A recent study has found high exposure rates of toxoplasmosis in a kiwi population that does not share its habitat with cats.

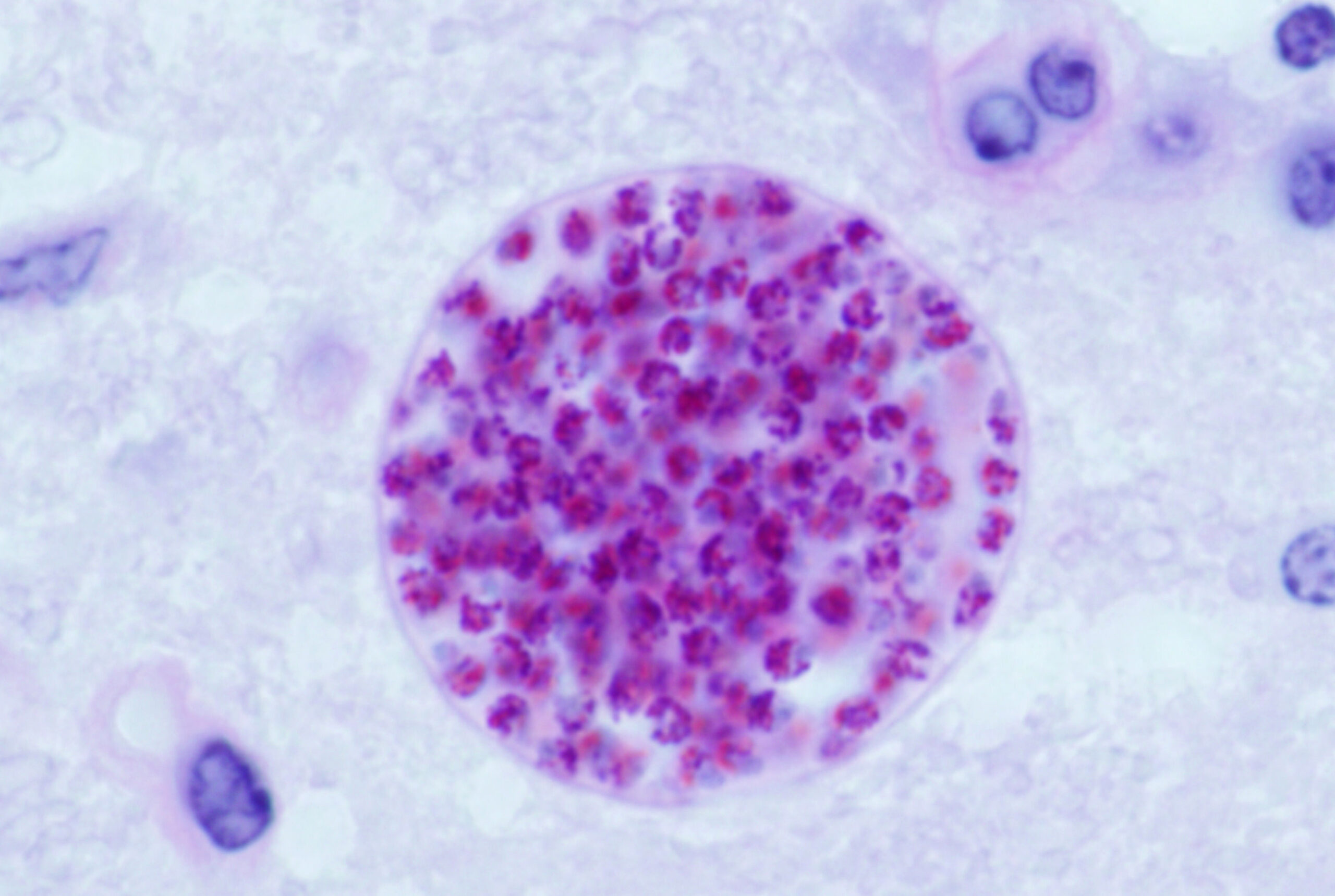

Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii or toxo), a parasite found primarily in cat poop, is a cause of sickness and even death in native wildlife. We’re talking kiwi, kākā, kererū and even Māui and Hector’s dolphins – all can become infected by this parasitic microorganism.

When toxoplasmosis was suspected in two sick little spotted kiwi living in Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne, researchers swung into action. They found 84.2% of tested kiwi inside the predator-proof sanctuary showed evidence of exposure to T. gondii.

Infection occurs from ingesting toxo oocysts found in food or water that felines faeces has contaminated. NZ’s domestic and feral cat populations are definitive sources of infection.

It makes you think twice about letting your cat poop in the backyard or flushing cat poo down the toilet (for the record, the best way to dispose of cat poo is in the rubbish bin).

Investigating an unseen threat

The sick kiwi were found during the day in poor body condition, displaying impaired coordination and weakness inside the fenced predator-proof sanctuary in Wellington.

Veterinary professionals provided intensive supportive care, but unfortunately, neither bird fully recovered. While the vets were unable to confirm the cause of the illness, the clues pointed to toxoplasmosis.

To define the extent of the infection inside the sanctuary, Department of Conservation researchers worked with Zealandia staff to sample 19 little spotted kiwi in January 2021. Blood samples were taken from their metatarsal vein, and both serologic and PCR testing were conducted.

Overall, 16/19 samples tested positive by either PCR, LAT, or both, resulting in an estimated prevalence of exposure to T. gondii of 84.2%.

Widespread exposure

The study reports: “Our results suggest that LSK [little spotted kiwi] at Zealand Te Māra a Tāne are widely exposed to T. gondii.”

It’s not unexpected that ground feeders such as kiwi are at high risk of exposure to T. gondii, but the route of exposure for the kiwi surveyed in the study is unknown.

“Cats have been excluded from the sanctuary since 1999 with the predator-proof fence. Oocysts survive in the environment for a maximum of 18 months in ideal conditions.”

Potential sources of infection for the kiwi include waterborne transmission through urban runoff from neighbouring land, windborne transmission, or ingestion of invertebrates carrying oocysts.

“In contrast to predator-free sanctuaries such as Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne, many populations of kiwi share habitat with cats, and these populations likely will have equal or higher levels of exposure to T. gondii.”

The study’s findings emphasise that disease should not be overlooked as a risk to kiwi populations, even in predator free sanctuaries such as Zealandia Te Māra a Tāne.

The potential effect of toxo in wild and captive kiwi is yet to be fully understood, and the study recommends further research in this field.

The complete study, authored by Harry S. Taylor, Laryssa Howe, Charlotte F. Bolwell, Kerri J. Morgan, Baukje Lenting, and Kate McInnes is published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases, is available publicly online.