When it comes to introduced predators, we hear a lot about their impact on birds, bats and lizards. But New Zealand’s native fish are also on the menu. The kōkopu lays its eggs on land, making them an easy target for rats, mice and hedgehogs. A mix of muscle, native seedlings and a whole lot of rat traps are helping keep them safe.

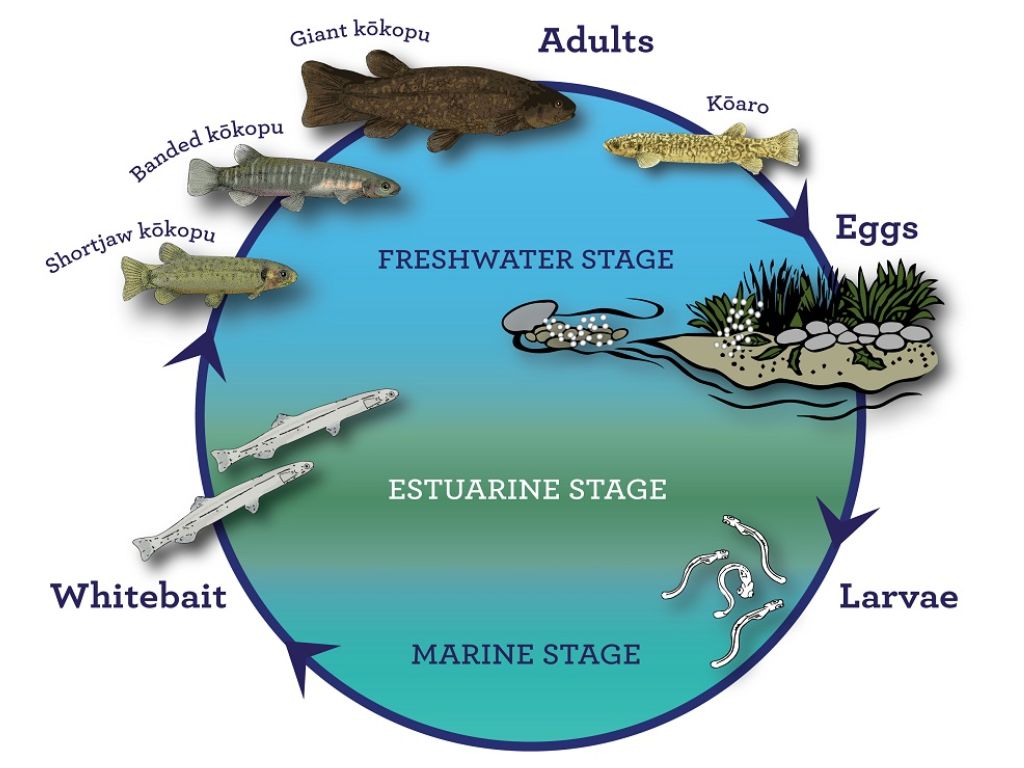

You might be more familiar with kōkopu in their juvenile form: whitebait, as in whitebait fritters. But these galaxiid species are as special, unique and threatened as kiwi, kākāpō and takahē.

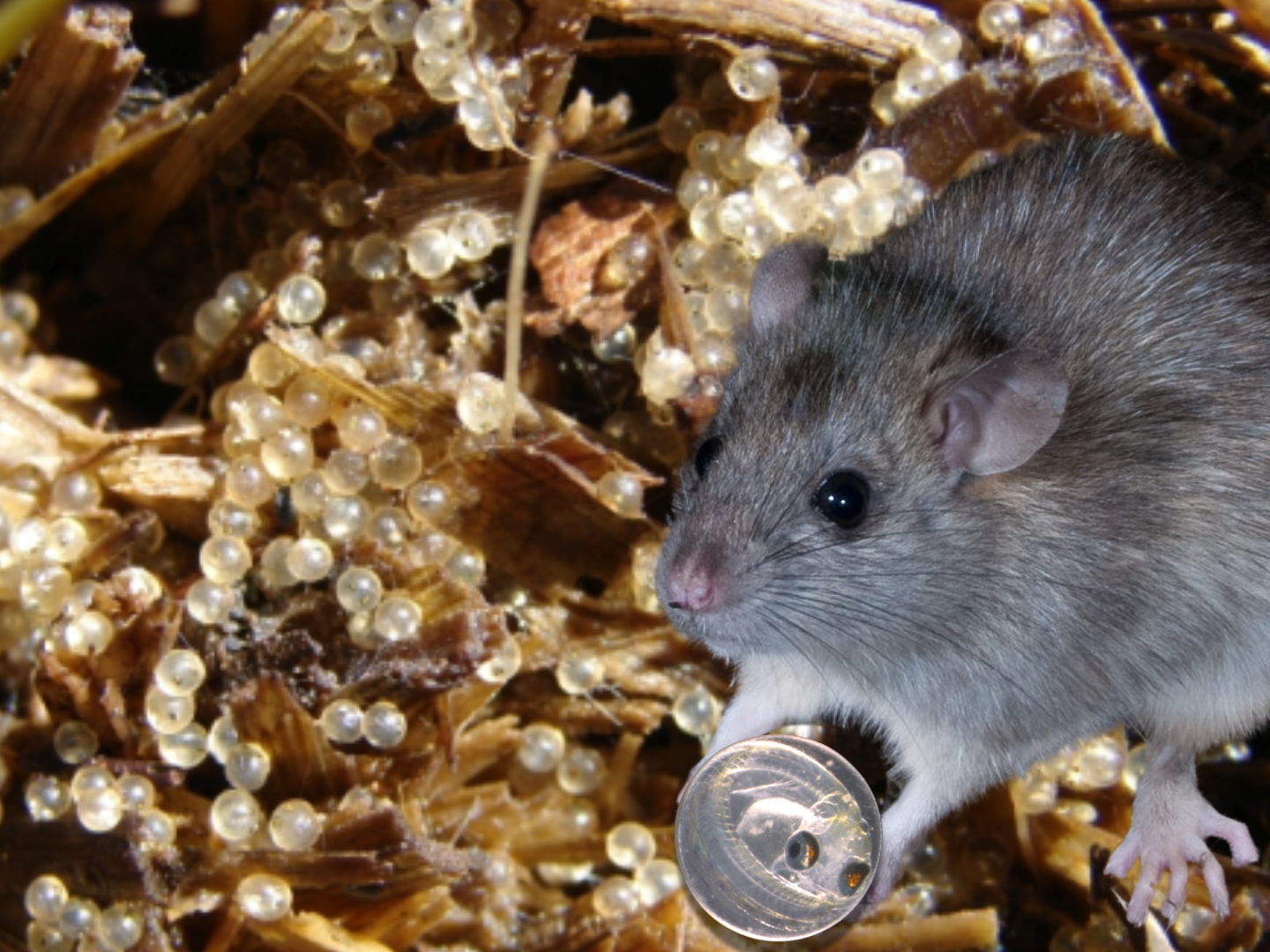

While humans prefer to eat them with a squirt of lemon and salt, rats, mice, and hedgehogs have a taste for kōkopu eggs, eating them when they’re left exposed on stream banks for weeks at a time.

But in Auckland’s South Titirangi, a community believes kōkopu are friends, not rat food. The South Titirangi Neighbourhood Network / Titirangi Urban Sanctuary (STNN) has a job as big as its name: protecting these native fish that live in their local stream in partnership with the Mountain to Sea Conservation Trust – Whitebait Connection.

Setting up the perfect real estate

Since 2021, volunteers have planted nearly 2,000 native seedlings along the bank of the Paturoa Stream, home to the giant kōkopu, the largest of the Galaxias species.

These fish thrive in cooler, shaded waters. When the giant kōkopu spawn, they lay their eggs in the grasses and vegetation on the bank, where shade, high moisture content, and humidity provide the optimum conditions for hatching.

But it’s not all planting trees. The STNN team has also been fighting off weeds and removing predators from the area. Over the last year, hundreds of rats, possums, hedgehogs and mice have been removed.

STNN co-chair Bruce Inwood is optimistic about their efforts.

“Early indications are that our weeding, planting and pest control work is positively impacting the ecosystem across the South Titirangi peninsula. And that will improve catchment health for all sorts of species,” he says.

DOC recently caught a rat on a trail camera eating shortjaw kōkopu eggs in Northland.

“Which is exactly what can and does occur in streams without intensive predator control in place,” says Wai Connection and Whitebait Connection Auckland regional manager Briar Broad.

“Thankfully, there have been no visual sightings from us of predation by pest species at Paturoa, which is more reason to continue the pest control that is in place,” she says.

Why care for kōkopu?

Bruce explains that giant kōkopu play a major role in keeping the aquatic ecosystem healthy and balanced.

“They’re an incredibly important part of the food chain, feeding on aquatic and terrestrial insects, freshwater crayfish and spiders. They also help redistribute nutrients to the water through their waste, which helps aquatic plants and algae continue to grow.”

Giant kōkopu have a fascinating lifecycle.

“While adults live upstream, their larvae are washed into the ocean, later maturing into whitebait that seek out freshwater streams to return to — not necessarily the one they spawned from.”

They must live in habitats that allow fish passage, i.e. the ability to move between salt and freshwater to complete their lifecycle. According to Bruce, a handful of sightings of young giant kōkopu have been above the fish passage.

“That’s a promising sign as it indicates recruitment into the stream.”

“Our dream is that eventually there are so many giant kōkopu that some have to find somewhere else to live, and we impact neighbouring streams,” says Bruce.

With continued habitat restoration, including more planting days, ongoing pest control, and fish monitoring, STNN and their supporters are laying the foundation for that dream to become a reality.

What started in 2016 with a group of just four neighbours teaming up to weed and replant local areas is now a growing network of more than 450 households working towards restoring biodiversity in South Titirangi.

Here’s how you can help:

- Set traps near streams to keep predators like rats and mice in check.

- Plant native vegetation along stream edges to provide leafy shade.

- Protect streamside vegetation by fencing it off from livestock.

- Keep pollutants like paint, chemicals, and rubbish out of storm drains.