Dr Carolyn King has spent a lifetime studying New Zealand’s introduced mammalian predators and is recognised as an international expert on mustelids. Meticulous historical and scientific research, along with a lifetime of practical field experience come together in her latest book, Invasive Predators in New Zealand: Disaster on Four Small Paws, just published and available as both an e-book and in hard-cover, through the publishers Palgrave Macmillan.

The book is part of the Palgrave Studies in World Environmental History book series and tells New Zealand’s story from pre-human times, when, by the mid-13th Century, the main islands of Aotearoa/New Zealand were the last large landmasses on Earth to remain uninhabited by humans, or any other land mammals.

“All of the introduced species described here are well equipped with teeth and claws, and all have caused untold damage to New Zealand’s native fauna over a turbulent few centuries,” the author writes. “While there are many good books and papers that touch on the different species and circumstances contributing to this sad story, I have aimed to bring all the threads of the saga together in one connected narrative.

‘Invasive Predators in New Zealand: Disaster on Four Small Paws’ is written in an accessible style and should appeal to both the general reader interested in conservation as well as those actively involved in predator control and research. Each individual paper that the book is based on contributes one piece to the invasive predator jigsaw. Dr King has joined all those pieces together in one volume, completing the jigsaw and allowing the reader to see the overall picture clearly.

“All chapters comprise current reviews of each topic at the time of writing, formulated for readers without experience of biological research. The result is far from a comprehensive survey of this huge subject, but contains enough clues to lead to sources of further information,” Dr King writes.

The book begins by giving a historical perspective – explaining how Aotearoa/New Zealand became the unique evolutionary laboratory that it was.

“New Zealand is the only emergent part of Zealandia, an isolated fragment of Gondwanaland, on which a historic series of three endemic faunas can be distinguished: (1) From 82 to 55 mya (million years ago), a subset of Gondwana species survived, including at least six species of dinosaurs, at least one crocodile and proto-mammals. (2) From 55 to 25 mya, a distinctly new endemic fauna was formed from new arrivals integrated with ancient survivors, as Zealandia rafted eastwards and gradually sank into an archipelago of low-lying islands. (3) From 25 mya to the end of the Pleistocene, earth movements and volcanic activity created the mountainous geography of modern New Zealand. Key fossil sites of the Miocene age (16 mya) preserve samples of tropical forest and fauna now long vanished. New alpine habitats <5 million years old are populated with endemic species evolved from forest ancestors as the land uplifted beneath them.”

“In the absence of any terrestrial mammals or snakes, flightlessness and large size evolved several times independently, associated with slow breeding and low mortality. The history of New Zealand explains why the endemic fauna were so uniquely vulnerable to the arrival of human and mammalian predators.”

So what makes some introduced species ‘invasive’, compared to the many other mammals, birds and invertebrates that have also been introduced over recent centuries without such catastrophic results?

“Not all mammals transported to New Zealand established self-sustaining populations, and not all of those that did have become invasive pests. As a broad rule of thumb, invasive species can be recognised as the ones that behave quite differently from their ancestors. Their wider distributions and higher numbers in their new countries can have unexpected and frequently damaging consequences. New Zealand is a textbook example of this selective process, so to protect our native biota, we have become a world leader in invasive species management.”

Other islands around the world have been invaded by predators too, but the nature of our historical isolation makes our predator issues particularly our own.

“Nowhere else has that particular combination of historical, geographical, biological and human circumstances that make the New Zealand story unique. Cats, mice and Norway rats are common problems on islands around the world, but no other country has such large populations of black rats, feral ferrets and wild (non-commensal) house mice as New Zealand has, or such huge numbers of brushtail possums (some 20 times more abundant here than in Australia, with very different relationships to forest trees and their animal communities).”

We can’t look to the rest of the world for a solution to our problems. In fact the world often looks to us. Our own predator eradication successes on offshore islands are world-leading. But in finding new solutions, the attempts and failures of our historical past must also be remembered. There are lessons to be learned.

“History is even more important in helping us to think about the future, because a detailed knowledge of how proposals of the past worked out, or didn’t, is needed to inform our much-needed critical judgement on which current proposals might eventually work, or not. History reminds us forcibly that nature is dynamic and that plans assuming that the future will be some minor variation of the present are at risk of encountering some unwelcome surprises.”

Dr King explains why individual predator species can’t just be considered in isolation. They’re part of complex communities and interspecies interactions.

“In the very unusual and artificial communities assembled over the history of human interference in New Zealand, many native populations have not only been invaded, they have been simply swept off the map. Therefore, predator-prey interactions cannot be interpreted in isolation, as in many older models; they are always part of a community, a web of interactions specific to a time, place and particular combination of species.”

One example given by the author in later chapters, is of the increase in stoat numbers after a beech mast.

“A stable future pest management policy for the inhabited expanses New Zealand must be based on knowledge of how the numbers of animals of all species are powerfully influenced, not only by the flexible parameters of their own population biology, but also by their interactions within the community into which they are adapted by their evolutionary history. For example, the damaging post-seedfall irruptions of stoats in southern beech forests are driven not by extra breeding but by sudden increases in juvenile survival. That in turn can be understood only in the contexts of the extra food supplied by the responses of not only wild house mice and ship rats, but also native seed-eating birds, to a sudden pulse in their own food supply.”

“Even though the key players in such communities in New Zealand are not always the same as those of anywhere else, the basic principles still apply here. So, the most useful branches of the massive theoretical base of mammalian predation biology for understanding events in New Zealand are those taking account of location-specific community-level interactions, habitat requirements and climate. We have discovered that the penalties of failing to do that are high. For example, the old idea of ‘the balance of nature’ has long been discredited but is still widely believed. It led directly to the tragic outcomes of Benjamin Bayly’s confidence in the ability of imported ‘natural enemies’ to control rabbits.”

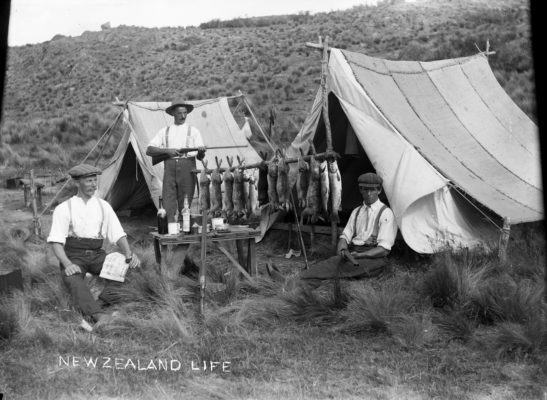

Benjamin Bayly was the government’s supervising rabbit inspector, responsible for combatting the ‘rabbit menace’.

“At least 75,000 ferrets were released in the South Island alone. Mortality among them was very high, especially in high country. The effect on rabbits could be useful under certain restricted conditions, not widely practised; open-country native fauna such as the buff weka were severely damaged or extinguished.”

“Over the decade 1883–1892, at least 7838 British stoats and weasels were landed in New Zealand. At least 25 shipments are known, on named ships, with their consignees and destinations. The number of animals landed according to official customs import data adds up to many more than are listed in the shipping records, so these are minimum estimates. The programme was driven against all objections by Benjamin Bayly, the government’s supervising rabbit inspector, until he was dismissed in 1889 and the government withdrew support for the programme.”

Some of our proposed future solutions carry a similar risk, if not carefully considered, with safeguards in place.

“The painful lessons of our past offer the world one overwhelmingly important cautionary tale, concerning the unpredictable dangers of implementing any self-perpetuating weapon. The possible gene drives of the future are generating both excitement and concern among pest managers, just as stoats and ferrets did in their time. But once released, neither can ever be recalled. No one can be fully confident of the ultimate outcome of such a policy, however carefully planned; and fast-moving current events would soon overtake any predictions from current knowledge. Still, the most obvious take home messages visible at present are clearly articulated at the end of Chap. 12.”

As well as telling the stories of how each cohort of invasive predator came to be here, how and why they’ve adapted so well and the impact they’ve had, Dr King writes about the present-day efforts to achieve an invasive predator-free future for our wildlife.

“The ongoing declines of New Zealand’s endemic birds, bats, lizards and frogs can be measured in distressing detail by every repeat survey and in every habitat. The groundswell of community concern for what has been lost—and worse, what is still at immediate risk of future loss—has now moved far beyond the decades-long protests of conservationists. Of course, there are multiple other contributing causes of environmental change, and we are increasingly recognising the importance of these, but much of the strongest conservationist focus has been on the alien introduced predators—especially rodents, cats and mustelids—which have had a devastating and pervasive effect on the numbers and distributions of the unique native fauna of New Zealand.”

“For the 250 years since the first Europeans landed in New Zealand, there has been no large-scale solution in sight, and not nearly enough money or political will to find one. Now, the agencies responsible for conservation policy have been stimulated to take real, expensive, government-sponsored action. New Zealand is facing the challenges posed by small predatory pests more seriously than ever before.”

“We know from hard experience that continuing with the pest control business as usual, by searching for more and better ways to kill individual pests in the hope of eradicating whole populations, can work spectacularly well on smaller offshore islands, but not wherever reinvasion is likely. So, the first lesson of intelligent pest control is, learn from history. We have to do that because it is not reasonable to keep on doing the same thing and expect a different outcome. Especially, we cannot continue to forget that introduced predators are not solely to blame for keeping native species out of radically modified landscapes where few natives can live.”

Dr King’s overall message is one of hope for the future, built on learning from the past.

“History can explain why PF2050 cannot get to where it wants to be from where it is now, but it also offers reasons to hope that new developments in understanding biodiversity loss, aided by as yet unknown advances in technology and radical increases in public engagement, could make that journey possible in the future. To do that, we need to know what did— and did not—work in the past. That is what this book is about.”

Check out Dr King’s book at the publisher’s website – chapter summaries are freely available online and the full text can be purchased as an e-book or as a hard copy volume:

Invasive Predators in New Zealand: Disaster on Four Small Paws Dr Carolyn King (2019)