New Zealand’s pekapeka (bat) is about the size of an adult thumb. Virtually silent, except for occasional high-pitched squeaks, they emerge under the cover of night and fly at speeds up to 60km/h. So, when it comes to monitoring them, how hard can it be?

To monitor bats, one must act like a bat.

This means swapping daylight hours for nighttime vigils, hanging out in forests with tall trees by waterways, and learning bat language.

Emma Naylor is a budding detector of pekapeka-tou-roa (long-tailed bat).

She spent many sleepless nights tracking the elusive mammals while working as a predator free apprentice at Ecoworks in Tairāwhiti (Gisborne).

The Ecoworks team has been monitoring bats since 2010, using spectral recorders, thermal scopes, and hand-held bat detectors.

Tools of the trade: spectral recorders

Bats fly and hunt using echolocation, emitting ultrasound clicks that bounce off objects, much like radar. Humans can’t hear these clicks, but spectral recorders can.

“We put these spectral recorders, or acoustic bat monitors, near waterways, rivers, ponds and tall trees where we think bats are roosting.

“Bats in flight are silent to humans, but they actually make a lot of noise.

Positioning the recorders is an art form in itself.

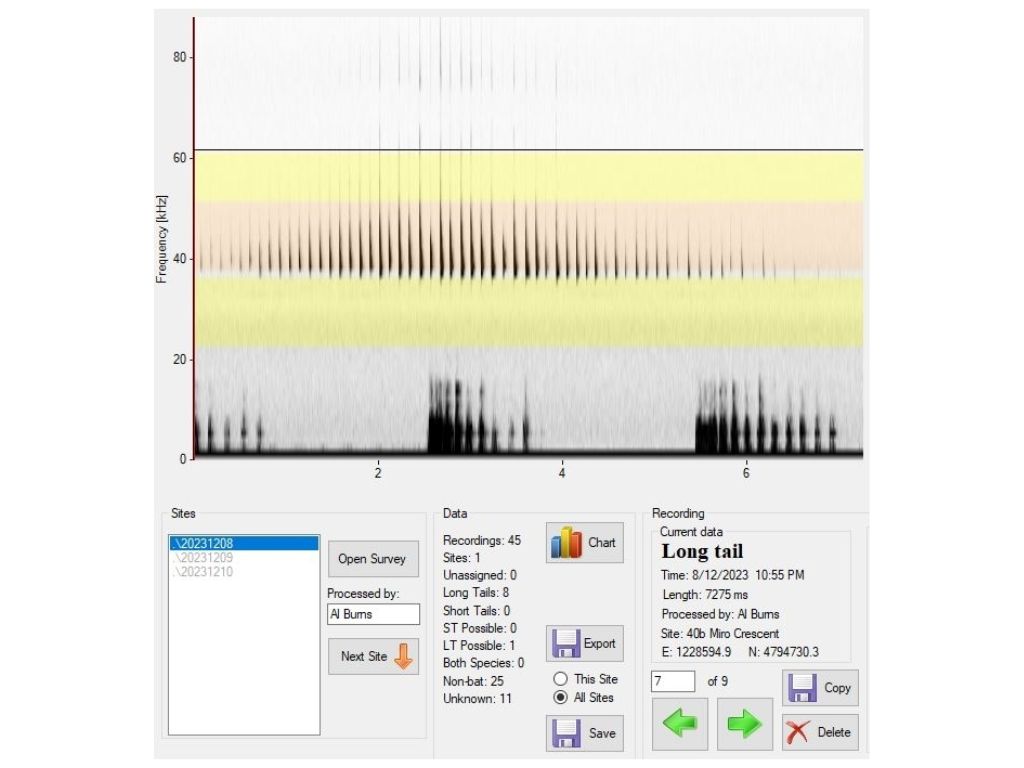

If bats are around, the high-frequency microphones will pick up their calls. The recordings show their calls visually.

“If you put it too close to water or it’s windy or raining, you get a distorted recording.

They also pick up the noise of rodents and bugs moving about in the forest,” Emma says.

The tiny sound pictures, or spectrograms, say more than just ‘a bat was here’.

Emma says that if you study and learn to read the pictures, you can tell when a bat is feeding, searching for others, approaching a bug, or socialising.

Real-time echoes: hand-held detectors

Handheld bat detectors amplify bats’ ultrasonic calls, converting them into sounds humans can hear in real time.

Armed with these devices and a thermal scope, Emma ventures into the bush to spot bats as they zoom past out of the forest.

“We head out just before dusk to try and see where they emerge from, trying a few different spots.”

When the handheld recorders come alive with frantic, shrill sounds, Emma will grab the scope to glimpse the bats flying around the treetops.

“We return at three or four am, hoping to catch them returning to the roost at dawn,” she says, though it’s tricky because long-tailed bats shift roosts almost every night.

This monitoring often involves long hours in the dark, listening intently. Sometimes, she emerges with only a few shaky thermal videos and dark circles under her eyes.

But Emma wouldn’t have it any other way. “I love bats.”

Monitoring bat populations and behaviours directly influences land management strategies. Discovering an area where an active roost may be, allows Ecoworks to target specific areas for predator control, which is crucial since bats are vulnerable to predation by introduced species.

“I’ve seen bats emerging from artificial roosting boxes and seen them flying around from afar, but it wasn’t until I was up close I could see why they are so susceptible to predation,” Emma says.

Furry AA batteries with wings

Emma is working towards getting accredited to handle bats. On a recent bat surveillance trip, she finally got to hold one.

“It was like holding a warm, furry mouse with wings in your palm. They are really cute and so small.

“It wouldn’t take much for a cat, rat or stoat to grab one,” she says.

Indeed, it doesn’t take much for predators to send a bat population into decline. In 2010, a male tabby cat killed 102 short-tailed bats in a week before a DOC ranger apprehended it near Ohakune.

Emma joined a team led by bat ecologist Kay Griffiths in central Hawke’s Bay to learn more about a bat colony discovered in a farm shed roof.

The team used harp traps made of fine fishing nylon, which the bats fly against and slide gently into holding bags. The bats were fitted with tiny transmitters on their backs.

“These transmitters, which don’t hurt them and fall off within a couple of weeks, help us track the bats’ movements and ensure their roosts are protected,” Emma explains.

The bats are released back into the darkness, the transmitting backpack sending out a signal for their travels to be tracked, helping to grow our understanding of this elusive species.

Monitoring bats reveals the hidden world of New Zealand’s pekapeka, which are at risk of extinction if we don’t protect them. Emma’s work helps us understand these bats better and ensures we can keep them safe for the future.