WARNING: [stomach] contents may disturb sensitive readers.

When Jamie McAulay opens his mail in the morning he often finds “a lovely, delightful, maggoty mess!” Jamie is a Masters student in the University of Otago’s Zoology Department and lately conservation volunteers and professional trappers from Nelson to Fiordland have been posting him their dead stoats.

‘How kind’, you might think, ‘another smelly rotting corpse’ – and goodness knows what the postal service thinks – but Jamie is deeply appreciative of the efforts of his stoat suppliers.

“Volunteers from Friends of Cobb’ and ‘Friends of Flora’ check the traps, collect the rotten stoats, carry them down the mountains in their backpacks, put them on ice and post them to me. Then I boil up the bones and chemically extract the collagen. You can imagine how good it smells!” he adds cheerfully.

Jamie also extracts the keratin from stoat claws. It’s all part of his research into the diet of alpine stoats. He’s collecting stoats from the alpine zones of four different national parks: Nelson Lakes and Kahurangi at the top of the South Island where the volunteer groups are his suppliers and Fiordland and Aspiring in the lower South Island, where professional trapping contractor ‘Mammalian Corrections Unit’ collects and sends their stoat catches to him.

“Mammalian Corrections have been a huge help in getting stoats,” he says.

Jamie first became interested in the impact of stoats as alpine predators when he was working for the Department of Conservation on a rock wren project.

“We had cameras on nests which we would check. We’d see the eggs, then the chicks hatching, then the chicks getting their pin feathers. But nest after nest was being nailed by stoats.”

Research gaps

There are big gaps in the research on predators in the alpine zone and he’s hoping his research will shed some light on exactly what’s happening.

“The alpine zone has traditionally been seen as safe,” says Jamie, “But species-specific monitoring has shown that’s not the case. Rock wren, kiwi, takahe, kea and kakapo have all shown signs of stoat predation. There’s a huge alpine zone that needs protecting,” he adds, “700,000 hectares – but we don’t have the tools. We know about bush trapping and if it works okay in the bush, we do the same up in the tops.”

Jamie is working with the Terrestrial Ecosystems Unit at DOC, with Jo Monks at DOC, Deb Wilson from Landcare Research and Phil Seddon from the University of Otago’s Zoology Department as his Masters research supervisors.

“I’m trying to discover more about where and when predation risk is high in the alpine zone in order to target where to put the money to make the most difference,” he explains. “What drives the chance of a stoat getting something? My research looks at diet – how it varies across different areas of the South Island and in different seasons. I’m also looking at what different stoats eat,” he adds. “Are some stoats specialising (in native species) or are they all eating the same things? Does their diet vary over time – with events such as tussock masts – does it vary in different places?”

Last meal

If the stoats are sufficiently ‘intact’ when retrieved from their traps and sent to his lab, Jamie can tell what their most recent meal was by looking at their stomach contents. It can be a shockingly vivid revelation.

“Of the nine stoats I got in January from Nelson Lakes, seven had intact stomachs,” Jamie says.

“And four of those seven stoats had eaten skinks. One stoat had 19 skink feet inside it and that only represented the last meal of that one stoat. The long-term predation must be incredible!”

Jamie consulted experts to see if they could identify the species of skink that had been eaten.

“The skink people were unsure, so the EcoGene Laboratory in Auckland is going to try and genetically ID the feet.”

Alpine stoats are known to eat mice, rats and – surprisingly, hares. Possibly they prey on leverets, rather than adult hares, but either way, stoats are very effective predators. While the introduced mammals can be considered ‘natural prey’ for stoats, some stoats clearly aren’t sticking strictly to the standard diet sheet.

“A monitored (native wildlife) population will be doing okay, then suddenly it will get nobbled,” says Jamie. “But does that mean we need to control all the stoats or just some (rogue) individuals? A lot of ground weta get eaten but they have quite a patchy distribution. So where there are not so many weta, does that mean there’s a bigger chance birds will get eaten?”

There are plenty of questions to be answered, but looking at recent stomach contents only gives a limited picture of very recent diet.

“We’ve looked at 50 stoats from over the South Island,” he says. “It’s hard work – but the last meal is not that meaningful. Of those 50 stoats, if 1/20 had eaten hare for their last meal, does that mean all stoats eat hare for 1 meal in 20 or does it mean that 1 in 20 stoats lives mostly on hares?”

Gutting gives an extra level of calibration because it can be compared with past studies, but Jamie hopes that biochemical assays will give a broader view of stoat predation over a longer period of time.

You are what you eat

The biochemical technique used is called stable isotope analysis. Stable isotope analysis looks for chemical signatures of different animals from their tissue such as keratin and bone.

“If we can identify chemical signatures for stoats and their prey items, we should be able to tell which prey category or food chain level the stoat has been feeding on,” Jamie explains.

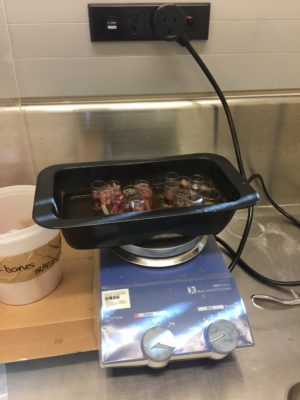

The first samples have just been submitted to the Chemistry Department at Otago to be put through their mass spectrometer – the product of all that boiling up of bones. As well as extracting collagen from bones, Jamie has also extracted keratin from stoat claws.

“The collagen and keratin mean that I can look at two different timeframes,” he explains. “Keratin is inert so the chemical makeup is from just the period when it was grown, but bone is constantly replenishing, so several years of diet are represented in bone collagen.”

Samples have also been obtained from prey species.

“Mice and hares were killed to get samples from their muscle tissue and for weta, a sample of exoskeleton was used. A very tiny (12 millionths of a litre) blood sample was taken from small birds,” says Jamie. “It’s considered more ethical to take blood from birds than to take a feather sample – less chance of longterm harm,” he explains.

He also regularly posts his daily activities on social media, to share his research process and experiences.

“I know it’s a bit of a jump to trust biochemical assays,” Jamie explains, “And it’s so powerful. I want to bring people on the journey so they’ll trust the results. I think it’s cool that you can get so much information from bones.”

On the day we spoke, for example, he was preparing collagen to be freeze-dried.

“First you demineralise the bone in hydrochloric acid, then you put it in the oven to denature. The collagen then goes into solution and you freeze-dry that. It comes out as this fluffy white polystyrene stuff,” he explains.

It sounds macabre, gory, sinister, fascinating… and smelly.

“It’s really cool,” says Jamie, “But it’s so hard to study stoats. Their territory can be a square kilometre and a few animals can do a large amount of damage, so you need to catch a lot of stoats over a large area.”

And as many volunteers will agree, catching stoats is never easy.

Jamie is full of praise for the local DOC staff, contractors, and ‘Friends of Cobb’ and ‘Friends of Flora’ volunteers who have been helping him.

“I leant so much about trapping by spending a week in a hut with them, asking questions.”

If all goes well, Jamie hopes to have information of his own to share once his research is complete. But in the meantime, there are gruesome parcels to be opened, bones to be boiled… work to be done.

Follow the progress of Jamie McAulay’s research on: Instagram