Not everyone can tell a mohua from a yellowhammer or even a kea from a kaka, but it would be a pretty rare New Zealander who didn’t know a kiwi when they saw one. It’s probably our most recognisable bird, but how well do we actually know our kiwi – really know them?

Note: We are re-sharing our articles. This article was originally published on October 11, 2020.

You probably know kiwi have a great sense of smell. But did you know the only bird with a bigger olfactory bulb (the scent centre of the brain) than the kiwi, proportional to the size of its forebrain, is the condor – a type of vulture. Condors are the largest flying birds in the Western Hemisphere with a huge wingspan (second only to the albatross) – so apart from an incredible sense of smell, condors and kiwi really don’t have a lot else in common.

Kiwi don’t have much of a wingspan at all. But they do have wings – vestigial ones. It’s a bit like the way we humans have a tailbone but, unlike our very early hominid ancestors, we no longer have a tail.

Kiwi are also the only birds in the world with external nostrils at the tip of their beak. Its nostrils and keen sense of smell help kiwi find food in the leaf litter, but there’s a downside too. Having nostrils so close to the food source means that kiwi get dust and dirt up their ‘nose’ when they’re out hunting. Those loud snuffling and snorting noises that kiwi make are the sounds of them clearing out the dust.

The kiwi’s beak is much more than just a very pointy version of a nose, however. It’s a vibration detector too. Kiwi have sensory pits at the tip of their beaks, which allow them to sense prey moving underground. It’s possible that feeling the prey’s vibrations may be more important to a hungry kiwi than smelling it. Instead, smell may be mainly used to explore their environment.

The beak has other uses too – as a probe and as a lever. The kiwi can even do a sort of kiwi headstand on its beak.

As it walks, the kiwi taps the ground with its beak, probing the soil and sniffing loudly. It can locate an earthworm up to three centimetres underground and pushes its beak deep into the earth. Using its beak as a lever, the kiwi moves it back and forth to widen the hole. Sometimes it uses its entire weight to drive the beak deeper, kicking its legs up – the kiwi headstand.

The kiwi isn’t the only bird in Aotearoa with a motion-sensing bill. Other probe-feeding birds, such as godwits and sandpipers, also have remarkably sensitive bill-tip organs to pick up prey vibrations (although they’re not known for doing headstands).

So kiwi are a bit like vultures and a bit like sandpipers. But surely their closest relative would have been the extinct moa? Actually no – probably not.

Scientists used to think that New Zealand’s moa and kiwi evolved from a common ancestor when New Zealand separated from Gondwana, then believed that kiwi were an offshoot of the emu lineage – they were all flightless birds after all. But DNA tells a different story. Enter the elephant bird…

After studying the DNA of Madagascar’s extinct giant elephant bird (Mullerornis agilis), scientists now believe it was the kiwi’s closest relative. Similarly, DNA studies show moa are older than kiwi in evolutionary terms – their ancestor split from the ratite line well before the common ancestor of kiwi and emus did.

DNA also shows the moa’s closest relative is the tinamou, a large group of small birds with weak powers of flight, that live in Central and South America. So the kiwi is related to a big flightless African bird and the moa is related to some small, nearly flightless American ones. How flightless birds even got to Aotearoa from Gondwanan Africa or South America is yet another mystery waiting to be solved.

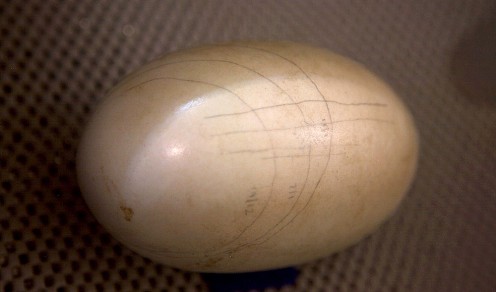

Then there is the huge kiwi egg – 20% of the adult female’s bodyweight! In proportion to its body size, the female kiwi lays a bigger egg than almost any other bird. In fact, kiwi eggs are six-times as big as normal for a bird of its size.

Sure the ostrich may lay the world’s largest bird’s egg, but it is actually the smallest in proportion to the mother – just 2% of her body weight. By comparison, the kiwi egg takes up about 20% of the mother’s body. A full-term human baby is about 5% of its mother’s body weight. A female kiwi can lay up to 100 of those enormous eggs in her lifetime. Be very, very glad you’re not a kiwi!

Although the female kiwi has to cope with an enormous egg, she is not the most heavily burdened female in the bird world. Small seabirds, such as storm petrels, have proportionately bigger eggs – up to 30% of their weight – and they have to fly with it on board.

Laying such a large egg can’t be easy, but there is an upside. No pain/no gain so the saying goes, and the upside for kiwi is that their young, once hatched, are very easy-care.

Most bird eggs are 35-40% yolk but the kiwi’s egg is a 65% yolk. The nutritious yolk produces kiwi chicks that hatch fully feathered and independent, and is so enormous that it continues to sustain them for the first week of life. By that time, chicks can provide for themselves and kiwi parents seldom have to feed their offspring.

Not only is the kiwi unlike any other bird – it’s also, in some ways, very like a nocturnal mammal, using its sense of smell to forage at night. Only about 3 per cent of bird species are nocturnal, and kiwi are the only nocturnal ratite. But most nocturnal animals evolve large eyes to gather what little light there is. Not so the kiwi.

Kiwi do not see in colour. Their eyes are very small and their visual fields are the smallest yet recorded in any bird. Most birds rely heavily on sight. The parts of a kiwi’s brain that serve vision are virtually non-existent, making their brains unique among birds. However, the parts of the brain devoted to touch and smell are large.

Kiwi are like honorary mammals in other ways too. They build burrows like a badger, where they sleep standing up. Their body temperature is lower than most birds, which range from 39ºC – 42ºC. The kiwi is more like a mammal, with a temperature between 37ºC and 38ºC.

The kiwi’s powerful muscular legs are heavy and marrow-filled, like a mammal, with skin as tough as shoe-leather. They make up a third of the bird’s weight. The skeletons of most birds are light and filled with air sacs to enable flight.

The eye sockets of most birds are separated by a plate, but in kiwi they are divided by large nasal cavities – just like most mammals. The kiwi’s sense of hearing is also well developed. Its ear openings are large and visible, and it will cock its head to direct its ear toward soft or distant noises.

Unlike most birds, which have one ovary, a female kiwi has two – like a mammal. If she produces more than one egg in a clutch, ovulation occurs in alternate ovaries. The chick emerges from its enormous egg as a mini adult, fully feathered and able to feed itself – which is very unusual for a bird.

Even the kiwi’s feathers are a bit like soft fur. A kiwi’s plumage is shaggy and hair-like, and it has cat-like, super-sensitive whiskers on its face and around the base of its beak. In most birds, feathers are connected by hooks or barbs that lock together and make it possible for birds to swim or fly without losing too much energy, even over very long distances. Because kiwi do not fly, their feathers have evolved a unique texture to suit a ground-based lifestyle. They are warm, shaggy and hair-like, hang loose and are much fluffier.

Kiwi love worms – but they eat a surprising variety of other foods too. Because kiwi live in diverse habitats, from mountain slopes to exotic pine forests, it is difficult to define a typical kiwi diet. Most of their food is invertebrates and a favourite is native worms, which can grow to more than 0.5 metres. Luckily for kiwi, New Zealand is rich in worms, with 178 native and 14 exotic species to choose from.

Kiwi also eat berries, seeds and some leaves. Species include totara, hinau, miro and various coprosma and hebe. Brown kiwi are known to eat bracket fungi and even frogs! They are also known to capture and eat freshwater crayfish/koura. In captivity, kiwi have fished eels/tuna out of a pond, subdued them with a few whacks, and eaten them too.

Their diet also means that kiwi can usually get all the water they need from their food. A juicy earthworm is 85% water. Droughts can be devastating for kiwi, however, especially if the ground is baked hard and they can’t access earthworms. When it does drink, a kiwi immerses its beak, tips back its head and gurgles down the water.

The image of kiwi as shy, retiring creatures is definitely a bit of a myth however. Kiwi are very territorial, can give a good kick with those meaty, strong legs and can run as fast as a human when alarmed. An adult kiwi can defend itself against most potential predators – but not dogs – and their young are much more vulnerable to the likes of stoats and cats.

Some of the survival issues kiwi face, happen before an egg even hatches. About 50% of all kiwi eggs fail to hatch – sometimes because of natural bacteria, sometimes because the adult bird is disturbed by predators. Of eggs that do hatch, about 90% of chicks are dead within 6 months – 70% of these are killed by stoats or cats, and about 20% die of natural causes or at the jaws and claws of other predators. Only 10% of kiwi chicks make it to six months. Fewer than 5% reach adulthood.

An average of 27 kiwi are killed by predators every week. That’s a population decline of around 1,400 kiwi every year (or 2%). At this rate, kiwi may disappear from the mainland in our lifetime. Just one hundred years ago, kiwi numbered in the millions.

But it’s not all gloom. We can and do help.

Approximately 20% of the kiwi population is under management. In areas under where predators are controlled, 50-60% of chicks survive. When areas are not under management 95% of kiwi die before reaching breeding age. Only 20% survival rate of kiwi chicks is needed for the population to increase. For proof of success check out what’s happening in the Coromandel, in the predator-controlled area, the kiwi population is doubling every decade.

And one last thing about kiwi. A cynic might say it also make them unusual in our modern world. Kiwi are among the few species that tend to live as monogamous couples and often mate for life. Kiwi relationships have been known to last over 20 years.

Find out more about our amazing kiwi at Save the kiwi.