Now that an increasing number of our wildlife-rich – but uninhabited by humans – offshore islands are becoming predator free, the conservation spotlight is turning to some of New Zealand’s inhabited islands. But predator eradication becomes more complicated when people are living onsite. Its not just about what’s technically possible. It’s also about what people want, how they feel about predator control and gaining majority support for conservation work that is carried out there.

Joanne Aley and James Russell recently surveyed the environmental and pest management attitudes of people living on Hauraki Gulf islands in a paper just published in Science for Conservation, a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation. Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed and resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature.

“To date, research on attitudes towards pest management has predominantly stemmed from ethical concerns about the welfare of target species, the impact on non-target species and controversies regarding the use of environmental toxins. Consequently, there has been a focus on attitudes towards particular pest management methods and pest species or both,” write the researchers. “Thus, although there has been some research on the attitudes of various stakeholders towards pest management, including policymakers and scientists, there has been no specific focus on inhabited islands or a broader context.”

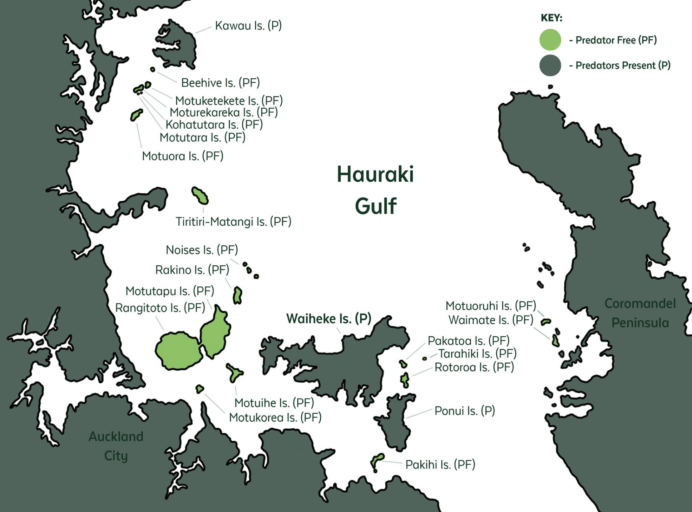

The Hauraki Gulf Marine Park (HGMP) lies on the east coast of the Auckland region and covers 1.2 million hectares of ocean. It includes 30 major island groups.

“Fourteen of the islands are classified as inhabited, some of which are free of certain invasive mammalian species that are encountered elsewhere in New Zealand. However, while invasive mammals have been successfully eradicated from many of the smaller islands in the HGMP, there has only been an ongoing dialogue regarding the eradication of mammals from larger, inhabited islands, with no implementation to date.”

“The aim of this study was to determine the attitudes of inhabited island communities towards the environment and pest management, particularly rat eradication, and to investigate the relationship between these attitudes. We specifically sought to understand the site-dependency of these attitudes among islands with different biogeographies, social profiles and pest management histories, and to contrast these attitudes with an adjacent mainland population. The findings of this study will help gain an understanding of the underlying drivers of attitudes towards pest management, and how these differ among islands.”

An anonymous postal survey of property owners was used to collect data.

“A postal survey was chosen over a web-based survey because three of the study islands are not connected to a mains electricity supply and it is possible that not all property owners have access to the internet. To ensure that we also reached property owners who were not permanently based at the physical property address on an island, particularly holiday home owners, addresses were derived from the Auckland Council rates database. This focus on property owners rather than the resident census population upon which comparisons are usually drawn may have introduced bias but was chosen because any future eradications will likely require property owner consultation and permission for the application of eradication treatments on their property.”

The four island populations surveyed were Rakino Island, Kawau Island, Great Barrier Island (Aotea Island) and Waiheke Island and the results were compared with responses from the adjacent mainland community of Auckland.

“Experience suggests that this progression to inhabited islands will bring new challenges to future eradications due to the added social influence and attitudes of people, particularly island residents. In particular, the eradication of rats by the aerial delivery of toxin, which is the only viable tool currently available for large islands, has been recently opposed both locally on Rakitu Island (Arid Island) and internationally on Lord Howe Island.”

“Since attitudes are invisible, inferences must be drawn from combined indicators of values, beliefs, norms and motivations to gain insight into them, with values relating to nature, self and others often being analysed to deduce environmental attitudes.”

The researchers define what they mean by values, beliefs, norms and motivations:

- Attitude: An attitude results from an individual’s ‘balanced evaluation of something, be it a person, object, concept, event, action etc and is reliably stable and ‘enduring’. An attitude is associated with three components: thoughts about something, feelings about something and behavioural intentions about something.

- Value: An individual’s values serve as guiding principles in their life, influencing their opinions and decisions. Although an attitude always has an object of focus, a value relates to no particular object. Values are for the most part stable and help us to make decisions when we are in conflict. Different values have different levels of importance, allowing them to be prioritised. An individual will then base their choice on this importance when faced with conflicting values. As a result, although people may share the same or very similar values, variation in the importance of these values will lead to individuals making different choices. Consequently, values are linked to a person’s core identity and are associated with their motivations.

- Belief: Beliefs are defined as convictions and are considered to be true, i.e. if a person believes something, then it is true for them. Since beliefs need not be correct, they are not based on factual knowledge and can often be formed from experience. Beliefs are extremely difficult to change and can remain unchanged despite opposing evidence.

- Norm: Norms are expressed as behaviours and therefore can be seen. In the case of environmental attitudes, this relates to what an individual does rather than what they say. Norms relate to how a person decides what to do based on what others are doing around them but may also be influenced by what the individual thinks is right or wrong. Norms are what a person ought to do. Social norms are established by society-sanctioning behaviours, either formally (e.g. a parking ticket) or informally with verbal or unspoken cues (e.g. standing in line). Personal norms reflect an individual’s sense of obligation, and within an environmental context reflect social responsibility.

- Motivation: Motivations that are relevant to environmental attitudes are associated with three particular values that describe how an individual relates self with nature or their concern for nature, others and self: biospheric, altruistic and egoistic. Biospheric values are where an individual’s concern is for nature and the environment overall, for nature’s own sake. Altruistic values relate to an individual’s concern for others, where the term ‘others’ can range from family to community to humanity as a whole. Egoistic values are triggered by how an individual is affected personally through self-interest and the avoidance of adverse consequences or the pursuit of benefits.

A total of 1190 of the 4422 surveys mailed out (26%) were returned completed.

“All four islands had above average response rates (28–40%), while the Auckland mainland had the lowest response rate (20%). More males responded overall (males, n = 632; females n = 545). The median ages of the survey respondents ranged from 59 (Auckland mainland) to 65 (Kawau), which is higher than for all areas in the 2013 census, reflecting trends in property ownership. In terms of ethnicity, New Zealand Europeans dominated for all study sites (83–93%), followed by Europeans (6–13%) and Māori (3–9%), with Pacific Islanders, Chinese, Indian and other ethnicities all being ≤ 3%, which is similar to the 2013 census. However, the Auckland mainland survey respondents had a higher proportion of New Zealand Europeans (83%) than the 2013 census results (59%), likely reflecting the stratified sampling for property owners of the Auckland mainland. Educational qualifications departed from the 2013 census results for all study sites, with lower proportions of people with no qualification or a diploma and higher proportions with a Bachelor’s Degree and above. Incomes for all study sites also differed from the census results, with a higher proportion of respondents having incomes > $50,000.”

So in terms of demographics, respondents tended to be older New Zealand Europeans, with above average education and income.

“We found that the four Hauraki Gulf island communities held varying attitudes towards the environment and pest management, despite their close geographical proximity to each other, with direct experience, history of pest management discourse and values having clear effects. At all five study sites, pro-environmental attitudes were strongly associated with biospheric environmental values and were also related to place attachment, through valuing the landscape and the environment.”

Island residents were found to be keen participants in conservation activities which influenced their attitude to the environment and level of environmental awareness.

“Pro-environmental attitudes were also reinforced by strong environmental awareness through conservation involvement, with respondents from all four island communities engaging with their own island’s environmental issues via on-island environmental organisations. This engagement was particularly strong for Kawau and Aotea, which have had historical pest management discourse. Conservation participation was greater for all locations than has previously been found for the wider New Zealand population, but respondents from Rakino, Aotea and Waiheke had greater participation than those from Kawau and the Auckland mainland. This may have been associated with the large number and variety of conservation organisations on these islands, particularly Aotea and Waiheke, which will provide a wider variety of opportunities for engagement.”

Strong positive environmental attitudes did not always translate into positive pest management attitudes. however. There were greater levels of uncertainty associated with attitudes towards pest management.

“The results do suggest, however, that pest eradication may have had long-term positive effects on the attitudes of inhabited island communities, with the residents of the only island from which rats have been eradicated (Rakino) having consistently more positive attitudes towards pest control. This was reinforced by the comments made by Rakino respondents, such as ‘Rats were eradicated from Rakino about 8 years ago – best thing that ever happened. The bird life is now huge’. The observed increase in bird life on Rakino since the eradication of rats reflects the findings of other research that predator removal results in stable and increasing bird populations and was also reflected by Rakino respondents in the higher level of acknowledgement of the benefits of pest management to threatened species translocations and ecosystem services.”

Most people supported rat eradication – but often with reservations.

“When respondents were asked to indicate their level of support for rat eradication directly, all five communities had considerably higher levels of support than opposition. However, the ‘depends’ category formed the second largest group in all five communities surveyed. Furthermore, while a strong endorsement of conservation and acknowledgement of pest management benefits were evident among the communities, so too were concerns surrounding eradication methods, particularly the impact of poisons on non-target species.”

The researchers conclude by recommending that further research is undertaken to understand what the respondents’ support is dependent on and the underlying factors that influence levels of trust in science.

The full report is freely available online, published on the Department of Conservation website:

A survey of environmental and pest management attitudes on inhabited Hauraki Gulf islands (2019)