It’s a bit like putting a message in a bottle – banding migratory birds and seeing where else in the world those specific bands are spotted by fellow birdwatchers. But it has a purpose that goes beyond curiosity about migration routes. Many migratory birds are declining in numbers. So where on their global travels is the mortality happening? And why.

Take the ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres), for example. Members of Birds New Zealand (Ornithological Society of New Zealand), have been catching and colour-marking on turnstones as part of a project undertaken for the Department of Conservation and reported back on their findings in a recent issue of Notornis (PDF, 803 KB).

“The ruddy turnstone is the third commonest Arctic-breeding shorebird occurring in New Zealand, after bartailed godwit and red knot. Numbers of turnstones in New Zealand during the non-breeding season (Austral summer) have declined from about 5,000 in the early 1990s to some 2,500 in the late 1990s/early 2000s, to 1,500 in the late 2000s. The reduction in numbers appears to be generally consistent across the country.”

Declines have also been recorded in Australia, where it’s considered ‘near threatened’.

“Elsewhere in the East Asian-Australasian Flyway (EAAF), turnstone numbers are also thought to be in decline, and the species was identified as a priority species for conservation efforts. Extensive deployment of geolocators in Australia has provided much information on movements of birds spending the non-breeding season in Victoria, South Australia and King Island, Tasmania. The present paper summarises records of movements of marked turnstones from and to New Zealand.”

Wetlands International (2020) currently estimates the East Asian-Australasian Flyway (EAAF) population as 28,500 birds, while other estimates suggest around 30,000 birds. Because turnstones are a migratory bird, with only some of the total population spending a short period of time in New Zealand, their plight has attracted little attention to date, as the authors explain.

“Since New Zealand supports <25% of the flyway population for <50% of its life-cycle its conservation status is not assessed by the Department of Conservation, it simply being categorised as a ‘migrant’. BirdLife International (2020) notes the population trend as ‘decreasing’, but currently lists turnstone as ‘Least Concern’; this assessment however is based on the total global population status.”

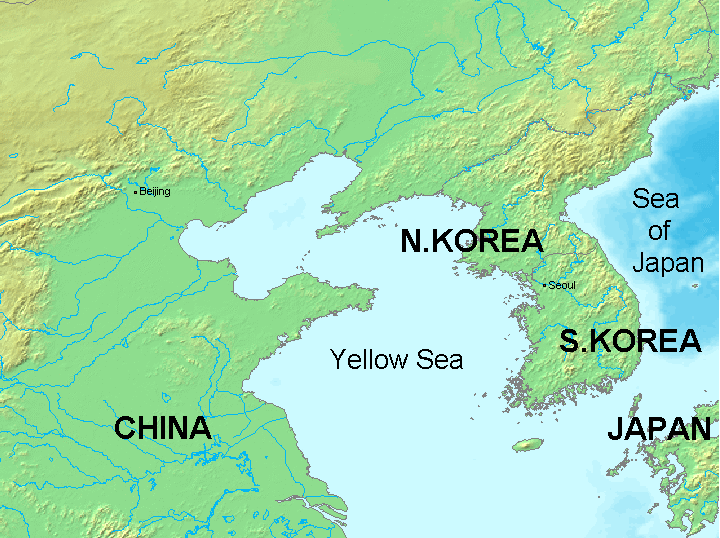

Declines in populations of many shorebirds in the EAAF are thought to be associated with habitat loss and degradation in the Yellow Sea, where the majority of the populations of many species stage on migration, but do New Zealand’s visitors follow this route? The Australian tracking studies offer some clues.

“Turnstones marked with geolocators in Southeast Australia mostly migrate northwards through Taiwan and the mainland Chinese and Korean coasts making little use of Japan – nonetheless large numbers of turnstones occur in Japan on northward migration and there are a considerable number of re-sights of birds marked in Australia. More use may be made of the Yellow Sea on southward migration.”

Turnstones have occasionally been banded at several New Zealand locations during the last 25 years.

“Relatively few turnstones have been marked in New Zealand, the total to 1 June 2020 being 216. Since 1996, 110 turnstones in the Auckland region have been marked with a geographic cohort plain white Darvic leg flag, and three birds with white over green leg flags in the Nelson region. Since 2009, a further 11 have been marked in the Auckland region with a white flag bearing an engraved three letter code allowing individual recognition. Individual colour band combinations have been used since 2004 on 50 turnstones in the South Island (24 at Motueka Sandspit, Tasman Bay and 26 at Awarua Bay, Southland) and 16 in the North Island (12 at Parengarenga Harbour, Far North, three in Manukau Harbour, Auckland and 1 at Manawatu estuary).”

Keen-eyed birdwatchers in Asia have spotted those same birds and reported their sightings, giving a brief ‘postcard’ of their international travels.

“Up to 1 June 2020, there had been seven records of individually marked turnstones banded in New Zealand re-sighted in East Asia and 35 records of birds with a geographic cohort flag. There have been 35 records in New Zealand of birds marked in Asia with geographic cohort flags. Birds marked in New Zealand have been reported from Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, and birds marked in Japan, South Korea, and mainland China were reported from New Zealand.”

One of the individually marked birds is known as W1BYWR based on its banding code. It seems to include an Australian stopover on its summer travels to New Zealand.

“The repeat reports of W1BYWR on northward migration in Taiwan in two years are notable as this bird was also seen on southward migration in Roebuck Bay, Australia. The only records of individually identifiable turnstones from East Asia being reported in New Zealand are two birds marked on 17 April 2018 at Chongming Dongtan National Nature Reserve, Shanghai, China which have been photographed at Riverton Estuary, Southland on 20 February 2019 (one bird) and on 16 March 2020 (both birds).”

These Asian records show that turnstones spending the non-breeding season in New Zealand may pass through East Asia on both northward and southward migration. But more about those trans-Tasman stopovers/excursions…

“There are 49 records of turnstones marked with geographic cohort flags in Australia re-sighted in New Zealand, with most occurring in the austral summer, but one bird in June is likely to have been an immature bird that did not migrate. Australian-banded birds have been seen from coastal sites throughout New Zealand.”

“Six birds individually marked in Victoria, one in South Australia and one on King Island, Tasmania have been reported from New Zealand, three being reported multiple times from the same site in different years during the austral summer. This suggests a high degree of site faithfulness, as has been found for non-breeding turnstones elsewhere, unless there is a food shortage in which case birds may move.”

When they leave New Zealand at the end of summer, some turnstones from both the North and South Islands are including another Australian stopover on the migratory journey.

“There are eight records of turnstones marked with a geographic cohort flag in the North Island and re-sighted in Australia, five records from King Island, Tasmania and three from Darwin, Northern Territory. Five individually marked turnstones from Awarua Bay, Southland have been reported from Australia. The re-sights of New Zealand-marked birds in Australia show that birds pass through on both northward and southward migration.”

Another bird with a unique individual identifying band is W1BYYW.

“The records of W1BYYW are particularly interesting as this bird was regularly reported on southward migration from Roebuck Bay, NW Australia, in five years but also twice from Victoria, although not during the same migration season.”

W1BYYW was also seen back at Awarua Bay on 22 October 2010.

So what do the sightings reveal about migration routes of turnstones visiting New Zealand?

“Data are limited, but it is clear that at least some turnstones visiting New Zealand during the austral summer are coming via East Asia, and Australia, and that some northward migrating birds are also passing through Australia on their way to Asia. It remains unclear what movements are taking place through the Pacific.”

Whilst information on routes used by turnstones when migrating to/from New Zealand is limited, a considerable amount is known about Australian turnstones from both marking and the use of geolocators.

“Birds generally migrate northwards along a relatively narrow front to Taiwan, and then pass through the Yellow Sea before moving to breeding grounds in the Russian Far East. The southward migration shows more variation, with some birds returning through East Asia, while others pass through the central Pacific.”

So what on this migration route could be having a negative impact on bird numbers?

“Australian geolocator data also suggest that turnstones are now migrating north earlier than previously, and that there may now be less birds staging in the Yellow Sea than formerly, possibly in response to habitat reduction and degradation. Numbers of turnstones at Saemangeum, South Korea decreased markedly following the closure of the reclamation seawall in 2006. However, habitat loss due to land claim has greatly reduced in China since 2018.”

Another possibility is that turnstones are being deliberately hunted in some parts of there migratory route.

“Trapping of turnstones for food has been recorded previously in Tuvalu (1961) and for sport on Nauru (1936, 2008), while they were shot for food in Hawaii (1902). It is unknown if trapping continues there and/ or elsewhere in the Pacific. In addition to deliberate harvesting turnstones are also caught accidentally in fish/crab traps on the Chinese coast, and possibly elsewhere.”

It has been suggested that the maximum number of turnstones that could be harvested sustainably (Potential Biological Removal) within the EAAF (East Asian-Australasian Flyway) was about 1,000 birds annually.

We still have a lot to learn about where turnstones travel when they leave New Zealand. It matters if we want to continue to enjoy these far-flying summer visitors.

“The current lack of detailed information about the migratory routes used by turnstones spending the non-breeding season in New Zealand is of concern in light of the continuing decline in their population, the cause(s) of which are unknown. There is an urgent need for a tracking study of the movements of turnstones that spend the non-breeding season in New Zealand to better understand their annual migrations, in particular potential use of the Pacific Flyway. This would assist in identifying possible causes of population decline.”

The article is available online in Notornis (PDF, 803 KB).