Annual bird counts show that banded dotterels have been declining on our braided rivers for many years. But there’s good news amongst the bad. A recently published analysis of longterm population trends, using data from 1962 to 2018, reveals just how big that decline has been – and how one riverbed in Mid-Canterbury is going against the trend, thanks to intensive predator control.

Colin O’Donnell and Joanne Monks for the Department of Conservation are the researchers involved and their paper has recently been published in Notornis the journal of Birds New Zealand.

“Banded dotterels (tūturiwhatu, Charadrius bicinctus bicinctus) are small plovers inhabiting New Zealand’s braided rivers, estuaries, seashores, and open country. They are considered Nationally Vulnerable under national threat listing criteria, but with uncertainty around the trend estimation.”

Habitat loss, disturbance and invasive species are key threats faced by wading birds. In New Zealand, braided rivers are the primary breeding habitat for several threatened wading birds, including tūturiwhatu.

“Braided rivers form extensive riverine habitats occurring widely in New Zealand, especially in the South Island and in Hawkes Bay region of the North Island, often from head water rivers in the mountains to lagoons and estuaries on the coast. These rivers are characterised by ever changing flowing channels and islands, and associated spring creeks, and adjacent flood plain terraces. Collectively, braided rivers cover >250,000 hectares and there are more than 300 rivers with braided stretches that support unique communities of plants and animals.”

Banded dotterels are characteristic of braided rivers, but their conservation status is uncertain.

“Banded dotterels occur throughout New Zealand, primarily breeding on sandy and shingle coastal beaches and dunes, inland shingle riverbeds, undeveloped drylands, on open alluvial flats, and occasionally on herbfields on mountain tops. Formerly, they commonly bred on lightly vegetated alluvial flats in many parts of the country before these habitats were largely converted to farmland.”

Nowadays, the main nesting habitats of banded dotterels are on braided rivers, primarily throughout the South Island, but also in parts of the North Island, particularly Hawkes Bay.

Tūturiwhatu are currently classified as threatened (Nationally Vulnerable) in the New Zealand Threat Classification System; meaning that the population (mature individuals) has been estimated at 5,000– 20,000 birds with a predicted population decline of 30–70% over the next three generations. Available data is considered ‘poor’ however due to because of the difficulties in obtaining national estimates of population size and obtaining robust estimates of population trend.

A further complication is that banded dotterels vary in whether – and how far – they migrate, so birds could also be subject to a wide range of threats away from their breeding grounds.

“Their movement patterns include sedentary lifestyles, through to intra-regional, national and trans-Tasman scales. It has been estimated that 60% of birds migrate to Australia each year, although the source of these migrants is primarily inland regions of the South Island, particularly the Mackenzie Basin.”

Many river and wetland birds are known to be declining. Time then, to find out just what the situation is for our ‘data deficient’ tūturiwhatu population.

“Braided river species including banded dotterels are threatened by a combination of factors on their breeding grounds, particularly predation by introduced mammalian predators and native avian predators, weed invasion, water and gravel abstraction, and dams, resulting in significant habitat loss. In addition, flood protection and other river control works are changing habitat characteristics, and disturbance from human recreational activities on rivers such as jetboating, four-wheel driving and fishing threaten nest and chick survival.”

Rats aren’t usually found in high numbers on riverbeds, but according to the authors, other introduced predators are a significant threat.

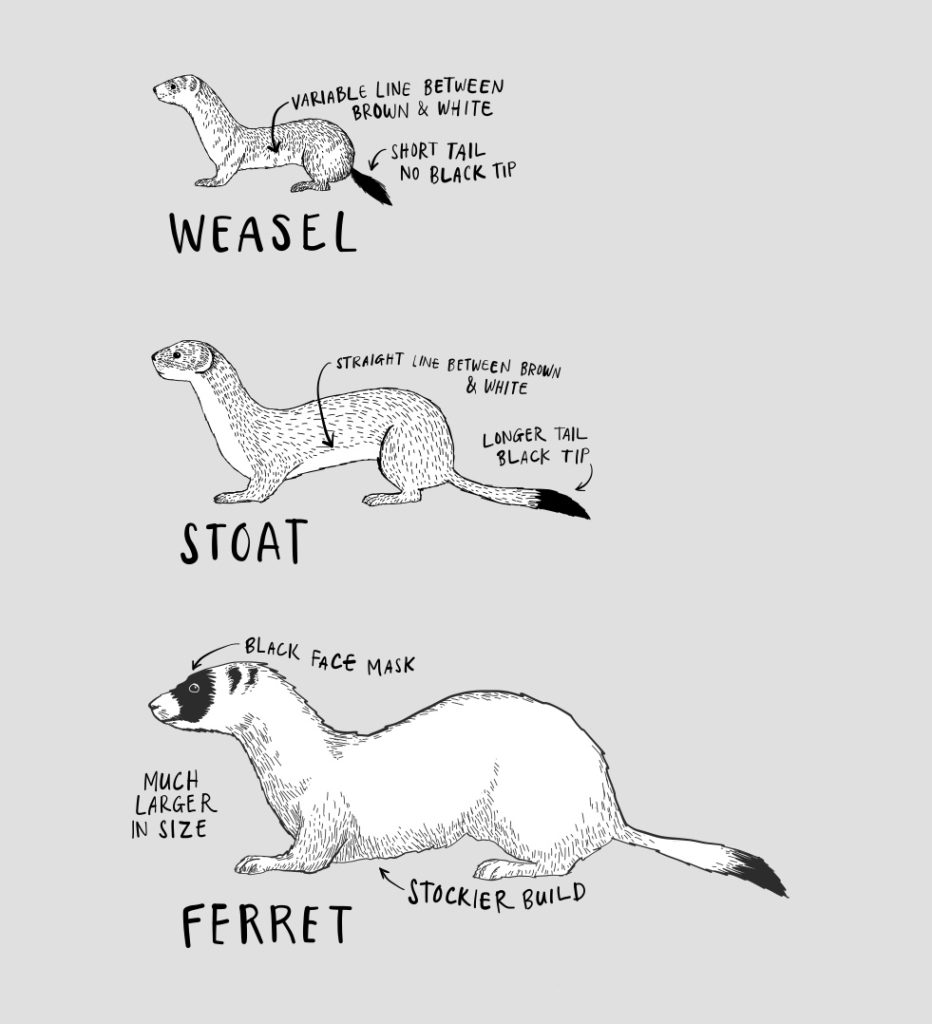

“Predation by invasive mammalian predators is the most obvious direct threat, with high levels of nest loss (>50%) particularly attributed to cats, stoats, ferrets and hedgehogs. Predator control, to increase productivity and survival of braided river birds, has been trialled using a range of standard trapping techniques on several rivers at a range of spatial and temporal scales. However, the effectiveness of control to date has been equivocal and confounded by the effects of natural flooding events.”

More research is needed to determine the most effective control strategies to reduce predation. With this study, O’Donnell and Monks aimed to fill some of the banded dotterel population data gaps.

“The objectives of this study are to:

- collate banded dotterel counts from all discoverable data sources on braided rivers across New Zealand;

- assess whether population trends are apparent in standardised counts of banded dotterels from surveys of braided river beds (1962 to 2017) and New Zealand winter counts (1984–2018)

- determine whether the few predator control initiatives on braided rivers result in increases in banded dotterel numbers; and

- use these data to estimate rates of population change and assess the appropriateness of the threat status given to this species.”

“We collated counts of banded dotterels from braided river bird surveys undertaken between 1962 and 2017 from as many sources as we could find (119 rivers). Most counts came from unpublished sources, often from the New Zealand Wildlife Service and Department of Conservation (DOC) file reports and from counts undertaken by community groups and organisations, e.g. Ashley/Rakahuri River Care group, Ornithological Society of New Zealand (OSNZ), Royal Forest and Bird Protection Society. We also collated nationwide counts from banded dotterel overwintering locations provided by OSNZ for the period 1984 to 2018.”

Counts were conducted on the riverbed breeding grounds during spring between late October and early December, when nesting was at a peak, birds were territorial and numbers most stable.

“A group of observers spread themselves evenly across the riverbed so the whole width was covered and walked down stream at the same pace, counting all birds seen as they passed them, and remaining in a line perpendicular to the flow of the river throughout the survey. The full width of riverbed encompassing all potential riverbed habitats was counted. Binoculars were used to identify and count birds accurately.”

Rules were used to minimise potential double-counting.

- birds were only counted when the observers passed them; the only exception was if a bird(s) flew off the river in front of the observer without circling back,;

- hand signals or radios were used to tell other observers on the line that a particular bird had been recorded as it passed up stream;

- one or two people were delegated to record the tally for bird colonies, in consultation with other members of the team.

“All-terrain vehicles or farm bikes were used along the margins of several small, dry riverbeds, and on large-flow rivers, jet boats and rafts were used to cross river channels to obtain full coverage. Rivers were generally surveyed in 10–20 km sections with different groups of observers counting simultaneously.”

Because not all birds would be visible or even present at any one time, these counts were of ‘relative abundance’, not a total population census.

“The surveys are based on the assumptions that the total number of birds counted is representative of the total minimum population using the river, that birds are not double counted, and that observer skills do not vary significantly over time.”

“We identified surveys that had been repeated at least four times (to allow trend analysis) in relatively standardised ways and generally covered the same riverbed reaches resulting in a subset of 33 rivers that could be used in our trend analyses.”

The researchers also collated river-scale variables for each river that might influence either the number of dotterels present or their population trends: presence of predator control, river flow size, flow modification and exotic weed cover. These factors potentially affect habitat area and quality and whether birds are subject of high or low predation pressure.

“Each river was classed as having no sustained predator control, partial predator control, or complete (sustained) predator control across the river reach. Predator control has been undertaken on rivers to varying degrees. Only the Eglinton River has had intensive sustained control since counting began. Three rivers now have sustained predator control, but not for the full time series of counts. The Ashley River and Hakatere Reach of the South Ashburton above the gorge (both partial) have only had sustained predator control since 2003.”

River flow was also recorded as that influences the ability of predators to cross onto river islands.

In total, the authors found 453 banded dotterel counts from 119 braided and shingle river reaches covering a distance of 3,240 kilometres of river in total.

“Most were in the South Island (103 rivers, 87%; of which 52% were in Canterbury, 13% in Southland, 8% each in Marlborough and Otago, 7% on the West Coast, and 1% Nelson). Far fewer were in the North Island (16 rivers; 12 in Wellington, 4 in Hawkes Bay). The sums of banded dotterel counts were 12,730 birds when tallying the most recent counts/river and 19,329 birds when tallying the maximum counts recorded per river.”

“Although banded dotterels were most widespread in the South Island, particularly Canterbury, the largest single concentration of birds was on the three Hawkes Bay rivers (a total of 2,851 birds counted on most recent counts).”

The majority (>50%) of dotterels counted on the most recent surveys were from just 10 (8%) rivers. Counts suitable for long-term trend analysis were only available for South Island sites. Widespread declines in banded dotterel count indices were recorded.

“The weighted mean annual rate of change across 33 South Island rivers was -3.7% p.a. (per annum), which equates to a 52.3% decline over 20 years (approximately 3 generations). We also detected a negative trend in dotterel numbers based on national winter count data, but of a smaller magnitude (-1.4% p.a., equating to a 25% decline over 20 years). However, trends in Australia, where c. 60% of banded dotterels over-winter, are unknown.”

Whether its a 52% or 25% decline, its significantly bad news for banded dotterels. But there was a glimmer of good news too.

“In contrast, a significant population increase was measured on the Hakatere Reach of the South Ashburton River, which has intensive, sustained predator control, and several predator trapping initiatives on other braided rivers and coastal areas indicate declines can be reversed with management if applied at an extensive landscape scale.”

“For the two rivers where sustained predator control was introduced part way through the dotterel monitoring period, on the Hakatere Reach, of the Ashburton River there was no significant trend in the period 1981 to 1999 prior to the implementation of predator control, but dotterel counts increased in the period 2004 to 2017 following commencement of predator control. In the period 1980 to 2002, dotterels on the Ashley River were declining rapidly; whereas post control numbers stabilised in the period 2003 to 2017.”

The authors found that although predation is a major cause of decline, there were relatively few examples of comprehensive predator control on rivers, that also have adequate dotterel monitoring or a long time series of counts, limiting the conclusions they could draw from the data they had.

“While many rivers have partial and patchy implementation of predator control, often biased towards catching a subset of predators or only controlling them for short periods, if the whole predator guild is not targeted simultaneously, and immigration of new predators is not limited from all directions, predation rates will likely remain high. In addition, efficacy of predator control interacts with other factors. For example, predator numbers are influenced by the abundance of rabbit prey in the surrounding catchment.’

Exotic vegetation cover and river flows also have an influence on predation

“Vegetated islands increase cover for predators, but high river flows limit the probability of predators being on islands in braided rivers, so flow reduction and increased vegetation cover will increase probability of predation. Thus, if flows are not maintained, or predator removal does not occur simultaneously with weed control, the benefits of predator control may be reduced markedly. In addition, if the full predator guild is not targeted, mammalian predators that prey on nests early in the breeding season may simply be replaced by avian predators, whose influence is high later in the breeding season.”

The Hakatere Reach in the upper Ashburton River was the only long-term example of effective predator control for banded dotterels found by the authors.

“This programme focuses on controlling all predators, including cats and common brushtail possums and removing a large black-backed gull colony that appeared following conversion of tussock grasslands to pasture in the wider area. This programme has seen a tripling of dotterel numbers over c. 15 years, suggesting that effective control programmes focussed on the whole predator guild can recover banded dotterel populations.”

Human disturbance is another threat which we need to act on, if we are to reverse the steady decline in our tūturiwhatu population.

“Our trend analysis indicates widespread steady declines in numbers of banded dotterels breeding on braided rivers in the South Island over the last c. 50 years. Banded dotterels are subject to a wide range of threats including very high levels of predation by invasive predators, human disturbance on breeding grounds, and habitat loss and degradation. Using the precautionary principle, the rates of decline on South Island braided rivers confirm the classification of Nationally Vulnerable using the NZ Threat Classification system. However, results suggest that the IUCN threat status for banded dotterel should be reclassified from Least Concern to Endangered.”

The full article is published in Notornis. Articles are freely available online one year after publication. Access may also be available through your public library.