City dwellers and urban lizard gardens could play a significant role in future skink and gecko conservation in New Zealand, according to research just published in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning. Turning part of your garden into some desirable reptile real estate could really make a difference.

Researchers Christopher Woolley, Stephen Hartley, Rod Hitchmough, John Innes, Yolanda van Heezik, Doborah Wilson and Nicola Nelson carried out a scientific review of past, present and possible future lizard populations in New Zealand cities and found that 38% of New Zealand’s lizard species once had distributions that included our largest cities. For their land area, cities still support a disproportionately high number of species.

Of the species whose ranges once included cities, only 40% are currently still found there. Many of those species have a conservation status of ‘at risk’. Not only can we make our cities safer and better suited to these 40%, but some of that other 60% could possibly be reintroduced back again, if the right conditions can be created and maintained for them.

“Internationally, lizards are a common feature of urban biodiversity, but in New Zealand where many species are threatened, little is known about populations of native skinks and geckos in cities. Yet cities may offer unique opportunities for lizard conservation compared with alternatively modified habitats.”

The researchers believe that individual citizens can make significant contributions to biodiversity conservation, both by mitigating the negative environmental effects of urban processes and enhancing green spaces in cities to make them habitable for wildlife.

“Over the last two decades, a number of new initiatives have seen dramatic changes in the fauna of some cities. These include predator-free sanctuaries, community restoration groups and backyard pest trapping. Additionally, several city councils have adopted biodiversity strategies supporting these initiatives and encouraging public involvement. With this developing interest in urban biodiversity, it is an opportune time to evaluate the potential for faunal restorations in cities.”

The three largest cities in each of New Zealand’s two main islands (Auckland, Hamilton, Wellington; Nelson, Christchurch, Dunedin), were selected for the study.

“This selection provided representatives that varied in latitude, human population size and density, disturbance history and included both coastal and inland cities. The six urban cores were then described in terms of their total area, location, and types and proportions of land cover they encompass.”

Eight general classes of land cover type were used in the assessment: exotic grassland, exotic forest, exotic scrub, horticulture, indigenous forest, indigenous scrub, wetland and gravel.

“We collated knowledge about the current lizard faunas of six New Zealand cities and developed a list of species that would likely have been present in the locations of these cities prior to human settlement. Comparing the two, we found that, although each of the cities has at least one currently urban-dwelling species, the diversity of lizards in all of the cities has declined dramatically since human colonisation. Patterns of species loss in cities reflect those observed across New Zealand more generally; that is, the loss of large-bodied skinks and geckos, probably resulting from predation by introduced mammalian predators, as well as the loss of regionally endemic species.”

Large-bodied skinks and geckos are both an attractive meal for introduced mammal predators and are also less able to escape predation by hiding in inaccessible crevices as their smaller relatives can.

“While many of New Zealand’s lizard species are threatened, range-restricted or highly managed to ensure survival, others remain widespread and occur at varying densities in many cities. However, little is known about these urban populations, and anecdotal reports and studies at mainland sites suggest that many may be in slow decline.”

Individual lizards don’t really need a lot of space, making lizard-friendly urban gardens a useful conservation strategy.

“Many of New Zealand’s skink and gecko species have small home ranges (often less than 20 square metres), which allow them to exploit small patches of adequate habitat among the mosaic of environments found in cities, while being largely unaffected by nearby disturbance. Strong site fidelity can aid survival of urban-dwelling skinks.”

“In cities, strategies to manage lizard populations in the presence of introduced predators could be applied in natural areas such as bush reserves and wetlands, as well as modified environments like parks, backyards and informal greenspaces. Although untested, intensive, localised predator control and enhancement of habitat might be able to safeguard existing lizard populations in cities and potentially provide safe areas for future translocations.”

The high diversity of species that are currently, or were historically, present in the locations of New Zealand cities means that urban restoration involving recovery or reintroduction of populations could have significant benefits for lizard conservation. It could also help with lizard advocacy – raising the profile of skink and gecko conservation.

“Urban restoration of lizards may also serve to enhance the nature experience of urbanites and indirectly influence their perception of biodiversity in cities. Lizards are the only native non-avian vertebrate likely to occur in backyards and the fact that the home ranges of some animals may make use of habitat in just a single backyard makes some species excellent candidates for wildlife gardening.”

What’s more, when you get to know them, our lizards are a charismatic lot.

“New Zealand has a number of charismatic lizard species including one of the world’s largest geckos, Duvaucel’s gecko. Brightly coloured ‘green’ geckos of the genus Naultinus are commonly used as advocacy animals and still occur in and around some New Zealand cities. It is therefore conceivable that urban citizens might be motivated to undertake pro-conservation behaviours, such as incorporating native plant species into their gardens or maintaining predator control on their property, by the prospect of increasing the viability of their local gecko or skink population.”

It’s great news – but there are challenges too. There is so much we just don’t know about the lizards living just beyond our doorstep.

“There is a lack of knowledge about the ecology of the urban environment and how lizards might fit into this. Highly modified habitats and invasive predators are ubiquitous in most cities and their interaction with other environmental factors, such as temperature in particular, likely influences the degree to which they affect the fauna of a given city. For example, certain types of land cover and their position in a city may modify effects of introduced predators on populations. There is some evidence that complex cover, such as dense vegetation or rock piles, may reduce the detectability of prey or the hunting efficiency of predators”.

The authors looked at 4 specific questions in their review:

- What lizard species were present in the regions of six New Zealand cities prior to human colonisation?

- What is the current lizard fauna of each of these cities?

- How do the six cities differ in their land cover composition and other opportunities available to their lizard faunas, and

- What potential exists for restoration of lizards in New Zealand cities?

“The standardised method used to define urban cores created polygons that ranged in area from 52,186 ha (Auckland) to 5063 ha (Nelson). The percentage of this area occupied by urban land cover also varied widely among cities, with Auckland having the greatest percentage urban cover (87.3%) and Dunedin having the least (66.3%). The remaining land cover (non-urban land cover) was dominated by exotic grassland in all cities except Wellington where the largest non-urban cover type was indigenous scrub (61.2% of non-urban). The six cities fall between the latitudes of 36.84°S and 45.88°S and all are coastal except for Hamilton, the edge of which is approximately 40 km from the nearest coast.”

After analysing several species databases, including one with records dating back to 1837, and then refining their data, the researchers came up with a historic total of 19 species (5 geckos, 14 skinks) in Auckland, 17 (6 geckos and 11 skinks) in Hamilton, 16 (7 geckos and 9 skinks) in Wellington, 9 (5 geckos and 4 skinks) in Nelson, 6 (3 geckos and 3 skinks) in Christchurch and 7 (3 geckos and 4 skinks) in Dunedin.

“Sixteen out of the 43 (37.2%) currently recognised New Zealand gecko species and 24 out of the 61 (39.3%) skink species were determined to have a range that likely historically included one or more of the six cities. In all, eleven species of gecko and ten species of skink have been recorded within at least one of the six urban cores in the last 50 years.”

“The species identified as historically present in the regions of cities generally reflect a cross-section of New Zealand’s lizard fauna. The group also represents a wide variety of threat statuses, with 27 species currently classified as ‘at risk’ and eight classified as ‘threatened’. Restoration of the lizard faunas of cities could therefore not only offer excellent representation of national lizard diversity, but also have benefits for current lizard conservation at a species level.”

More than half (60%) of the species that historically occurred in the locations of the present cities have not been recorded in the last 20 years and have likely been lost from these areas.

“These species were, in many cases, the same as those that more generally suffered range contractions or extirpation on New Zealand’s mainland. Other species have remained on the mainland and still exist in populations just outside the urban fringe. The majority of species lost from cores (58%) were local endemics (those that historically existed in a single city).”

Smaller lizard species and those living in warmer climates, seem to have been more likely to survive in our urban centres.

“The two cities that have retained the highest proportion of their gecko fauna (Wellington and Auckland) also have the warmest winter temperatures (MetService, 2018).”

As well as the usual modern-day challenges of mammal predators and habitat loss, our city landscapes present some unique challenges to urban-dwelling lizards: traffic and related infrastructure, high densities of domestic cats, and high levels of maintenance of public and private green spaces (e.g., landscaping, lawn mowing, use of pesticides). Not all species are negatively affected, however. Some lizards have benefitted from change.

“Oligosoma polychroma, the most widespread and abundant skink in both Wellington and Nelson, is diurnal and an avid basker that inhabits native and exotic grassland habitats that have expanded in coverage since human settlement. This species also possibly benefits from highly modified open habitats in the urban environment as it is often seen basking on artificial surfaces such as wooden decking or asphalt.”

The researchers showed that 15% of New Zealand’s lizard species are currently found in six cities whose area represents around 0.4% of New Zealand’s land area, and that 38% of lizard species might have been found in these areas historically.

“Through restoration of these species in urban habitats, huge potential exists for lizard conservation. In addition to the conservation benefits of establishing new populations, translocation into public reserves could be a significant motivator for both volunteers and the wider community.”

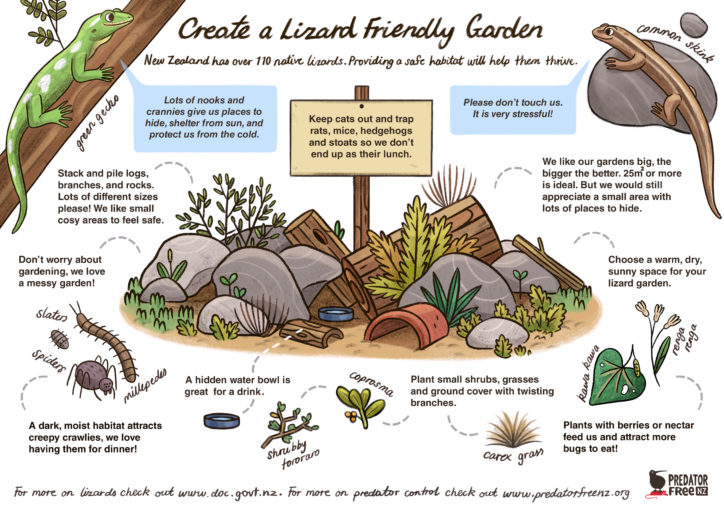

Formal green spaces such as public reserves make up only a fraction of a city’s total area. What about backyards? Maintaining a lizard garden doesn’t have to be hard labour – quite the opposite in fact. Lizards like things a little wild.

“Lizard gardening, the planting or construction of habitat to provide resources for lizards, is increasingly being encouraged in backyards. Nectar- and fruit-producing plants offering food resources, or dense shrubs and grasses that provide cover from predators are often used. A number of weedy, exotic species (e.g., Tradescantia fluminensis) are also thought to provide habitat for lizards, and one study found that garden untidiness correlates with skink occurrence, indicating that lizard gardening does not require intensive management.”

“Another burgeoning backyard initiative in New Zealand is community pest trapping where community groups in residential suburbs receive funding to buy or build traps for pest mammals, which are distributed by group members around their properties. In Wellington, 27 suburbs have their own group, with up to 5526 traps deployed across the city. Due to the large contribution of domestic gardens to the urban green space, such initiatives in backyards could have significant benefits for wildlife populations.”

But what happens when a lizard-loving owner moves house?

“One limitation of privately-owned gardens, however, is that unlike public spaces the maintenance of habitat is at the discretion of the current owner and there is always a risk of garden destruction when ownership changes. One way to ensure greater longevity might be to encourage the use of covenants, currently used on natural areas on privately-owned land, on small residential sites.”

With lizards only needing a small home range, even areas like planted road strips offer possibilities.

“Other informal green spaces such as planted strips alongside roads and around the perimeter of playing fields currently provide habitat for lizards in cities and modifying these to make them more lizard-friendly might increase the available habitable space in cities. Modifications could involve predator control, increasing cover using rocks or plantings, altering maintenance regimes, and halting the use of glyphosate sprays”

The researchers believe that one of the biggest challenges for managing native lizards in cities is the lack of knowledge about the current state of populations.

“Future research is needed to create a baseline to assess lizard population trends in cities and assess the value of different kinds of urban habitats for supporting lizard populations. In the highly heterogeneous environments of cities, where populations are likely fragmented and suitable habitat is patchy, citizen science might be a useful tool for gathering distribution data.”

Overall, they conclude their review with hope for a more lizard-friendly urban future.

“Native lizards are an important component of New Zealand’s urban biodiversity. Despite the six major cities in this review having lost significant proportions of their original lizard fauna, a wide variety of habitats in cities still support numerous species. The current climate of urban restoration and promotion of biophilic cities in New Zealand promises to improve the prospects of wildlife in cities.”

“In future, cities may offer opportunities to conserve a larger proportion of endemic species by reintroducing species that have become regionally extinct. Additional to direct conservation benefits to species, supporting urban lizards provides an opportunity to engage the public, especially through some of the large, charismatic species that are native to many of the cities’ regions.”

The full review is published in the December 2019 volume of Landscape and Urban Planning. Only the abstract is freely available online but author contact details are supplied.

Reviewing the past, present and potential lizard faunas of New Zealand cities (2019)