within the area.”

The monitoring team aimed to locate all translocated kiwi the day after release, then twice a week for two months and thereafter at about fortnightly intervals.

“Monitoring continued until May 2018 when achievement of operational targets relating to dispersal, pair formation, and location of home ranges within the project area had been demonstrated. Transmitters were then removed.”

Most monitoring estimated the position of daytime roosts, but some night-time radio-telemetry was also carried out.

“At night, kiwi may move to areas in which they do not roost. We monitored kiwi night movements on 13 occasions spread over five years, with teams taking bearings of any kiwi within range every 20 minutes throughout the night. Bearings were taken from two to four fixed locations; observers did not move location during the night. Bearings taken at night are approximate as the signal volume fluctuates as the kiwi moves.”

Measurements were used to calculate a dispersal range for each kiwi for the period from release until it settled into a home range or until monitoring ended if earlier.

“A kiwi was identified as settling in a home range if it paired and remained in an area for more than six months or, for a single kiwi, if it remained in an area for more than a year. Single kiwi were identified post-hoc as taking longer to settle than kiwi in pairs, hence the difference in definition.”

Monitoring of 28 roroa continued until they established a home range, but the monitoring of the other 16 was truncated.

“The dispersal phase was very variable; kiwi that established a home range dispersed for between 9 and 878 days before settling and covered between 33 and 1,745 hectares. The maximum straight-line distance an individual kiwi moved from its release site was 9.8 km but its dispersal route will have been longer. Dispersal of some kiwi appeared unidirectional but others moved back and forth. Six kiwi paused in an area for up to 11 months before moving.”

Established kiwi pairs settled more quickly.

“Dispersal of kiwi in established pairs that stayed together through the translocation was of significantly shorter duration and covered a significantly smaller area than the dispersal of kiwi that formed new pairs in the project area. However, only three of 11 translocated pairs that were monitored until they established a home range stayed together. Of the four pairs in which the partners were released in the same burrow only one pair stayed together.”

Forming pairs and establishing territories had something of a soap-opera complexity.

“Pairs were assumed to have formed when male and female kiwi overlapped their home range or bred. Nine kiwi formed transitory associations during the dispersal phase, including two comprised of same sex birds. By the end of radio-telemetry monitoring, 34 of the translocated kiwi had paired, four had not and monitoring of six was truncated too soon to tell. Four kiwi are known to have paired with non-translocated kiwi, one with an immigrant, most likely from the Cobb Valley, and three with offspring of translocated birds. Seven of the pairs comprised partners from different source sites. Five kiwi changed partners during the project, three of them after they had bred. The members of one of the pairs that separated after release occupied adjacent home ranges with new partners.”

“By the end of the radio-telemetry monitoring, mapped home ranges were spread over approximately 5,000 ha. Last known locations of kiwi whose monitoring was truncated were dispersed over 10,000 ha. All but one of the home ranges were within 1 km of another pair. There was one instance of two single females sharing a home range, although they were never found in a burrow together.”

Night monitoring showed that kiwi moved beyond their home range, but not far.

“All night monitoring was carried out over five years on 13 occasions during December to May. Periods of non-breeding, incubation and up to two months after chick hatch were covered. Sixteen kiwi were monitored, up to six on any one night, giving a total of 69 nights of kiwi activity. On 24 occasions a kiwi moved outside the annual home range estimated from daytime roosts, usually into space between adjoining pairs’ annual home ranges. The maximum distance outside the home range was about 600 m, the average foray length was 200 m. Seven incursions into another pair’s home range were observed, all less than 100 m.”

Monitoring kiwi for eight years meant that when the birds dispersed further than expected, trapping could be extended to keep them protected from predators.

“Monitoring showed kiwi were establishing home ranges outside the trapped area. Trapping was extended to cover an additional 4,000 ha in the Deep Creek, Ghost Creek and Grecian River areas to encompass this dispersal. Frequent monitoring also enabled retrieval of four roroa that dispersed further away where they were vulnerable to predation. All paired within the project area after their second release. Six kiwi that dispersed outside the project area and could not be retrieved likely remain part of the functional translocated population as they moved to adjacent areas.”

After eight years, 30 kiwi (68%) were known still to be in the project area, six had dispersed outside it, five had disappeared with their last tracked location being within the project area, and three had died. One of the kiwi that died did so three years after translocation due to emaciation consistent with starvation and/or old age; the other two died during dispersal, one in a tomo (sinkhole) and one stuck in a burrow. Twenty-eight (93%) of the kiwi remaining in the project area were known to have a partner, at least two of the pairs involved kiwi hatched in the Flora.”

The extensive monitoring meant that several translocation lessons were learned.

“This study showed that roroa can settle in a stable home range after nine days, but they can also take nearly 2.5 years. Annual home ranges shifted and, as a result, multi-year home range expansion for some kiwi continued for six years which may result from translocation but could be normal for a relatively low-density population.”

“Retrieval of kiwi or expansion of a predator control area may be of great benefit during the dispersal phase but are unlikely to be justified by subsequent home range expansion. Therefore, we conclude that, in relation to dispersal, radio-telemetry monitoring should continue until stable home ranges are demonstrated to have established, which in the Flora Stream area took more than 2.5 years. To maximize the effectiveness of the translocation, all kiwi should be monitored since dispersal is very variable between individuals.”

In each translocation, kiwi were released in clusters in areas without resident kiwi.

“Some kiwi dispersed several kilometres before establishing a home range, but of 17 pairs that established home ranges, all except one settled within 1 km of at least one other pair. Roroa calls of both sexes are audible from more than 1 km away in good conditions. This suggests there was acoustic anchoring.”

Home ranges established over a larger area than was predicted prior to the translocations.

“Currently, the trapped area is about 9,000 ha, similar to the 10,000 ha minimum area required for long-term kiwi persistence, but much of the trapped area is unoccupied. Understanding habitat and range requirements is a complex issue but is clearly fundamental to translocation success. In the project area, several kiwi from later translocations established home ranges in areas through which kiwi in earlier translocations had dispersed, suggesting the habitat was suitable for roroa, but unknown factors discouraged the previously released kiwi from settling there.”

One further ‘lesson’ was demonstrated by this project – confirmation of the valuable contributions that can be made by volunteers.

“Post release monitoring is often viewed as difficult and expensive, and even optional. The ability of community groups to deliver such an effort has been questioned. The project has shown that with training, support and leadership, volunteers can provide the long-term commitment and carry out the tasks necessary for long-term post-translocation monitoring at manageable cost.”

More about Friends of Flora