From suburban backyards to the steep south coast, Predator Free Wellington’s field staff are methodically clearing the capital city of rats. Curious about their day-to-day grind, Andrew James joins the team to see what it takes to evict predators and protect native wildlife in the city.

7:58 am

The depot sounds like a house party: loud chatter, clinking mugs, and a near-chaotic buzz. This former petrol station is home base for Predator Free Wellington (PFW), the crew working to evict rats from New Zealand’s capital.

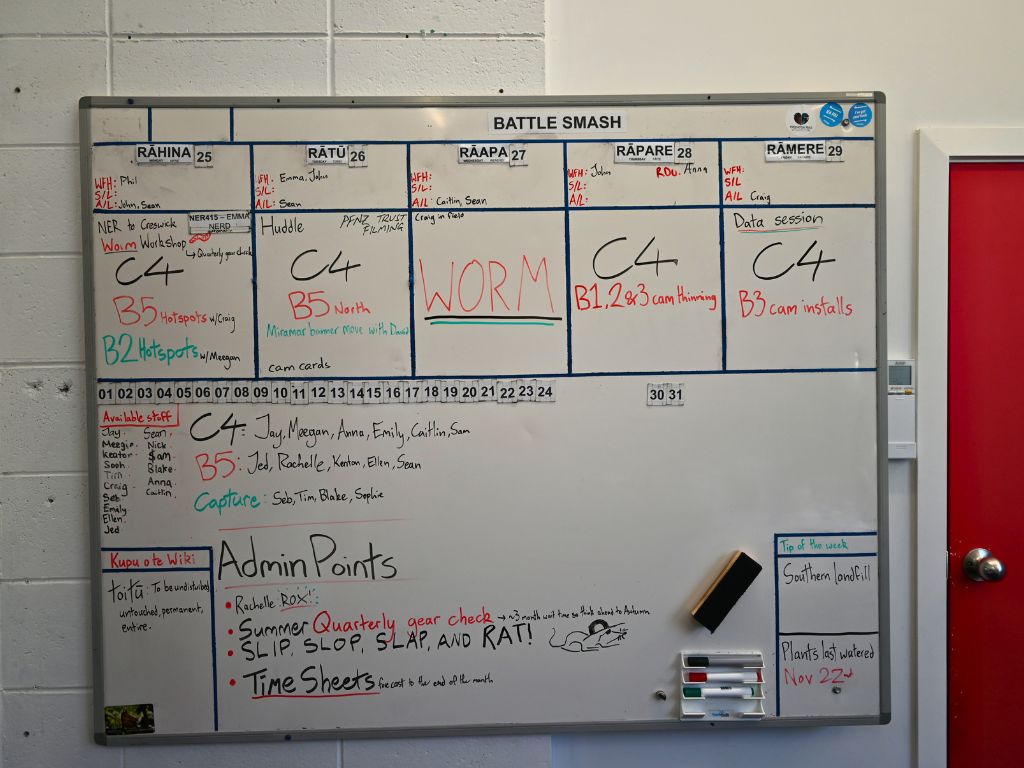

Jed, a field supervisor, hushes the room with a plan for today — some teams are servicing traps and bait stations, and others are following up on rat sightings. This afternoon, they’ll prepare for tomorrow’s assault on something called “The Worm.” Sounds like a sci-fi villain.

After the briefing, the meeting room empties in a flurry of backpacks and boots. Next door, in the garage, rangers load supplies. The room is packed with tools of the trade: traps soaking in peanut oil, buckets of bait and bulk batteries.

There’s a small museum of “field finds”: weird objects found in the bush, including a pair of plastic flamingos and an eclectic Lego collection. An enormous plastic sack of peanut butter is on the floor, waiting to be decanted into little plastic jars.

With packs full, each team huddles and plans the day, then throws their hands in and cheers. The ritual hints at the culture here; clearing traps is repetitive, solitary work, but the team makes it feel like a larger mission.

9:20 am

The 18-strong team pack into half a dozen utes to roll out. I’m riding with Jay, a field supervisor who’s been on the team since 2019. Before that, he worked in predator control on Rakiura (Stewart Island).

As the ute climbs the winding streets behind Oriental Parade, Jay explains how PFW has sliced the capital into blocks, with many given nicknames like “Palliser Palace” and “C4”. The block names are practical but carry a hint of spy-thriller.

When I ask about “The Worm,” Jay laughs. It’s not an alien but a near-vertical section of bush on the south coast. Rats love it. Rangers? Not so much. Tomorrow, the whole team will head there and refresh everything.

9:41 am

We park and head into the bush to service a bait station. It’s tucked away under a canopy of kawakawa, marked by a small fluorescent flag that’s tough to spot.

Jay unlocks the bait station with a special tool: no rat nibbles, just silvery snail trails. He replaces the bait, spreads peanut butter and hammers in a chew card, and logs the visit into Trap.NZ.

Servicing a station is best practice; keeping bait fresh makes it more attractive to rodents.

As we emerge from the bush, it’s nearly time for our first “appointment”.

9:58 am

As we head towards the house, Jay eyes a playground slide. “Why not?” he shrugs, climbing to the top. It’s a brief moment of fun, but it shows the PFW vibe: a mix of hard work and good humour.

At 10:00 sharp, we knock. The homeowner smiles as she leads us to her backyard, where two stations sit between compost bins and lemon trees. Rats are known to chew citrus skin, leaving the fruit skinned while still dangling from the tree. With rat control, this homeowner will enjoy a summer of juicy lemons.

It’s the same deal as in the bush—bait refreshed, chew cards replaced, everything logged.

10:09 am

The gate at the next house has been left unlocked. It clicks open, and we’re in.

All residents involved have given permission for devices to be on their property and regularly accessed; they clearly trust the team, which makes the whole endeavour possible.

Jay vaults over a handrail and vanishes into a fig tree. Without the precise notes in the system, it’d be impossible to find this humane DOC 200 trap.

Jay resets the trap and emerges with a grin. “Still no rats. That’s what we like to see.”

11:01 am

With no appointments for an hour, we dive into the thick, steep bush behind Oriental Bay.

With a dead drill battery, it takes a good while to remove all the screws that keep the station secure. “Kākā are a big reason for the mahi,” Jay says, “we don’t want them getting in here.”

Wellington has seen native bird counts skyrocket in the last decade: 243% increase in kererū, 170% increase in kākā and 93% increase in tūī. This recovery is thanks to Zealandia, community predator control groups, and with PFW’s expansion across the city native bird encounters are expected to continue to soar.

No sign of rats here. Still, Jay refreshes the station. A riroriro (grey warbler) calls overhead as we clamber back uphill.

12:24 pm

Lunchbreak on a bench at Oriental Bay. A seagull eyes my sandwich, but I’m not sharing. We’ve got an afternoon of appointments, and if there’s more bush-bashing and hill-scrambling, I’ll need the energy.

1:32 pm

The last house of the day backs onto the bush, with six bait stations scattered across the property. Some are easy to reach; others require mountaineering skills.

At the third station, Jay digs through thick foliage. Dogs bark as a man appears on the deck above; the resident has returned home.

At first, he’s startled by the sight of strangers in his backyard, but when he realises we’re from Predator Free Wellington, he waves it off: “All good guys, carry on!”

Moments like this show the trust the project has earned. People are stoked to see this work happening.

3:19 pm

As we head back to the depot for a debrief and data crunching, Jay reflects on the day. “It’s not just about clearing predators,” he says. “It’s about changing how people see conservation. Every backyard we clear is a win for the birds — and for getting people on board.”

Wellingtonians are seeing conservation happen right in front of them. It makes it concrete when it’s happening “right here”, not “way over there” in the bush. And they’re enjoying the benefits: more kākā and pīwakawaka and fewer rat-induced kitchen floods or chewed-out insulation.

Back at the depot, the team is already discussing tomorrow’s mission into The Worm. It’s tough work; my knees are already sore. But the rangers know that with every trap they set, Wellington’s future gets a bit brighter – and a lot less ratty.