Rat-trapping started early in Aotearoa’s history. The Polynesian ancestors of Māori brought the kiore across the Pacific in their voyaging waka, probably around the 13th Century AD and early Māori developed several types of ingenious rat traps to catch them.

Aotea, Horouta and Māmari waka traditions mention that kiore were passengers on their voyages to Aotearoa. Carvings on a window frame of Te Ōhākī wharenui at Roma marae in Ahipara depict the story of Ruanui’s kiore. Ruanui was captain of the Māmari canoe. On arriving in Hokianga Harbour, he released his kiore onto an island now called Motukiore (rat island).

‘Kiore’ appear in other names too – in the names of people, houses, landscapes, plants and animals. Nihootekiore (rat’s tooth) is a place, Hine-kiore (rat girl) is a name, and tūtae-kiore (rat excrement) is a plant. Kiore is the name of a star cluster, while kiri-kiore (rat skin) and Pū-kiore (rat’s nest) are patterns in carvings and tattoos.

But back to those traps. Kiore soon spread across the land. They’re omnivores and food was in plentiful supply. They eat seeds, fruit, leaves, bark, insects, earthworms, spiders, lizards, and bird eggs and hatchlings. Kiore often take pieces of food back to a ‘husking station – a safe place to properly shell a seed for example. This not only protects them from predators while they’re eating, but also from rain and other rats. Husking stations are often found among trees, near the roots, in fissures of the trunk, under rock piles and under fronds shed by nikau palms.

But back to those traps. Kiore soon spread across the land. They’re omnivores and food was in plentiful supply. They eat seeds, fruit, leaves, bark, insects, earthworms, spiders, lizards, and bird eggs and hatchlings. Kiore often take pieces of food back to a ‘husking station – a safe place to properly shell a seed for example. This not only protects them from predators while they’re eating, but also from rain and other rats. Husking stations are often found among trees, near the roots, in fissures of the trunk, under rock piles and under fronds shed by nikau palms.

Kiore were eaten by early Māori, who treasured them as an energy-giving food source and a delicacy. They were either skinned and roasted over a fire, or more elaborately baked while bound in a clay ball among the ashes, raked out and cracked open. The skin and fur remained stuck in the clay while the edible pieces were easily removed and eaten, save a couple of large bones and the tail. Alternatively, kiore would be preserved in their own fat and stored in calabash gourds, reserved for guests of Rangatira at special feasts.

At least 3 different traps for catching kiore are known.

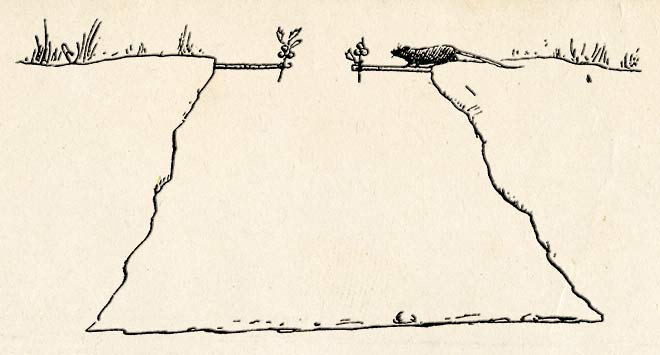

With a pit trap, known as a rua torea, the kiore walked across the stick to the bait and slipped into the pit, which had been dug one and a half metres deep. There they were collected by a trapper. Other traps used a spring snare mechanism. One snare trap was known as the taupopoki. With this trap, the kiore would go part way through a loop to reach the bait. The rat would pull at the bait, releasing the stick that stopped the loop from springing up.

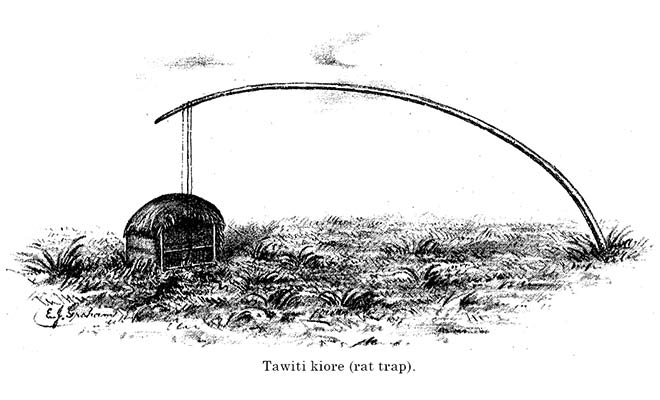

Thirdly there was a portable trap known as the tāwhiti makamaka, made of mānuka bark, aka pirita (supplejack) and muka (flax fibre). A kiore would be lured into the trap by the scent of berries and would then chew through the cord to reach the bait. When the cord snapped, the bent stick would spring up and trap the rat in a loop inside the trap.

Kiore were known to roam well-trodden paths at dusk and through the night and these tracks were valued by early hunters, staked out with rat traps according to whanau or hapu territory.

As well as being stored for food themselves, kiore were a pest and raider of Māori food stores and so influenced storehouse design. Pātaka were raised off the ground to prevent kiore getting into the food and, although parts of the pātaka were carved, the posts generally had no decoration – so as not to provide footholds for climbing rats.

Although kiore were regarded by Māori as relatively clean animals which lived mainly on insects, fruits, eggs and chicks, Māori were less impressed by the ship rat and Norway rat which arrived with European explorers, sealers, whalers and settlers. In an early scientific report Maori were said to have described European rats as “detestable creatures, mischievous thieves, house-gnawers, garment-destroyers, with an abominable habit of defecating on articles of food, absolutely disgusting creatures”

Not far wrong there.

Thus many Māori still value kiore – but not other rats – even today, in spite of their role in the extinction of a number of other endemic species. The Ngātiwai tribe, for example, consider themselves guardians of the kiore. They believe there are cultural and historical reasons that the rats should survive.

Introduced ship rats and Norway rats have taken over from kiore on most of the mainland since the 1890s, but a few kiore populations are left, scattered in remote areas or on islands. Two islands in the Hen and Chickens group, Mauitaha and Araara, have now been set aside as sanctuaries for kiore.

Elsewhere in the world, the Polynesian rat is widespread throughout the Pacific and Southeast Asia. Interestingly, mitochondrial DNA analysis suggests that the kiore (Rattus exulans) originated on the island of Flores.

The IUCN Red List considers Rattus exulans native to Bangladesh, all of mainland Southeast Asia, and Indonesia, but introduced to all of its Pacific range (including the island of New Guinea), the Philippines, Brunei, and Singapore, and of uncertain origin in Taiwan. Because it can’t swim over long distances, it is considered to be a significant marker of the human migrations across the Pacific, as the Polynesians accidentally or deliberately introduced it to the islands they settled.

Kiore feature in proverbs, songs and dance. ‘Ko tini o para kiore’ (a swarm of rats) refers to a heavily populated area. ‘Honoa te hono a te kiore’ (gather as rats do) was used by the Ngāi Tūhoe ancestor Karetehe to rally warriors who were facing defeat. His warriors knew to group together like rats and run straight through enemy ranks.

Although appreciated as an energy-giving food, kiore were used as a metaphor for weakness. A weak person was said to have ‘he uaua kiore’ (sinews of a rat), compared with a strong person’s ‘he uaua parāoa’ (sinews of a whale). A person whose boasts exceeded his abilities might hear the saying, ‘He nanakia aha tō te kiore nanakia?’ (How fierce is the kiore?)