The government plans to reform the country’s strict regulations on genetically engineered or modified organisms outside the lab. What does this mean for the predator free movement? We asked experts in the predator free sector to comment.

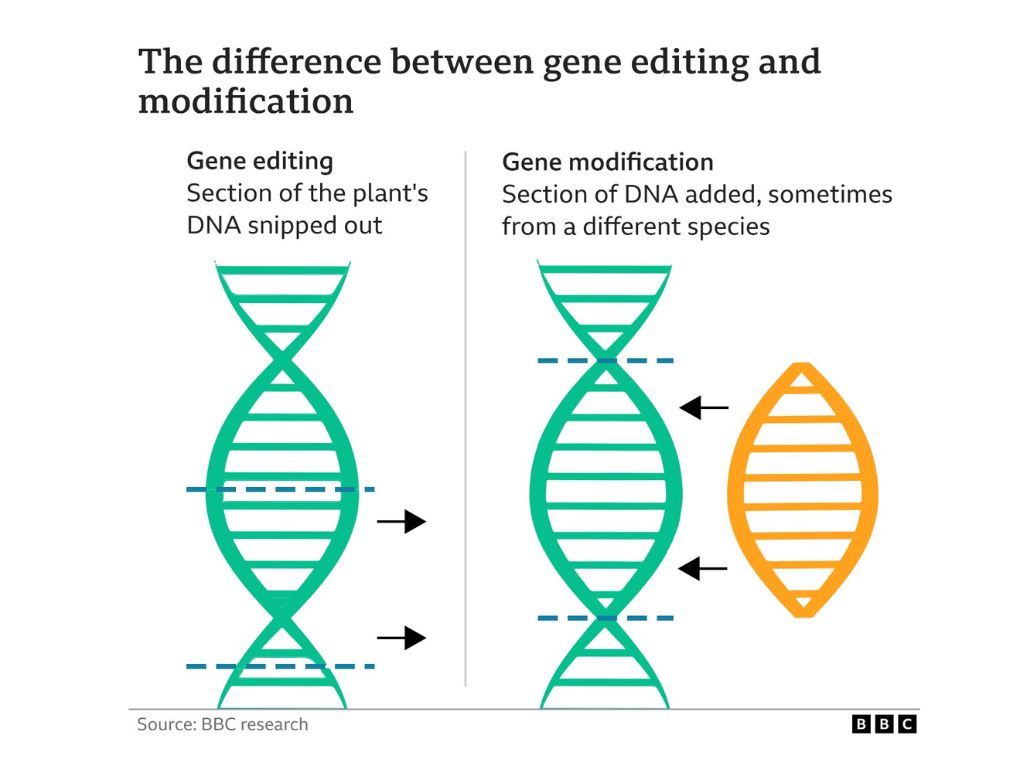

Gene editing for conservation is a technique used to change the DNA of animals to help manage or reduce harmful species.

In most scenarios, the target for gene editing is an animal’s fertility or sex ratio.

For nearly three decades, New Zealand has had strict regulations on genetic technology, more or less confining research inside laboratories.

The current government has introduced the Gene Technology Bill 2024 to “enable the safe use of gene technology and regulated organisms”. Public submissions on the bill are open until Monday, 17 February.

Phil Bell, innovation director, Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP)

“There’s no denying that gene technology has massive potential for predator removal. However, applying it in practice will require significant investment and a lot of time. As much as we understand of it (and we’re by no means experts), gene technology will not be the silver bullet for predator elimination – but it could be a hugely effective addition to the toolkit that gets us to a Predator Free Aotearoa.

Early signs indicate that it could help to tackle rats (rapid breeders with multiple generations in quick succession), but less so possums or stoats. It may be that this is a tool better suited to improve the overall ecosystem outcomes for Aotearoa; for example, perhaps it’ll find its niche as a tool to manage mice long-term.

Regardless, for this opportunity to be even close to becoming a reality, we – as a community, as a society, as a nation – need to start having the conversations that will determine how this tool might be used in Aotearoa as soon as possible. It’s a big concept to grapple with, and new ground for us all. Working through that together will take time, which is the nature of new tools.

While we’re on the journey there, we need to maintain our focus on predator elimination work. The risk of biodiversity loss and declining ecosystem resilience is a challenge we need to address now.”

Dr Andrew Veale, wildlife ecologist, Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research

“The government’s proposal to modernise genetic engineering laws is clearly an important move for the agricultural, horticultural, aquaculture, and biotech sectors.

For conservation, I think not much will change on the ground in the short to medium term, but this change will allow the conversation to move forward. To my knowledge there isn’t a GE technology that already exists overseas that we have been prevented from using for conservation by the previous ban on GE.

It is not a situation where we can now say: “At last I will be able to fix this conservation problem with this change in legislation enabling me to use X”. Reversing the ban does change what level of collaboration we can be involved with internationally, and it can change the mindset of where we might go next.

We need to discuss the potential of genetic engineering in conservation across society, and now, without an outright ban, these conversations should advance.

There are various avenues that GE technology could be used in conservation, but all of these will have long development periods, and consultation processes. Vaccines for wildlife diseases could be developed and spread. Fertility control through immunocontraception of pests may be able to be developed. Possibly, even targeted diseases that are highly specific to species could be developed.

The one that everyone talks about is gene-drive technology, which may be able to be used to alter the sex ratio of a pest population to drive it towards extinction. Gene-drives capable of this have not been developed yet for mammals, and this area remains ‘possible future technology’ rather than a reality, and considerable amounts of research is being done internationally. Maybe one day it will become a real prospect for the humane suppression or eradication of pest animals, and we can now play a greater part in this international research and conversation. For species with long generation times, like stoats and possums, gene-drives are unlikely to produce meaningful results, but for rodents, if they are developed and work well, this could be a game-changing technology.

For conservation, the funding (particularly for large, or blue-sky projects) always comes ultimately from the government, filtered through some ministry or government-controlled entity. Genetic research is technical, expensive, long-term, and the outcomes of this sort of research are uncertain. That means that in terms of conservation and GE, lifting a ban will only have an effect if funding is created to expand our capacity and develop the technology. The statement “you are no longer banned from driving the car” only makes sense if the car exists, functions, and has fuel. If the government is interested in progressing genetic technology for conservation, they will have to not only allow it, but also support it with investment.”

“If the government is interested in progressing genetic technology for conservation, they will have to not only allow it, but also support it with investment.”

– Dr. Andrew Veale

Anna Clark, PhD candidate, Department of Anatomy, University of Otago

“This long overdue change represents an important step forward for the predator free movement, since Aotearoa NZ must see significant improvements in pest control efficacy to achieve successful eradications on the mainland.

Species like ship rats and house mice have high reproductive capacities, making them excellent candidates for genetic fertility-based control technology, for example, gene drives, which affect only the target species since transmission is from parent to offspring.

The new legislation is an opportunity for local researchers to be more active contributors to the development of genetic control technology, and to produce systems that are tailored to our local context.

The new legislation is an opportunity for local researchers to be more active contributors to the development of genetic control technology, and to produce systems that are tailored to our local context. Developing these fertility-based gene drives in mice (mammalian model species) has been difficult, so we need a larger collective effort to do the due diligence required to produce functional versions of the technology that we could potentially use. This is an expensive proposition, so consistent progress will require the allocation of dedicated funding to support building local capability and capacity, while further strengthening international collaborations.”

Conflicts of interest: Anna has received a PF2050 Ltd Capability Development Grant to explore gene drives in complex ecosystem models.

Dan Tompkins, science director, Predator Free 2050 Ltd

“Overhauling the regulation of gene editing and other genetic technologies may have consequences for predator free in the mid to longer term.

For the short term, research into such is already underway in contained laboratory settings in New Zealand under current regulations.

Unlike similar work overseas on pest insects such as mosquitoes, which is looking to move into field trials, we still have several years of work in containment to go before reaching such stages (should the research be successful) for application to mammal pests.

At that stage, if there is the social, cultural and political appetite to see if we can apply such technologies for predator free – and there is a need they could address that other tools can’t – that is when steps to provide a regulatory process that better balances their potential risks and benefits could help.

This could help faster realise those benefits for achieving predator free.”

Marcus-Rongowhitiao Shadbolt, Melanie Mark-Shadbolt, and Simon Lambert, Te Tira Whakamātaki

“We recently undertook research (PDF, 4.3 MB), alongside social scientists from Auckland and Otago Universities, to understand public perceptions of genetic technologies for environmental purposes.

For Māori, there was a lot of discomfort with unknowns associated with synthetic biology, especially on the wide-ranging implications to the whakapapa of species.

There were only limited cases of cautious openness to some scenarios (which often featured pests such as possums as opposed to native species), and significant concerns remained about the unknown consequences of synthetic biology – including the ecological impacts, ethical implications, and impact on the food chain.

Many of the Māori participants advocated for strong regulation through tikanga (cultural processes) and through consistent and genuine government engagement (mediated by trust of that government).

For any synthetic biology in the PF2050 movement to be used, this research showed a necessity for a concerted effort to educate Aotearoa openly and effectively on these tools. It will equally rely on Te Tiriti-based engagement with communities on the technologies and their proposed use, including the development of culturally sensitive and inclusive decision-making processes that uncompromisingly incorporate the varied views and values of iwi and hapū.

For more information, visit Te Tira Whakamātaki’s reports and educational resources web pages.”