‘Many hands make light work’, so the saying goes – although in the case of the Kapiti Coast community, it’s a matter of ‘many volunteers make radio work’. Conservation volunteers, other community members and innovative technology companies from Paekakariki and as far away as Great Barrier Island have all contributed time and expertise. Together they’ve erected a radio tower on a small island off Kapiti Island.

The radio tower is for remote monitoring of an extensive coastline SmartTrap network. It’s a fabulous example of cooperation and innovation – good old-fashioned community teamwork.

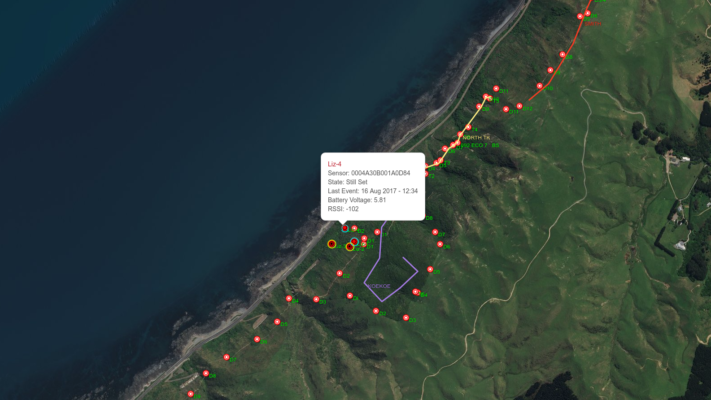

Tokomapuna Island (also known as ‘Airplane Island’) – a tiny island off Kapiti Island, is now standing sentinel over the Kapiti Coast, it’s newly erected transmitter a gathering and transmission point for information on the smart-traps across the water on the mainland. The transmitter, erected by local Paekakariki company Groundtruth, receives and transmits data on the LoRa radio network, alerting users on whether an individual predator trap has been triggered, using remote trap sensors developed by Great Barrier Island company Econode. Check out our earlier story about Econode here.

Also mounted on the radio tower is a webcam. It’s keeping watch too, over the adjacent Kapiti Marine Reserve, both to discourage poaching and as a real-time indicator of sea conditions for local kayakers.

The remote-monitored trapping programme is a project initiated and funded by the Kapiti Coast Biodiversity Project (KCBP) which, in turn, is funded by a grant from the Ministry for the Environment. Kapiti Coast Biodiversity Project group member Ngā Uruora Kāpiti Project (NUKP) is running the trial. NUKP has been carrying out volunteer conservation work on the coast for 20 years.

NUKP cares for 85 hectares of coastal escarpment between Paekakariki and Pukerua Bay. The land is owned by KiwiRail and QE II National Trust has a licence to undertake conservation projects. NUKP has an agreement with QE II National Trust to undertake planting, weed and pest control on the escarpment. Thus working with other organisations for the benefit of conservation is an integral part of how NUKP works.

In view of their group’s history of cooperative conservation, it’s no surprise that it was Ngā Uruora that first brought Great Barrier’s ‘Econode’ and Paekakariki’s ‘Groundtruth’ together. Using Econode’s remote sensors – one on each trap – and Groundtruth’s ‘TrapNZ’ free mapping and trap management software, NUKP’s volunteer trappers are now notified as soon as a trap is triggered and can respond to individual traps rather than checking the whole network on a regular basis. It’s a huge step up in efficiency, making the best use of valuable and limited volunteer time.

As a former economist, NUKP member Paul Callister, could see the potential for volunteer labour to be better used, capital better spent and productivity increased.

“It’s an example of the ‘internet of things’,” Paul says, “using technology in everyday processes and it came about through pure serendipity. The ‘Kapiti Mainland Island’ project joined up existing trapping groups,” he explains, “and that (being a larger organisation) meant there was the potential to invest in technology, to experiment and figure things out.”

Local company, Groundtruth was already known to the conservation volunteers and had worked with trappers at nearby Queen Elizabeth Regional Park (another member of the Kapiti Coast Biodiversity Project). Trappers there had previously been recording their trapping data using spreadsheets – switching to the free ‘TrapNZ’ phone app and software was a welcome advance.

“TrapNZ was set up in 2013 to encourage coordinated predator control in New Zealand,” says Daniel Bar-Even, who manages IT projects for Groundtruth. “It has funding from the World Wide Fund for Wildlife (WWF) and has a web interface with a smartphone app. It’s designed to be self-administering.”

The trap management system will already be familiar to many conservation groups.

“About 570 groups around New Zealand are currently using it,” says Daniel. “Since the Predator Free 2050 announcement, use has skyrocketed! There’s nothing else that really caters for urban community trapping.”

So how does it work?

“You log into the website or app and sync your latest data,” Daniel explains, “The software has interactive maps and can generate a range of reports. It can support any real-time radio enabled traps – smart-traps which have sensors and send notifications by email or text message.”

Combining TrapNZ with Econode seems like it was a great idea waiting to happen.

“We’re working in the same area,” agrees Daniel, “with interrelated projects. There’s an obvious connection. The Kapiti joint project was a test for us – a proof of concept.”

Enter the matchmaker – Kapiti Coast Biodiversity Project, via Paul Callister.

“My sister has a house on Great Barrier, where Econode is being developed,” Paul explains. “I got in touch with Econode and we arranged to meet in Wellington. We then set up an informal partnership with Econode, TrapNZ and the Kapiti Coast Biodiversity Project.”

Initially it was just an experiment to see how useful the combined technology would be.

“It’s incredibly useful,” Paul says. “The system tells you when a trap goes off, the time and potentially you can also match this to weather conditions. You can use it to collect useful information on baits. Volunteers can bypass untriggered sidelines when checking a trapline and it will help reduce volunteer hours.”

In fact, even Paul who helped bring about the collaboration, was surprised how useful it turned out to be.

“I thought it would be most useful for distant traps, but it’s actually useful for traps that are quite close too. If a trap is triggered near the village you can cycle down and fix it within 10 minutes, so the trap is quickly back in the network,” he says.

An added advantage of the instant notification system is that it allows volunteers to retrieve freshly caught specimens for research.

“Sue Blaikie, a local vet, carries out fresh autopsies to determine predation on lizards on the Kapiti escarpment as well as carrying out her own research project on weasels.”

The skinks and geckos are a particular interest for Paul who organises the reptile side of NUKP’s conservation and habitat restoration work.

Phase 1 of the smart-trap trial was deemed a success – but it had its issues too – not least of which was the limitations of the steep escarpment site itself. Under the shadow of the road above, radio transmission was difficult. Technology, for all its advances, still works best with a direct line of sight.

“It’s difficult with hills and dense bush,” Daniel Bar-Even explains, “There’s no cell phone coverage on the escarpment either.”

“But standing on the escarpment,” says Paul, “We could see Kapiti Island – and Kapiti could see us. We’re used to having island refuges for our wildlife, but here was a chance for an island refuge to protect the mainland.”

As it eventuated, however, it wasn’t Kapiti Island itself that ended up standing sentinel with a radio transmission tower, but nearby and much smaller Tokomapuna Island, thanks in no small part, to the enthusiastic support of local man Karl Webber, whose family are the Maori landowners of nearby Motungarara (Fisherman’s) Island, and 12 Ha of land around Waiurua Bay on Kapiti Island itself – the last remaining freehold Maori land on Kapiti. Tokomapuna (Airplane Island) and Tahoramaurea Island are also freehold Maori land but uninhabited, with Karl playing a Kaitiaki role on those islands.

In a further example of the serendipity of cooperation which has accompanied the Kapiti venture, Karl had already been in touch with Groundtruth personnel on behalf of another conservation group on the Kapiti Coast – a group that he himself had recently helped found – Guardians of Kapiti Marine Reserve.

“Kapiti Marine Reserve is the 4th oldest marine reserve in New Zealand,” says Karl. “It’s 25 years old and it’s been left to self-manage since about 2011. But just because DOC is not resourced to look after everything, doesn’t mean others can’t help it happen.”

‘Others’, in this case began with Karl himself and good mate Ben Joshua Knight.

“It started about 8-10 months ago with a conversation about looking after marine reserves,” says Karl, “Ben’s a hero. He set up a Facebook page, did the legwork and networking and we’ve had a lot of support from local government, the community board, police and so on. We were given $500 for our first public meeting and since then we’ve also used those funds for more meetings with speakers.”

Public recognition has been quick to follow.

“We won the ‘heritage and environment’ and ‘supreme winner categories at the recent Wellington Airport Kapiti Community Awards. There’s $1000 for each award, with regional finals to come in October.”

The new group has also been getting to know other Kapiti conservation organisations.

“We met other environmental groups and joining all the groups together has been a wonderful collaboration,” says Karl. “We come to each other’s meetings and it’s really encouraging.”

The Guardians of Kapiti Marine Reserve were keen to set up a webcam to monitor offshore, which is why Karl was talking to Daniel at Groundtruth around the same time as Paul Callister’s group was discussing a radio aerial – two projects ideally suited to becoming one multipurpose aerial.

As a local Kaitiaki, Karl approached a Maori Trustee about erecting the aerial on one of the uninhabited islands off Kapiti.

“The Trustee had no objections,” says Karl. “I also talked to a couple of other owners.”

Tokomapuna, the island chosen, is surrounded by strong currents, which help to protect the island and aerial from human interference – but also made access difficult for getting the aerial and other gear across in the first place.

“Installations are generally solar-powered,” says Daniel Bar-Even, “and a big part of the equipment is the solar power system.”

“Karl used his boat at his own cost,” says Paul Callister, “He launched the boat off the beach at Paraparaumu. The team at Groundtruth also donated many hundreds of hours and there’s also been huge support from people at DOC. There has been an amazing level of collaboration.”

For most of the last 10 years, Karl has lived on Motungarara (Fisherman’s) Island, another small island in the whanau-owned group – “my family signed the Treaty there,” he says – so trips back and forth across the water to the Kapiti mainland are a common occurrence for him.

With seas on the rough side during the construction period, Karl ended up landing some of the equipment on his home island, Motungarara, where access is easier. He later anchored his boat off Tokomapuna and used a kayak to paddle in.

“I helped Dan (from Groundtruth) install the solar panels, mast, radio and wifi, batteries and other electronic equipment,” he says. “That’s all done now, so the next thing is to check that the mustelid and rat traps are working and linked in. The Guardians have a camera at the base of the aerial with a battery box set up and we’ve gone for funding to install a starlight camera on the post to connect to the network.”

Karl also has a couple of monitored mustelid traps set up on whanau-owned land at Waiorua Bay at the north end of Kapiti. If funding is successful he hopes to have the new camera setup before December. With good visibility in low light levels – even at night-time – and a potential 360 degree view of the marine reserve, the camera should deter poachers, aid kayakers, waka ama and Search & Rescue and perhaps even help put Kapiti Coast and its large marine reserve on the global tourist map.

So as a new aerial keeps watch over the marine reserve and coastline, everyone is benefitting in Kapiti – except for unwelcome predators on the escarpment. Paul Callister is hoping he’ll be seeing a lot more skinks and geckos there in future.