In many wildlife sanctuaries around New Zealand fences make it almost impossible for most introduced predators to get in. But mice can still sneak through – and without those larger predators, their populations can explode.

But is this fact something we should be worried about? A five-year research project led by Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research says there is some cause for alarm. Invertebrates are a large part of a mouse’s diet, and the study revealed an increase in mice is bad news for native species such as caterpillars and wētā. Leading to a chain reaction that also spells bad news for the birds that rely on them for food.

Monitoring mice in a predator free sanctuary

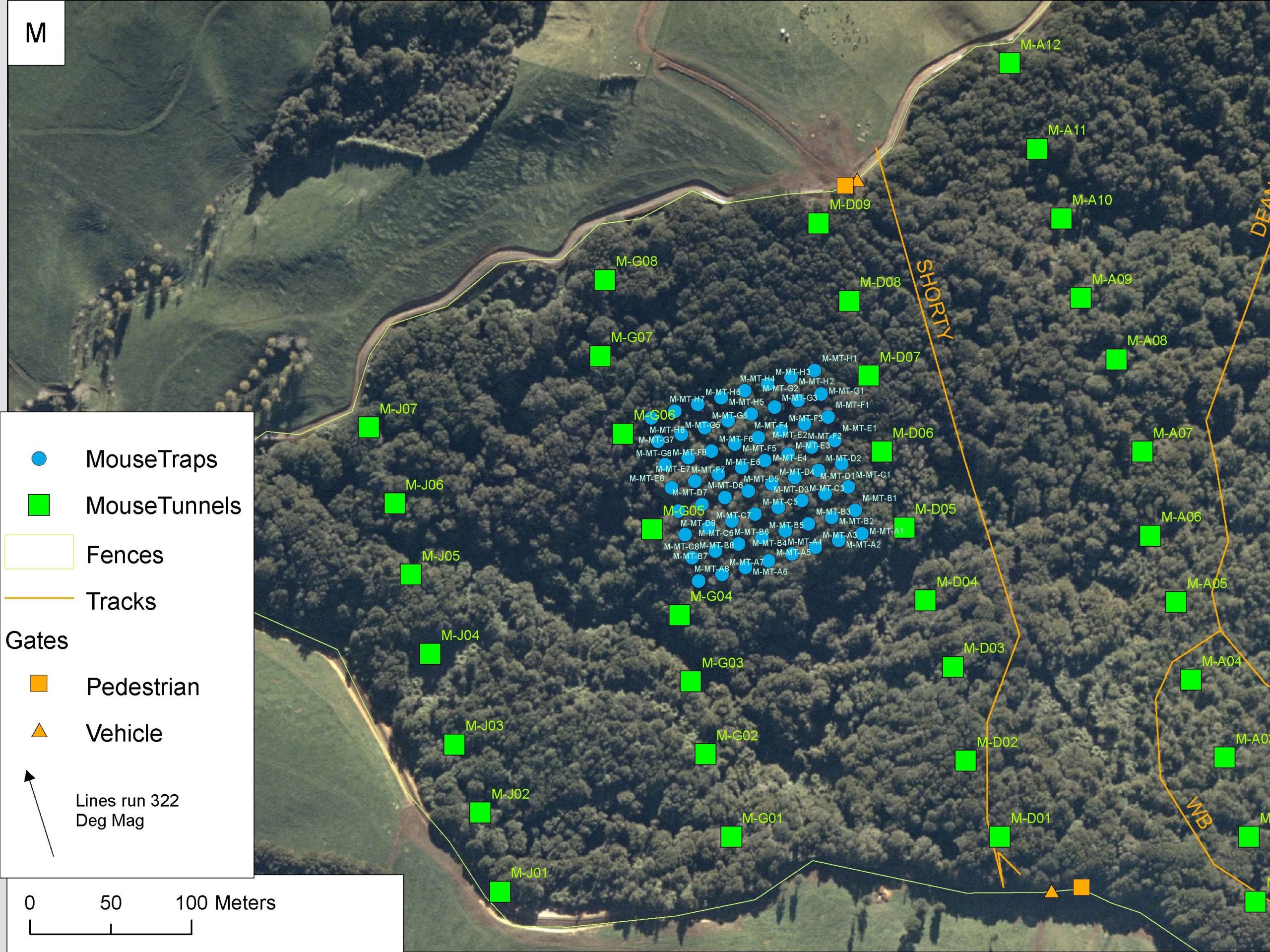

Waikato is home to one of the longest predator-proof fences in the world. Stretching for 47km, the fence protects the 3,400 hectare Sanctuary Mountain Maungatautari. It was the perfect location for researchers from Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research to run their five-year project to find out what impact mice have on invertebrates.

By controlling the numbers of mice in separately fenced areas, researchers could count invertebrates in both a high-density mouse area and a low-density mouse area. Halfway through the project they reversed what they were doing to swap the densities.

Now they’ve published their research in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology. We spoke to co-author John Innes, Senior Researcher in Wildlife Ecology, to find out more about the study and its implications.

Complex community

You might not notice them at first when you visit a wildlife sanctuary, but all around you are hundreds of species including beetles, spiders, grasshoppers and earthworms. They live together in a very complex community. Yet to date, John says there hasn’t been a lot of research on invertebrates in sanctuaries.

“Invertebrates are difficult to monitor. Climate from year to year has a really big influence on them so you’ve got to monitor them over quite a long period to understand how their populations work.”

Using different methods to target different species, the researchers surveyed invertebrates in both areas. They identified wētā footprints in the tracking tunnels, caught beetles in pitfall traps, and sifted through leaf-litter.

At the end of the study, they found strong evidence that mice limit invertebrate populations, and that too many mice affect the number of different invertebrate species you can find.

Ecological integrity: replacing predators – not getting rid of them

What did Aotearoa New Zealand’s invertebrate community look like pre-human settlement?

According to John, we don’t actually know. The aim of restoration is to restore ecological interactions to what they were like before humans – this doesn’t necessarily mean an increase in population for every species.

In fact, if we were to remove mice from New Zealand, it’s likely invertebrate numbers would stay exactly the same. How is this possible?

If you remove mice, then you’re providing a huge amount of extra food to native animals. A wētā that isn’t eaten by a mouse, might be eaten by a weka.

John says it can be difficult for people to wrap their heads around this concept.

“It’s a real lesson to people that we’re not trying to stop predation. No-one is trying to stop competition – we’re restoring original limiting factors. We’re looking to replace introduced eaters of invertebrates with native eaters of invertebrates. And whatever the new community makeup for these invertebrates looks like is presumably more correct than what it was before.”

It’s important to realise that the wildlife we observe now at Maungatautari has already survived seven centuries of kiore and other introduced predators, says John.

“What we have left is pretty resilient. Yet, obviously, there is still quite a lot of bounce back if you take mice away.”

While the study didn’t look at lizards, John believes that an increase in mice could be the final straw for their survival. Lizards can escape from rats by hiding in tiny crevices, but mice can squeeze through and find them.

Looking forward

While removing larger introduced predators from sanctuaries boosts overall biodiversity, letting mice stay can be catastrophic for invertebrates and lizards. And mice can cause other problems. They can interfere with monitoring and control of other species, undermine fences, or even attract larger introduced predators into the sanctuaries.

As John says, “Mice are hard.” Learning how mice populations can skyrocket in sanctuaries has wider implications for introduced-predator control throughout Aotearoa New Zealand.”

There’s hope for the future – the researchers expect that methods for controlling mice will improve, so that one day places such as Maungatautari can be mouse-free.

In the meantime, you can help restore ecological integrity in your own garden, with some backyard trapping.