Many of New Zealand’s native wildlife species are not only unique, they’re downright weird. Take our singing short-tailed bats for example. Auckland University researchers Cory Toth et al have been studying their behaviour and have confirmed that they’re lek breeders.

Like the kakapo parrot, male short-tailed bats sing to attract females who choose a mate based on the quality of his display.

It’s a rare type of courtship usually found in birds and our short-tailed bats are one of only two bat species in the world known to court this way. The male bats defend their singing roosts – but some roosts were found to be shared by several males who took turns to use the it. The courtship roosts were located near day-time roosts used by females, so that males had a greater chance of their lovesongs being heard.

The full article is published in Behavioral Ecology and is freely available. Females as mobile resources: communal roosts promote the adoption of lek breeding in a temperate bat (2015)

And for a lighter look at short-tailed bat courtship behaviour, check out Cory Toth’s video on YouTube.

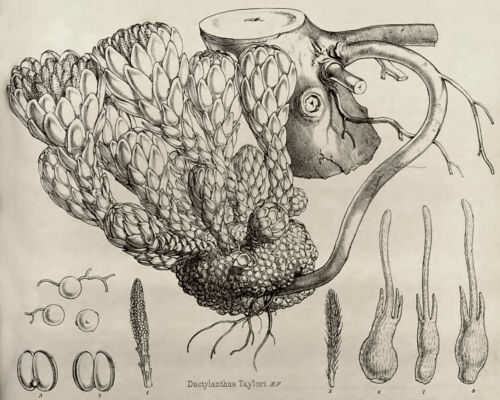

Their courtship isn’t the only thing that’s strange about our short-tailed bats. They’re also key pollinators of an equally strange and endangered parasitic plant – the wood rose. Short-tailed bats are New Zealand’s only native mammalian pollinator and the only fully temperate bat pollinator in the world. Because of their rarity, however, not to mention the difficulty in observing these small mammals in a forest in the dark, their contribution as pollinators has been little studied. Do other native plants depend on bats for pollination? Do they compete for the bats’ attention?

One recent study, again by Auckland University researchers, looked at pollen samples found on short-tailed bats and found that: “the amount and type of pollen carried by the bats varied temporally, with one pollen type dominating samples at any given time. The two plants most consistently observed in the pollen samples flowered sequentially with little temporal overlap, suggesting that their flowering phenology may be adapted to minimize competition for the pollination services of the short-tailed bat.”

The full article is published in the Journal of Zoology. The abstract is freely available and the full article can be rented or purchased: Competition for pollination by the lesser short-tailed bat and its influence on the flowering phenology of some New Zealand endemics (2014)

More about short-tailed bats – and more strangeness. Although they can fly, they spend much of their time foraging on the ground, not unlike mice. Small forest-dwelling bats living in cold temperate climates often have large home range sizes – but does this apply to a bat that scrambles on the forest floor?

University of Otago and DOC scientists Jennifer Christie and Colin O’Donnell checked out the southern sub-species of short-tailed bats living in the Eglinton Valley, Fiordland. They radio-tagged 23 bats during late summer and early autumn and followed their movements for approximately a week. Christie and O’Donnell found that collectively, the 21 bats for which they retrieved data ranged over an area of 14,710 ha.

“Thirteen colonial roosts were located within a central roosting area occupying 17 ha. A further 10 solitary roosts were located within individual foraging areas. Individual 100% minimum convex polygons varied considerably in size from 127.3 to 6,223.4 ha (median = 478.5 ha) with a range length of 2.2–23.0 km (median = 5.0 km).”

Within this larger area, there were small core areas where the bats concentrated 85% of their activity. Overall, however, the researchers concluded that: “M. tuberculata have relatively large home ranges, similar to many other small temperate rainforest bats, and implies that conservation areas designed for M. tuberculata should be large. Our predictions should be tested on populations of this species in areas with more abundant resources and milder climates.”

The abstract is freely available and the full article can be purchased: Large Home Range Size in the Ground Foraging Bat, Mystacina tuberculata, in Cold Temperate Rainforest, New Zealand (2014)

Finally a cautionary tale from a population of short-tailed bats living in Pureora Forest Park in the Waikato, where diphacinone – a first generation anticoagulant poison – was used in a rodent-control operation in the summer of 2008-2009.

Bats are not rodents, although they may look superficially like them. Short-tailed bats are, however, a small mammal which, like rats and mice, spend a lot of their time foraging on the forest floor.

Gillian Dennis and Brett Gartrell from Massey University’s Wildbase, Institute of Veterinary, Animal and Biomedical Sciences, report in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases on the deaths of 115 lesser short-tailed bat deaths between 9 January and 6 February 2009, and say that “it is likely that many deaths were undetected”.

“Adult bats showed gross and histologic hemorrhages consistent with coagulopathy, and diphacinone residues were confirmed in 10 of 12 liver samples tested. The cause of mortality of pups was diagnosed as a combination of the effects of diphacinone toxicity, exposure, and starvation.”

Milk samples were extracted from the stomachs of the dead pups and diphacinone was detected in two of 11 milk samples.

“Eight adults and 20 pups were moribund when found. Two adults and five pups survived to admission to a veterinary hospital. Three pups responded to treatment and were released at the roost site on 17 March 2009.”

It was not known whether the adults consumed the toxic bait directly or were poisoned through secondary consumption of poisoned arthropod prey. The authors conclude that: “the omnivorous diet and terrestrial feeding habits of lesser short-tailed bats make them susceptible to poisoning with the bait matrix and the method of bait delivery used. We recommend the use of alternative vertebrate pesticides, bait matrices, and delivery methods in bat habitat.”

The abstract is freely available and the full article in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases is available for purchase: Nontarget Mortality of New Zealand Lesser Short-Tailed Bats (Mystacina Tuberculata) Caused by Diphacinone (2015)